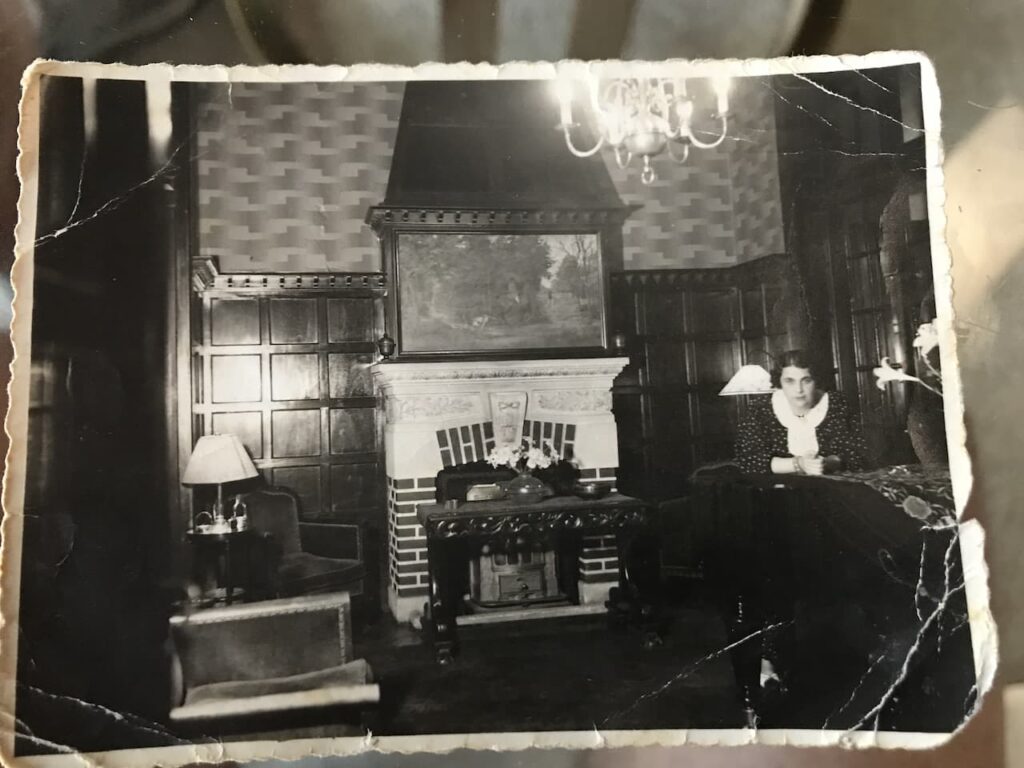

My great-aunt Rosl was born in Vienna in 1896. Like my grandmother Lilly, she had been brought up in a home that was nominally Jewish, but not religious. It was clear that the girls would marry Jews, but Rosl had sworn that she would never marry anyone called ‘Kohn’, a name she considered vulgar. But just after WW1, she met and fell in love with Gustav (Gusti) Kohn. When he proposed to her, she accepted, but on condition that he change his name. So Gusti Kohn became Gusti Kastner and Rosl Karolyi became Frau Rosl Kastner. Rosl was attractive, charming and liked fashionable places. Here you see her on an Italian beach in the early 1920s.. Unusually for the time, Rosl also worked at a bank in Vienna and earned a good living.

Gusti was quite adventurous in his business dealings. In the uncertain times that followed WW1, he made highly speculative investments, which went massively sour in the early 1920s, after the Austrian economy entered a financial crisis, followed by hyperinflation. To avoid bankruptcy (or perhaps to escape creditors), Gusti promptly left for Argentina, a place where, he had heard, good money could be made quickly. It wasn’t clear to him whether the South American adventure would prove fruitful, or when he would return to Vienna, so he and Rosl agreed that she would stay behind. Gusti did settle successfully in Buenos Aires and invited Rosl to follow him to South America a few years later.

In Argentina, Gusti and Rosl were reasonably well off, but Rosl felt that more could be done to improve their income. She decided to open a small hotel, focusing on the many Europeans arriving in Buenos Aires. Initially, she just rented rooms to the newly arrived, but after a while, noticing that most of them were men, she started to provide typical Viennese meals. This was soon after followed by ‘entertainment’. The family has never been clear about what Rosl’s hotel’s ‘entertainment’ was all about, so I leave it to your imagination what this might have been. In any event, it was a very successful establishment, which made Rosl quite rich.

Rosl’s ‘pension’ also provided her a very welcome social environment, where she often met attractive men who spoke German. Two of them would play a central role in her life: Paul Wachsmann, who became her second husband around 1945 and Otto Bornstein, who, not being able to conquer Rosl, settled for Ilse, Rosl’s daughter, whom he married in the late 1940s. Two children would be born from Ilse and Otto’s marriage (Suzy and Miguel Bornstein).

Rosl was good in business, but terrible with languages. She lived almost 70 years in Argentina, but was never able to properly articulate sentences in Spanish. Some of her gaffes became legendary. In the 1930s, the most stylish shop in Buenos Aires was Harrod’s. It was fashionable at the time for women to wear long-sleeved gloves, often reaching to the elbow (‘codo’ in Spanish). Rosl, who not only liked to go to Harrod’s, but wished to make sure that everyone realised she was there, upon arrival once said in her loudest voice: ‘Señorita, tiene Ud. guantes hasta el culo?’(‘Do you have gloves till the ass?’). On another occasion, Rosl asked two startled painters, who she had ordered to her home to paint the ceiling (‘techo’ in Spanish): ‘Puede Ud. pintar mi pecho?’ (‘Can you paint my breasts?’).

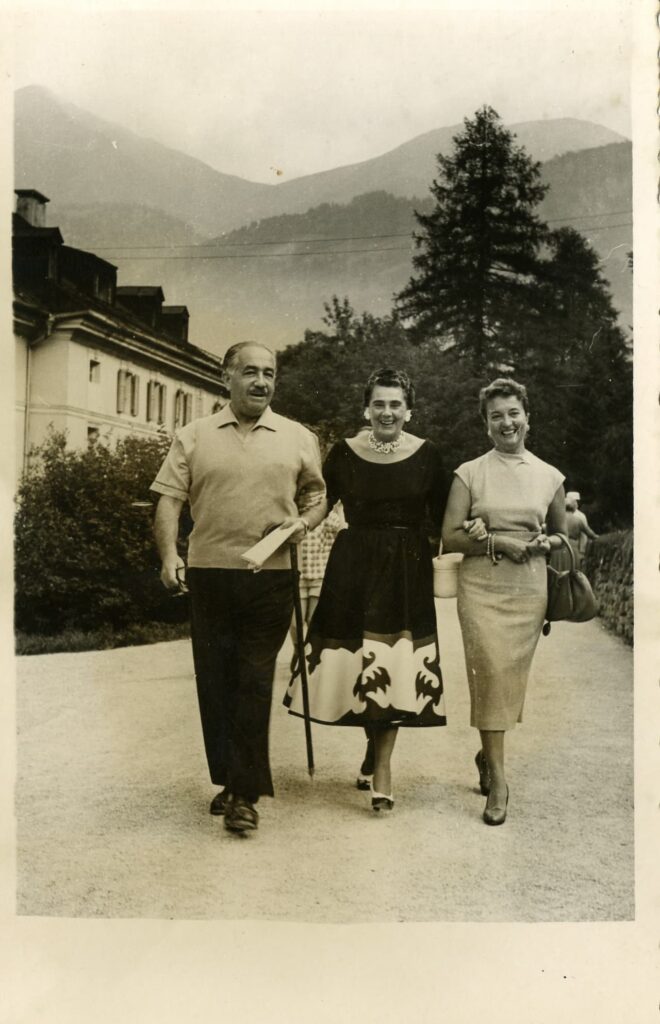

Rosl and Paul Wachsmann led a very comfortable life. Around 1941, on Rosl’s prodding (they were not married at the time), Wachsmann had set up his own business in grain exports. At a time when the world was at war (but Argentina was not), it was an excellent business to be in and the enterprise was very successful. The Wachsmann’s became rich and they liked to show it (especially Rosl). Starting in the late 1940s, at least twice a year, they would travel in great pomp to Europe, Rosl accompanied by at least 10 suitcases. They stayed in Bad Gastein, where Rosl liked to parade in the latest fashion. Their return to Buenos Aires was always a cause for celebration, with the whole family coming to receive them at the airport.

Upon their arrival in Buenos Aires in 1946, Szigo, Lilly and Paul were immediately taken care of by Rosl, who arranged for them a very nice apartment in the Calle Juramento in Belgrano (not far from the centre of Buenos Aires). Here Paul, at the age of 19, for the first time had his own room. Both Paul and Szigo were given jobs at Paul Wachsmann‘s flourishing business. Lilly received from her sister what was most important to her: several fashionable hats and, I imagine, a few white gloves “hasta el culo”.

Paul stayed at Wachsmann’s for five or six years, but became increasingly unhappy there. The business was flourishing, but Paul Wachsmann ran his enterprise in a very old-fashioned way, giving stern and unappealable orders, and acting like a dictator. My father had to start ‘from the very bottom’, carrying the mail and performing other administrative, and mostly mindless tasks, even though Paul Wachsmann knew that his nephew had had much more responsibility in his last jobs in La Paz.

In 1951, Paul Wachsmann asked (no, ordered) my father to move to Montevideo, Uruguay, to take care of the grain trading’s small subsidiary there. Initially, my father was thrilled to be away from the suffocating presence of his uncle, but after a short while he realised that distance changed nothing, and that Paul Wachsmann was just as dictatorial on the phone as he had been in the office. The job in Montevideo left my father enough free time, so he tried to develop additional business for the company, only to be told that this was none of his business.

After a year or so, longing to be with Lisl, who at this time he was already engaged to, Paul returned to Buenos Aires and told his uncle that he was bored and wanted a more entrepreneurial occupation within the company. The response was: ‘It’s me, not you, who will decide what you do and when’. When Paul heard this, he decided to resign on the spot.

This created shockwaves in the family. Over a hastily arranged lunch, Rosl confided in my father that her husband Paul (who she admitted could behave in an ‘old-fashioned’ way), much admired my father and saw him as his successor. Paul, however, was unmoved, and said to Rosl that ‘enough is enough’ and confirmed that he was leaving.

My father, now aged 24, repeated what he had done at Leon Weil, when he was 15: when he thought an environment was not right for him, and/or he felt that he had been treated unjustly, he had the confidence in himself to just leave. I would do exactly the same thing during my business career. Whenever I felt that my path was blocked or that I was not treated fairly, I left—without a thought for the short-term consequences. This, and so much more, I owe to the example of my father.

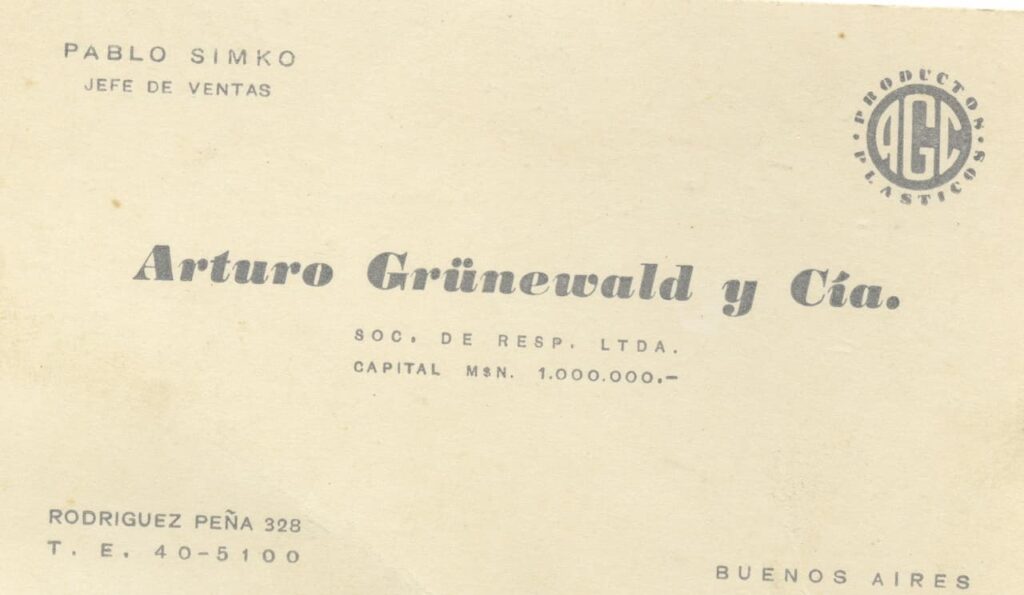

Paul placed an ad in the German newspaper: ‘Expert in import/export, speaking perfect Spanish, German and English, is looking for a challenging position.’ He received four proposals for interviews: with the renowned, large firms Swift, East Asiatic Co and Alpargatas, and with a small local company called Grünewald. Paul chose Grünewald because the conditions were exactly the opposite of those at Wachsmann: the owner did not want to work much, he was in fact looking for someone to take the initiative and run the business, while he could relax. Herr Grünewald enjoyed spending three months a year in Europe, three in the US, three in Punta del Este, Uruguay and three (and only if necessary) in Buenos Aires.

For both him and my father, it was a perfect solution, and Paul signalled that he was eager to take the job. However, a last hurdle had to be taken care of before Paul could be hired: Herr Grünewald was good friends with Paul Wachsmann. He insisted on seeing his friend and asking for his permission to hire my father. Paul Wachsmann bit his lip, but did not object to Grünewald hiring his nephew. And so, Paul started in a novel and very exciting environment, one that would later offer him the tools to start his own business.

Szigo was also unhappy in his job at Wachsmann’s, where he was given administrative duties at the port. However, he was less enterprising, severely limited in his language skills (he spoke mediocre Spanish and no English), and not particularly efficient in what he did. He nevertheless left the family business at about the same time as my father and started work as a salesman for a manufacturer of handbags. He was not good with numbers, rarely wrote down details of his transactions and relied on his memory to do business. At some point, the company owners accused him of having kept some of the money he had received from his customers (something that was apparently not true). My father had to intervene and solve the problem by repaying the owners out of his own pocket over a period of several months. From then on, Szigo held small jobs, often felt depressed and only flourished again when my father, in the early 1960s, hired him to help out in Simko SA.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko