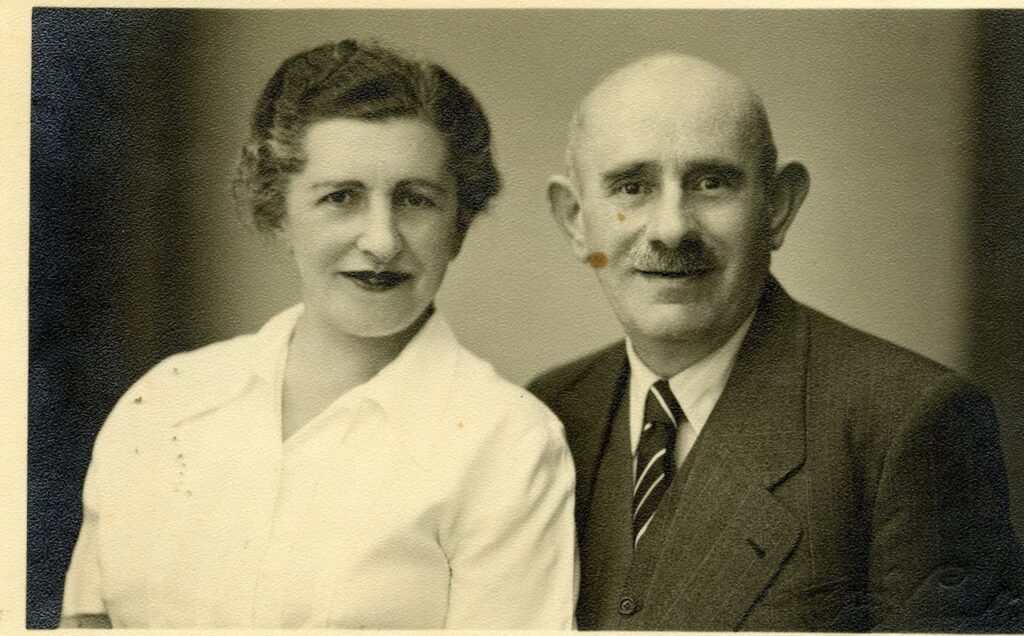

Szigo’s parents stayed in Vienna. His father Josef would die shortly afterwards of a natural death, but Regina died in the Theresienstadt concentration camp in 1943 or 1944.

In order to extract the last of their savings and give elderly Jews a false sense of security, the Nazis advertised Theresienstadt as a ‘spa town’ where elderly Jews could retire. They encouraged them to sign Heimeinkaufsverträge, fraudulent home purchase contracts, with the promise that they would be living in individual rooms in a ‘retirement home’, and that they would be cared for by nurses. Those who didn’t cooperate were told that they would be deported to ‘the East’.

In fact, the conditions in Theresienstadt were abysmal and most of the elderly died from disease or malnutrition almost immediately after arrival. Those who didn’t, were deported to Ausschwitz and other extermination camps.

Under pressure from the Czech government in exile, as well as Danish and Jewish organisations, the Red Cross visited Theresienstadt in June 1944. In preparation for this visit, the Nazis cleaned up the place, and dressed and fed the inmates properly. No one, under the threat of death, was allowed to speak to the visitors, with the exception of a small, pre-determined group, who were forced to deliver previously arranged messages. The visitors from the Red Cross, who spent eight hours in Theresienstadt, had to strictly follow a pre-determined path, where the inmates were shown working in the fields or playing football. The visitors also attended the production of the opera Brundibár, performed by a group of children. After their visit, the Red Cross delegation reported that ‘all is well’ at Theresienstadt and that their investigation showed that no one was deported from there. Food was plentiful and the inmates lived a good life, the report said.

To further profit from the ‘clean-up’ of Theresienstadt for the arrival of the Red Cross, as well as to quell mounting rumours of death camps, in the days after the delegation visited, the Nazis shot a film called ‘The Führer offers a city to the Jews’.

It’s unclear how long and under which conditions Regina died in Theresienstadt, and whether she lived long enough to witness the short-lived ‘clean-up’, but my guess is that she died quickly upon arrival, as most elderly Jews did.

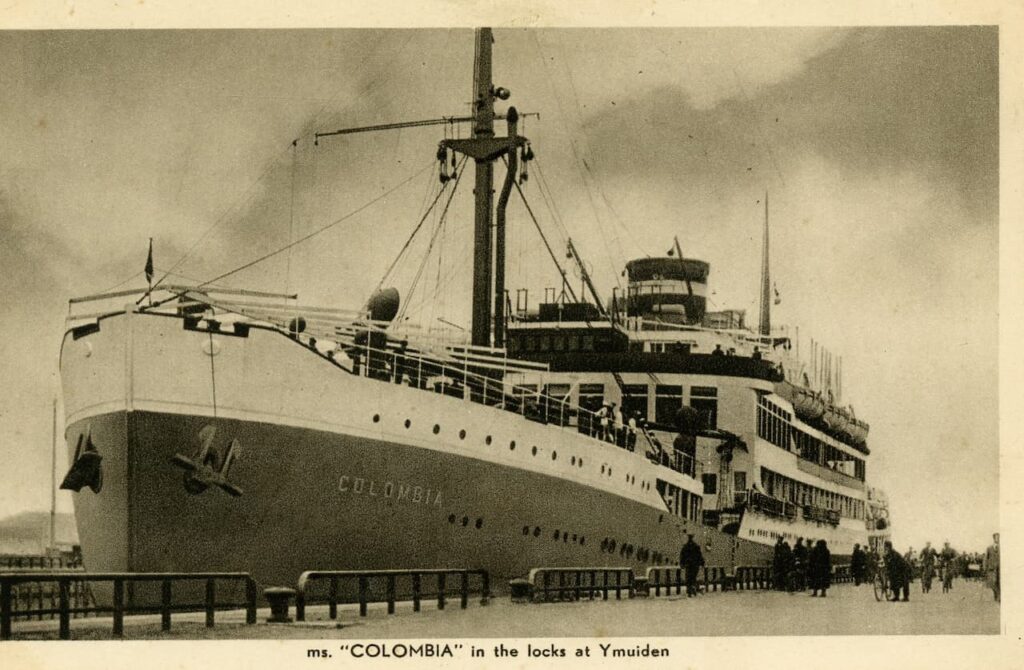

For my father, the experience of leaving Vienna and settling in Bolivia was a breath of fresh air. He had felt loved, but also strangled by the narrowness of the Viennese and of course by the increasing restrictions that the Nazis imposed on Jews. A lively, curious and charming child, Paul used the lengthy ship ride from Amsterdam to Arica (Chile) via Panama City, on the steamer ‘Colombia’ to learn Spanish, make new friends and start to liberate himself from the oppressive protocols of his upbringing.

The Simkos led a very modest existence in La Paz, where they lived until 1946. All three lived in one room, which served as a bedroom, sitting room and included a small kitchen. There was one toilet at the bottom of the building— it serviced 40 rooms.

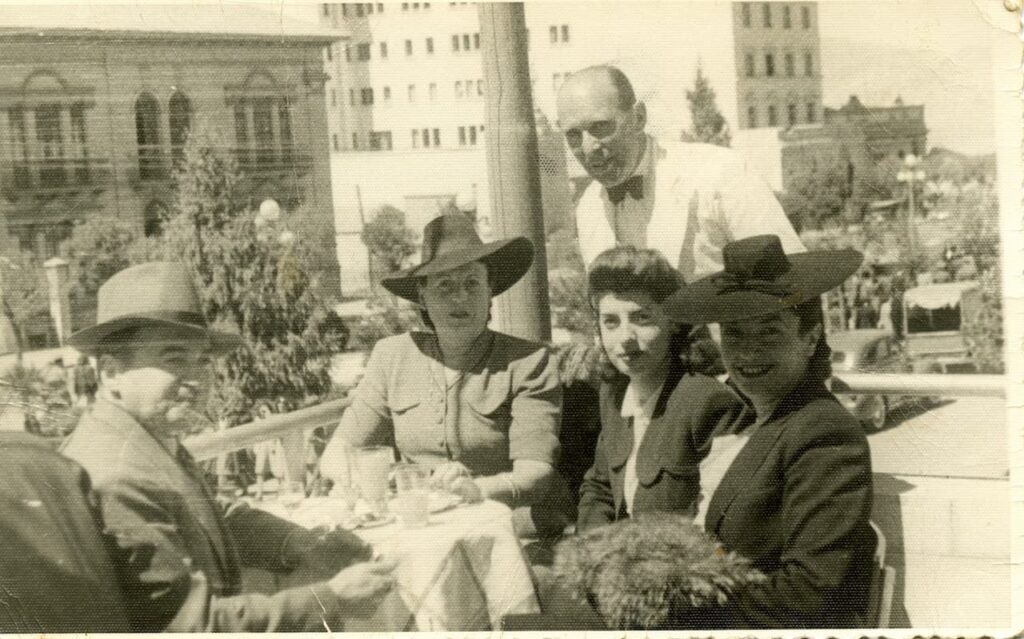

Szigo worked as a waiter at the Sucre Palace Hotel, the fanciest establishment in La Paz, situated on the fashionable Prado Street. He had no salary; his only income were tips. But it was enough to scrape a living and Szigo was by nature not a complainer. It was also a good place to make interesting contacts. It was on the terrace of the Sucre Palace that Szigo met the Argentinian Consul to Bolivia, which led to the obtention of an entry visa to Argentina for Paul and Lilly in 1946.

Lilly and Szigo quickly made friends with the local German-speaking group of immigrants and integrated well into the small, but active expat group in La Paz.

In the meantime, Paul, liberated from the cobwebs of Vienna, free from school (he only attended a few classes for a short period of time), rapidly got into business.

As a 13-year-old he started work for Leon Weil, a company that imported a large variety of products. He swept the floors, served coffee to the employees, sealed envelopes and distributed them by hand to the company’s clients (at the time there was no postal service in La Paz). But he was underpaid and felt so badly treated, that without telling his parents, he resigned after about a year. Fearful of his parents’ reaction, he left Leon Weil’s office and went to see Marc Rotstein, a man he had met while distributing Leon Weil’s post.

Rotstein, who called himself ‘Mr. McRedston’ liked to introduce himself as ‘the CEO of The Anglo-American Trading Corporation, with offices in Europe, Australia and the US’. In reality, Rotstein ran a one-man show, and the offices he indicated in his pompous letterhead were those of family and friends around the world. Rotstein sensed that the 14-year-old had potential, hired him on the spot, and offered him a much higher salary than Leon Weil, but on the understanding that Paul would be present in the shop whenever Rotstein was travelling (which was quite often).

Paul quickly realised that Rotstein was full of pretences, but one thing was true about his business: the cashmere fabrics he sold were indeed the best available in Bolivia at the time. He also realised that some customers, who wanted only the top of the range, were wealthy enough to pay more than the price Rotstein was asking for. After Paul suggested to his boss that higher prices could perhaps be obtained, the startled Rotstein proposed to Paul that on any sale beyond the indicated price, Paul could keep 20% of the additional income. Paul quickly began to earn serious money. Less than a year after joining Rotstein, he was making ten times more than at Leon Weil, and considerably more than his own father.

Szigo was not amused. He had agreed for Paul to leave school early because he wished his son to ‘learn a trade’. He had noticed that tailors, shoemakers and bookbinders were able to set up shop and earn a living as soon as they arrived in La Paz, whereas people like himself found it much harder.

So, he insisted on Paul leaving Marc Rotstein and obtained for him an apprentice job at Arno Hyman, a manufacturer of overalls for miners. Paul was miserable—not only was he not good at cutting fabrics, he was also badly treated by his boss. But soon his ability with clients was noticed by the owner, who placed him in the commercial department, where Paul, having learned to take risks while with Rotstein, suggested he was paid primarily on commission. Here again, he was successful and quickly started to earn much more than his father.

When Szigo found out that his son was once again not ‘learning a trade’, he found him a spot at Gutentag Hermanos, who imported fabrics from Argentina and transformed them into ready-to-wear garments in La Paz. The owners promised Szigo that young Paul would be taught marketable confectioning skills. Paul was indeed happier at Gutentag, but after a short while had mastered the technique needed and signalled that he had free time. The owners, enchanted by his energy and entrepreneurial spirit, put him in touch with clients. Here, as in his previous jobs, Paul excelled and quickly became the darling of the ladies coming to visit Gutentag’s premises. Again, he arranged for part of his salary to be paid on commission and did very well for himself. After a while, the owners hired someone else to do the manufacturing work and Paul was placed full time in the customer-facing commercial area. This time Szigo gave up and Paul stayed at Gutentag, earning enough to support the entire family, until the Simkos left for Buenos Aires in 1946.

Szigo was certainly well-meaning in his unsuccessful efforts to get my father to ‘learn a marketable trade’. In the process, however, he missed a key point: he focused on what he thought would be ‘a good trade’, without looking at what his son was actually best at. At the age of 14, Paul was not good at working with his hands, but he was clearly displaying the strengths that would make him so successful in future years: he was curious, intelligent, honest, trustworthy and very charming. He had a way with customers that instantly put them at ease. To this day, he has the extraordinary gift of using stories (most of them hilarious) to make a point. This creates a relaxed environment, so necessary and propitious for business success. On almost any occasion, and especially if a negotiation was difficult, Paul would say: ‘This reminds me of a story…’ and then rattle off what was invariably an amusing, but also insightful and instructive anecdote. This put everyone at ease and usually resulted in a positive outcome.

My father’s experience in his early years helped me approach my sons’ professional paths in a way that, I hope, has been more enlightened than that of my grandfather. Since they were very small, I tried to see where their true strengths lay, and encouraged them to seek a professional path that fulfilled them—regardless of what that path might look like. Only the future will tell if I succeeded!

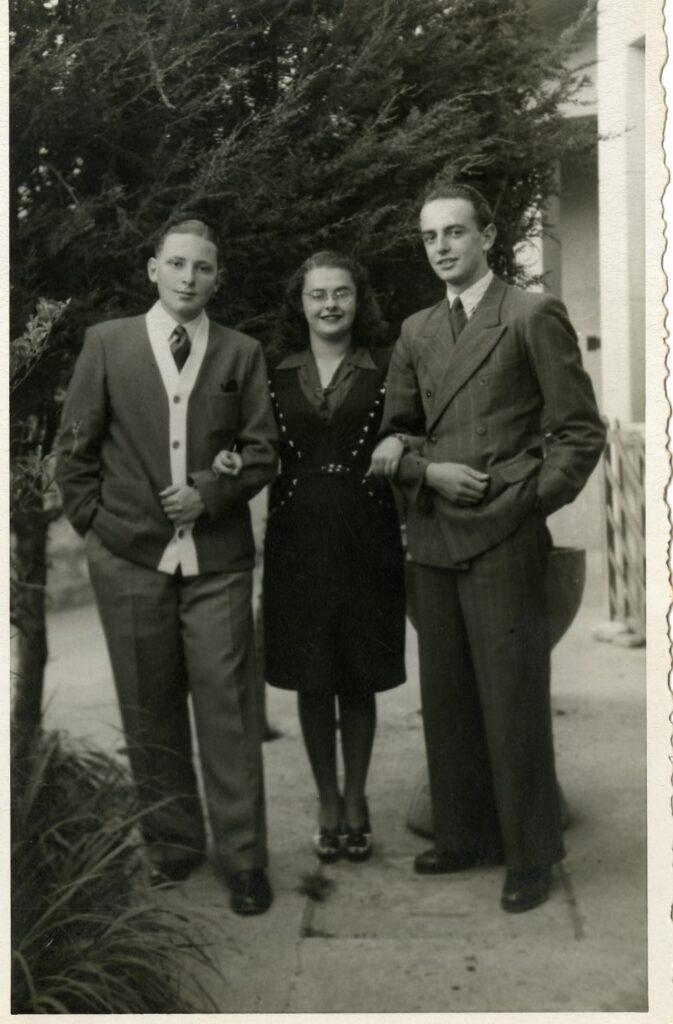

During his years in La Paz, Paul built what would become a lifelong group of friends through his association with the Boy Scouts. Every weekend and several evenings during the week, he would join his friends there. With them, he visited many areas of Bolivia, learned how to build tents and cook in the open air. But the Boy Scouts also instilled a sense of camaraderie in Paul and firmly implanted ethical values in him, which are to this day strong hallmarks of his personality.

Paul’s adherence to simple, but powerful values—unwavering honesty, hard work, loyalty, trustworthiness, kindness, support of others, are all principles that come from his time with the Boy Scouts in Bolivia, and that he transmitted to his children. His conviction that people are fundamentally good, and that if you treat others well, you will bring the best out of them, stem from his time in Bolivia. These are principles that my father didn’t just talk about, he lived them. I never once saw him lie or misrepresent anything. I frequently saw him lend a hand to anyone who needed his help.

Paul invariably trusted people. And he always believed what you said. He was not a perfect father, his opinions were often strong and unbending, but he was exemplary in his ethics. This created an atmosphere in our home that, although sometimes tense, was always underpinned by values that were incredibly healthy. They have led, among other things, to an extraordinary sense of trust and support among my brother, my sister and I, to a level that I have rarely seen in other families. We owe this, and much more, to Paul’s upbringing.

My father was well integrated and much liked in La Paz. More than one family would have wanted the charming, earnest and successful Paul to have married their daughter. One of those who had an eye on him were Mr. & Mrs. Schär, fellow Austrians who ran a small pension in La Paz, where Paul, Szigo and Lilly had stayed in the initial weeks after their arrival in La Paz. Liane Schär, about the same age as my father, signalled that she was attracted to him and her parents were delighted—they could see how Paul might just be the right son-in-law to lead the small pension into an even brighter future. But Paul, then as now a very practical man, looked at Frau Schär and thought: ‘If this is what Liane will look like when she’s older, then it’s not what I want’ and politely found his way out of the Schär entrapment.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko