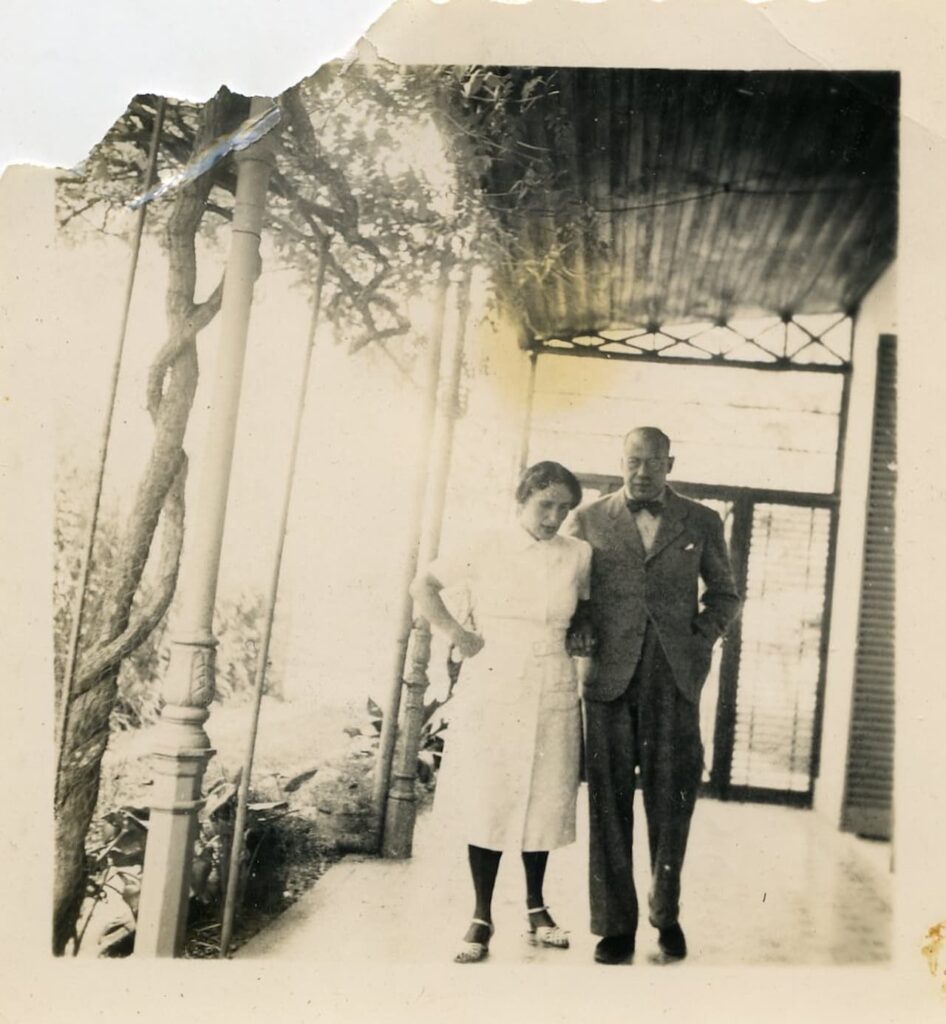

Fritz and Mimi Ellmann never fully adapted to Argentina. Materially, they led a comfortable life (not quite as grandiose as it had been in Vienna, but still much better than what the Simkos endured in La Paz and later, when they arrived in Buenos Aires). After their initial stay with Lilly and Hugo Schwarz, they lived in the Calle Nueva York 4563, then in the Calle Pareja 3690, both in Villa Devoto, Buenos Aires (with Fritz’s car), in houses that were smaller and less fancy than the Glanzinggase in Pötzleinsdorf, but included small gardens. Almost from the outset, Fritz had access to a car.

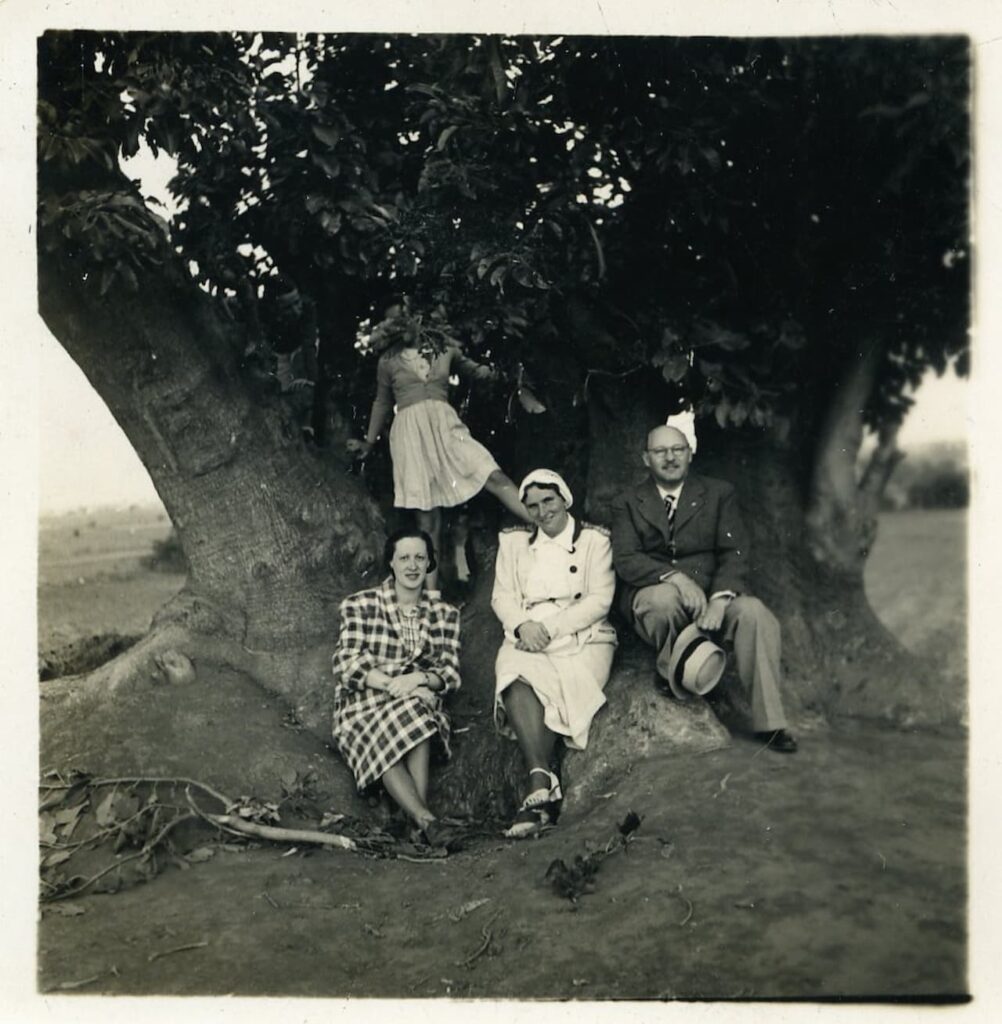

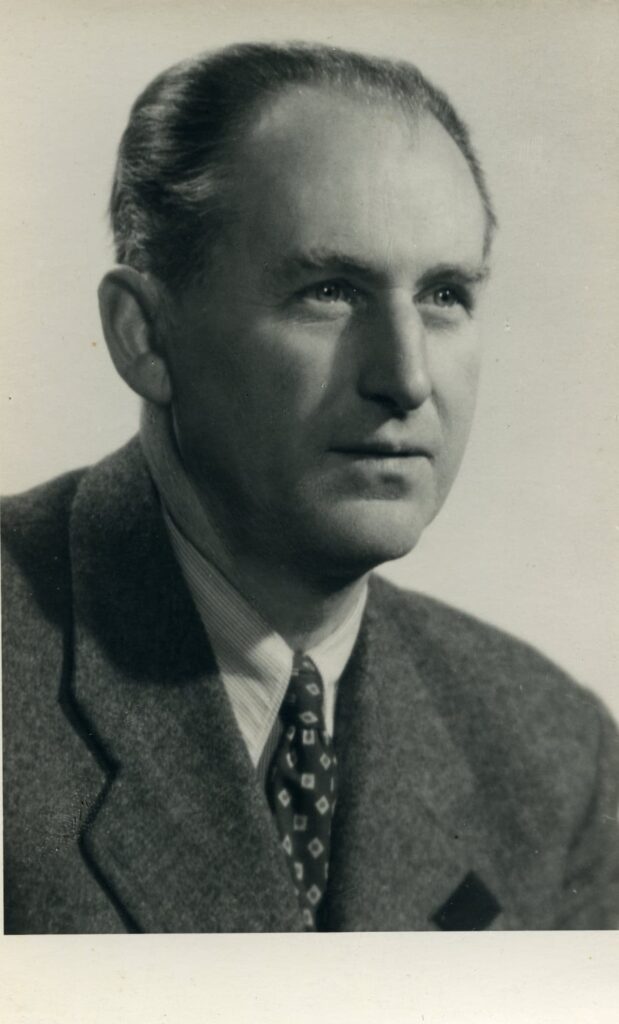

Until his retirement at the end of the 1950s, he worked for the Avenburg brothers, Jewish immigrants from Odessa. As their manager, he developed a whole range of metallurgical precision instruments, centred around a large variety of locks. The first can opener manufactured in Argentina, was invented by Fritz, with the assistance of my uncle Heinz, who would himself become an engineer. Fritz was appreciated and developed close ties with one of the owners, David Avenburg and his family, with whom frequent picnics were organised, often in the wide-open spaces beside the newly constructed Avenida General Paz.

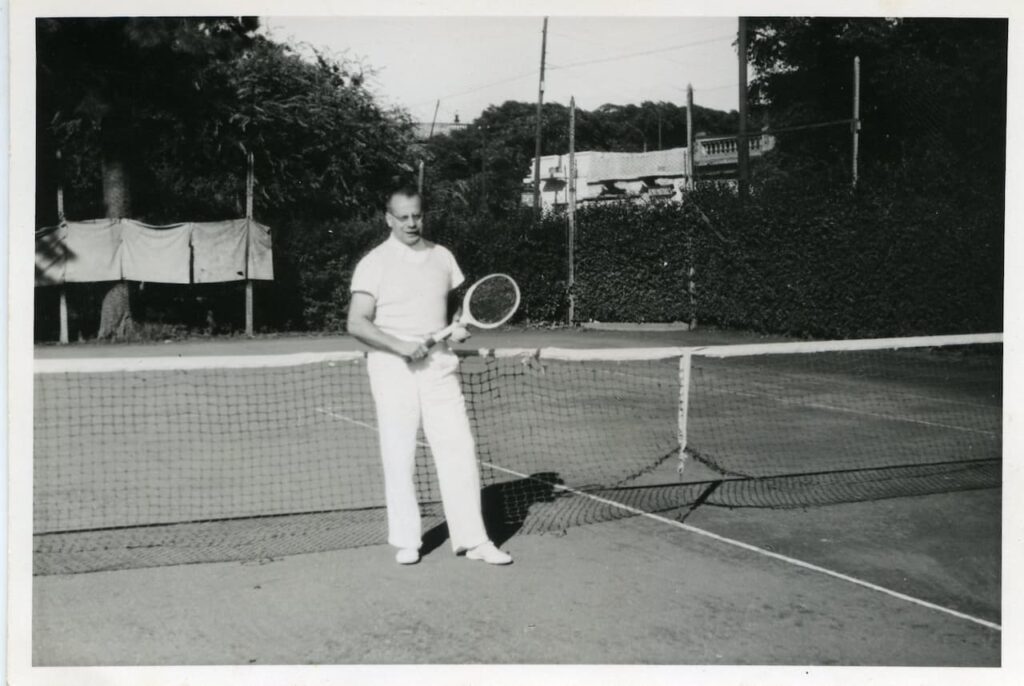

Fritz also was a co-founder of the Villa Devoto Tennis Club, which still exists, situated a few minutes’ walk from his home. He worked what was necessary, but not more. His real passion was reading and he was lucky enough that the container including the 6,000 books he transported from Vienna to Buenos Aires actually arrived. There was a second container, which got inexplicably lost and only appeared in Argentina after the war. When the Ellmanns finally accessed it, it had been so badly damaged that most of its contents had to be discarded.

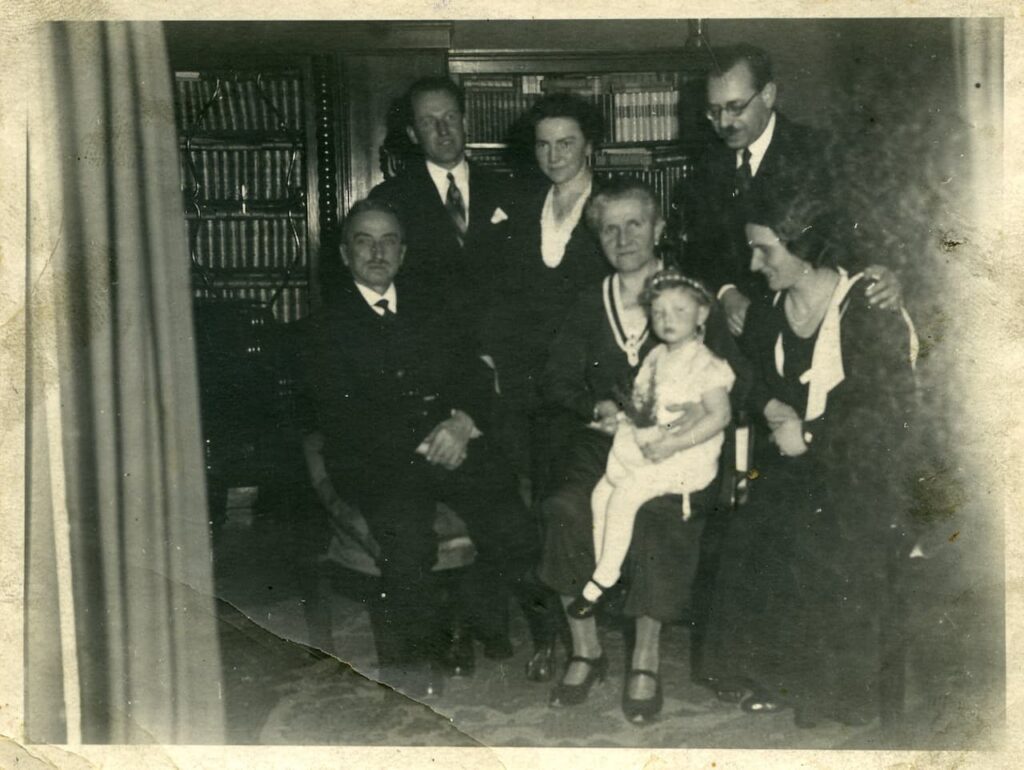

Fritz, like my great-grandfather Wilhelm, was stingy. Wherever he could, he saved money. His major expenses were for insurance (I guess that the trauma of the emigration marked him sufficiently to want to be insured against everything) and for books. He was an early bird and would frequently be found locked up in his huge library at 5 or 6am, reading and re-reading his books, before going off to work at about 7.30am. He became the best client of the only antiquarian in Buenos Aires who stocked German language books. Many of these books are now with me in Geneva.

The love for books and reading is something I inherited from Fritz. I often catch myself hoping that the next weekend will be rainy, which will allow me to sit quietly in a corner and read a book. Bookstores, virtual or walk-in, are my great addiction. Whichever city I am in, if a bookstore comes into view, that’s where you’ll find me.

There is no record of Fritz and Mimi playing concerts together for their guests in Buenos Aires, as they had so regularly done in Vienna, but Fritz twice a month gave lectures in his home about subjects related to philosophy, the social sciences and great writers. These lectures fascinated my Dad, who found in the Ellmanns (and in Fritz particularly) a dose of culture which had escaped him during the years of emigration.

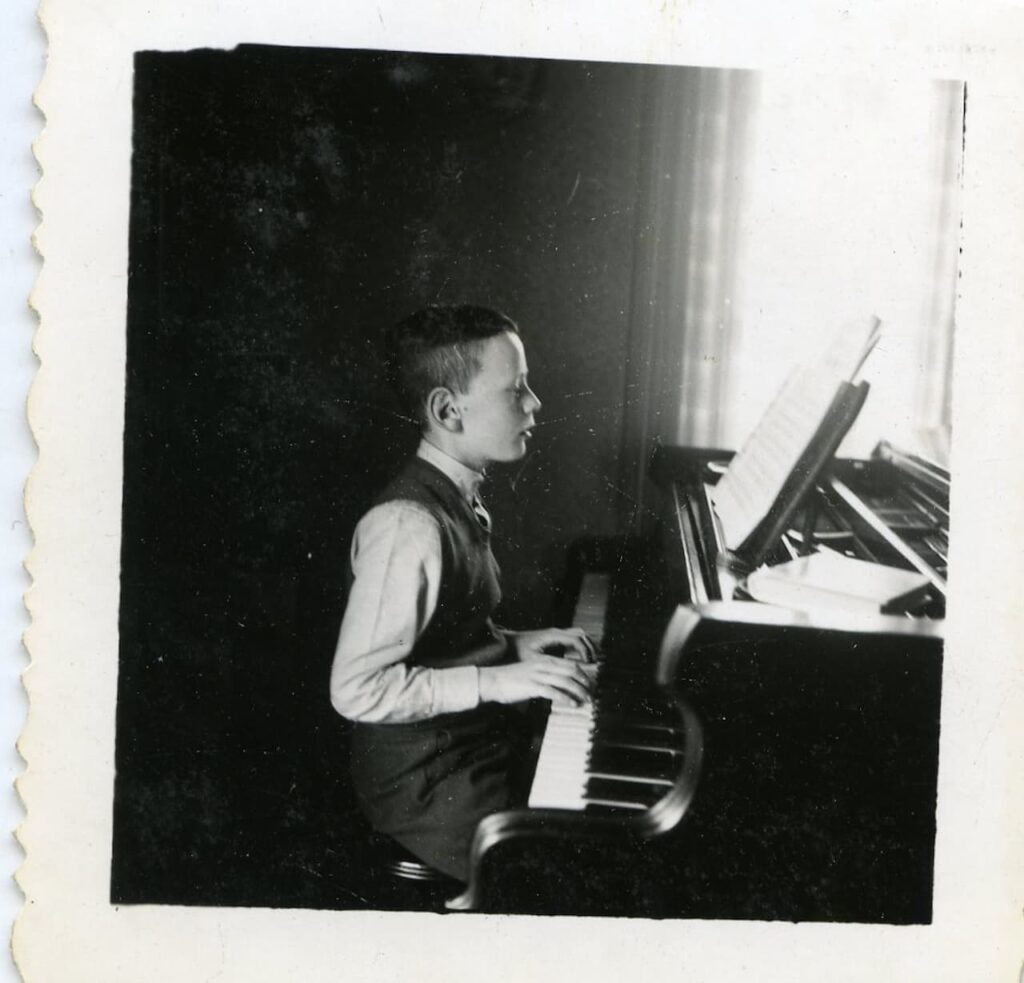

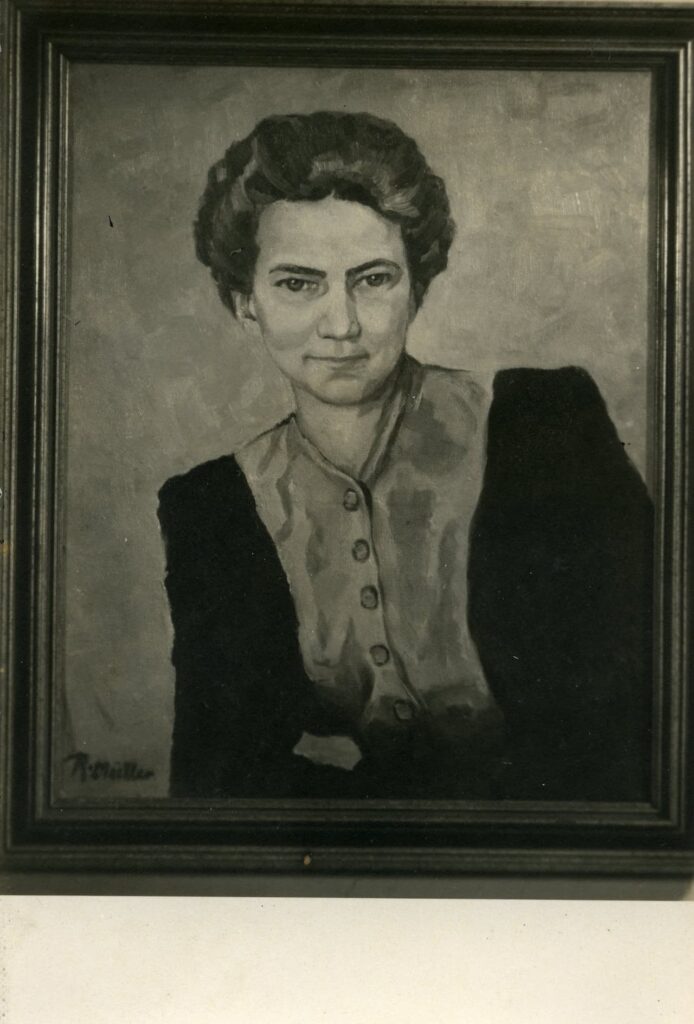

Unlike my father, who embraced South America and Argentina specifically, seeing it as his new home, Fritz and Mimi saw themselves as Europeans who necessity had driven to the other side of the world. They learned Spanish to get by, but never really mastered the language. Their cultural ties stayed firmly anchored in Vienna—the people they met, the issues they discussed, the food they ate, their way of life—it all remained very Austrian. Mimi did what she could to put on a brave face and in many ways she succeeded. By all accounts, the Ellmann’s home was filled with a warm atmosphere, where people were welcomed by a loving, attentive and caring Mimi who, despite the monetary constraints imposed by Fritz, regularly concocted masterful Viennese meals. This was often followed by my grandmother playing the piano and singing Viennese songs or famous arias from well-known operas.

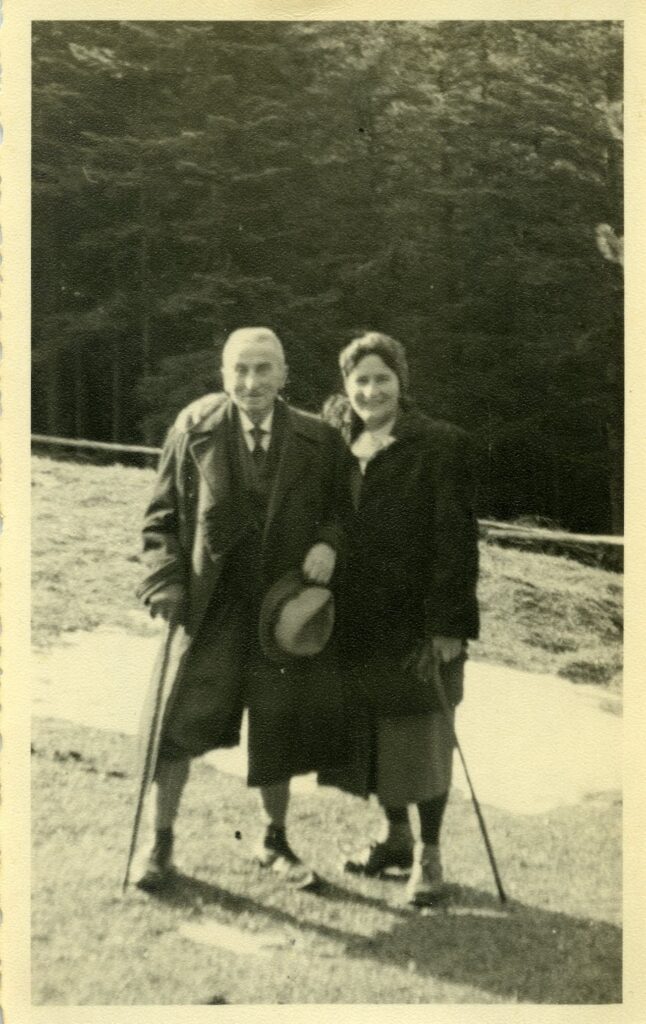

Fritz never returned to Vienna, but Mimi did travel back once, in 1947. She had been longing to see her father and the city she had grown up in. Her mother had died during the war, and her sister Paula immediately after the war ended, at the age of 47. This had affected her deeply and may have led to her first stroke in 1945. Correspondence with Austria during the war years had been very difficult (letters arrived after several months’ delay and were always censored), so she had, in fact, very little information on how her father was.

My grandmother’s sister Paula had married Ludwig Ellmerich before WW2. He was, by all accounts, a good husband and they lived a happy life together. Ludwig had joined the Nazi Party early on, long before the Nazis invaded Austria. Like many of his countrymen at the time, he thought that the Austrian state was too small to be economically viable and that joining Germany would be advantageous. Like many Austrians, he also admired the way in which Hitler had brought security and prosperity to Germany. Ludwig, like my grandfather Szigo, thought that Hitler’s anti-Semitism was primarily a propaganda tool, and that once in power the Nazis would tone down their hatred of the Jews. He did, however, notice that in many areas of Viennese life, Jews were occupying the main positions. He had intended to enter university, but had not been accepted. When he went through the list of those who had, he noticed that the vast majority were Jews. This made him think that perhaps Hitler (who had himself been denied entry to the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna) had a valid point when he clamoured that the Jews had unjustly monopolised higher education in Austria, as well as many branches of commerce.

Ludwig supported the Nazis even during the brief time when the party was declared illegal in the 1930s, but was indeed horrified by the way they behaved after Austria’s annexation to Germany in 1938. He helped Fritz during the difficult time after Austria became a part of Germany, and took care of what was left of Fritz’s property until after the war.

After my great aunt Paula died, Ludwig remarried. He, and especially his second wife Lene, stayed close to our family for the rest of their lives. Lene, who was much younger than Ludwig, and died only in the late 1980s, was a frequent visitor to our home in Argentina, and we always spent time with her when we visited Austria.

My father’s experience with Ludwig had a strong impact on my understanding of ‘good’ and ‘evil’. I realised at an early age, that not all Nazis were criminals or bad people, and I began to see why perfectly sensible and decent individuals, like Ludwig, could have been attracted to Hitler’s party. This was the start of my fascination with Nazism, and by extension, to other extremist political movements, like Republicanism under Donald Trump, which from the outside looked evil, but attracted to their ranks many rational and sensible people (like my father).

Mimi arrived in 1947 to a Vienna devastated by the war. She was shocked by what she saw—a city in ruins, widespread hunger and totally demoralised people, who had lost two world wars. Austria had been occupied by the Allied forces since 1945. Vienna was deeply in the Soviet occupation zone but, like Berlin, the city itself was administered by all four Allied forces. Wilhelm’s home at the Keplerplatz, which had been badly damaged by bombs, was in one of the zones occupied by the Soviets.

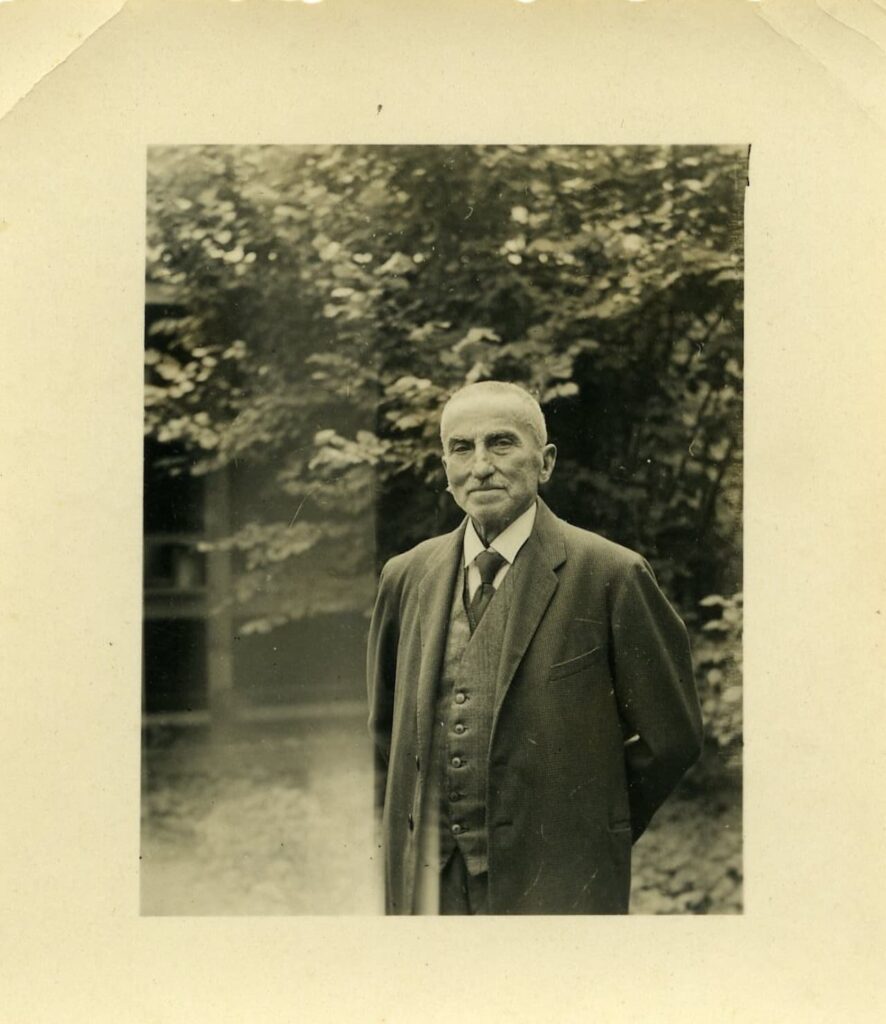

Nevertheless, it was a happy moment for Mimi to again see her ageing father, who would die shortly afterwards, at the age of 80.

Mimi never fully recovered from the shock of her trip to Vienna and died in Buenos Aires shortly afterwards, in 1951, at the age of only 50. She was sorely missed and especially my mother Lisl remained disconsolate for a very long time, arguably for the rest of her life. Paul says that there was a Lisl ‘pre-Mimi’ and another one ‘post-Mimi’. Annie, Fritz’s second wife, would only partially fill the void that Mimi left in Lisl’s heart.

The Simkos arrived in Buenos Aires in 1946. Szigo had met the Argentinian Consul to Bolivia while waiting on him at the Sucre Palace Hotel, and charmed him into issuing a safe conduct to Lilly and Paul, ‘so they can visit their family in Buenos Aires’. A safe conduct was necessary because at the time the Simkos were considered stateless: their German passport, with which they had arrived in Bolivia in 1939 was not valid because Austria in 1946 was no longer considered by the international community as belonging to Germany, while at the time Austria itself did not yet fully exist as an independent country.

The Argentinian Consul obliged, but as a safety precaution to ensure that the Simkos would return to Bolivia, the safe conduct excluded Szigo, who was left behind as a hostage.

However, it had been clear from the start that Lilly, Paul and Szigo would never return to Bolivia. Lilly’s sister Rosl had told them that if they succeeded in getting to Argentina, ‘the rest will be fixed here’. And so it happened. Rosl’s second husband Paul Wachsmann, who she had met and married in Buenos Aires after her first husband had passed away, was a wealthy and well-connected man. He arranged for a permanent residence status for my father and his parents with the help of the local head of the police department, with whom he was ‘on very amicable terms’.

Szigo arrived in Buenos Aires almost at the same time as Paul and Lilly. He took the train from La Paz to Villazón, a small town on the border to Argentina. There he hired a local guide who helped him walk across the border to La Quiaca on the Argentinian side. From there, he just took a train to Buenos Aires.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko