Throughout their lives, Paul treated his parents with unconditional love and immense tact. He solved his father’s on-the-job problems and discreetly paid his debts, without ever making Szigo feel bad about it. While often making fun of his mother to the rest of the family, Paul always catered with the greatest attention to her whims. Her pedantic ways may have frustrated him, but he saw it as his duty to take care of her wishes with the greatest devotion. Paul’s example greatly impressed us children and it was his conduct that inspired us to do likewise when Lisl would fall ill in her later years.

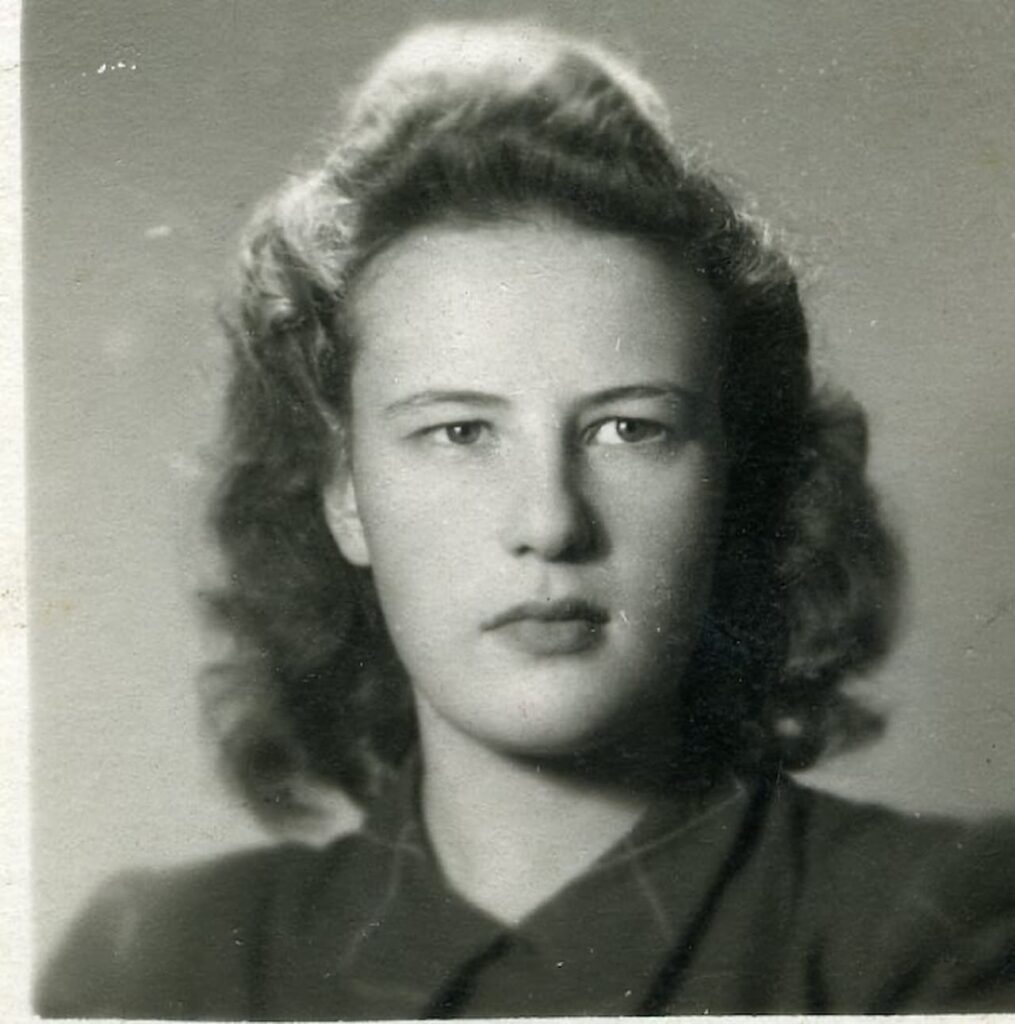

My parents met in 1947 at the Österreichische Jugendgruppe in Buenos Aires, the exiled Austrians’ association. My father was rapidly attracted to my mother’s fragile and angelical look. But what really made my mother irresistible were the Ellmanns. My father found in them, especially in Fritz, an inspirational guide and teacher who would help him acquire some of the culture his lack of formal education had prevented him from obtaining. In Heinz, Lisl’s younger brother, he found the sibling he had never had. And Mimi, with her warm character, her musical talent and her great cooking, created a family environment that my father just loved. The Ellmanns liked my father too—he was earnest, hard-working, always good-humoured and extremely enthusiastic. Lisl, who initially hesitated, was rapidly seduced by father’s charming nature, self-assurance and constant optimism, which she instinctively felt would be a good antidote to her melancholic and self-doubting nature.

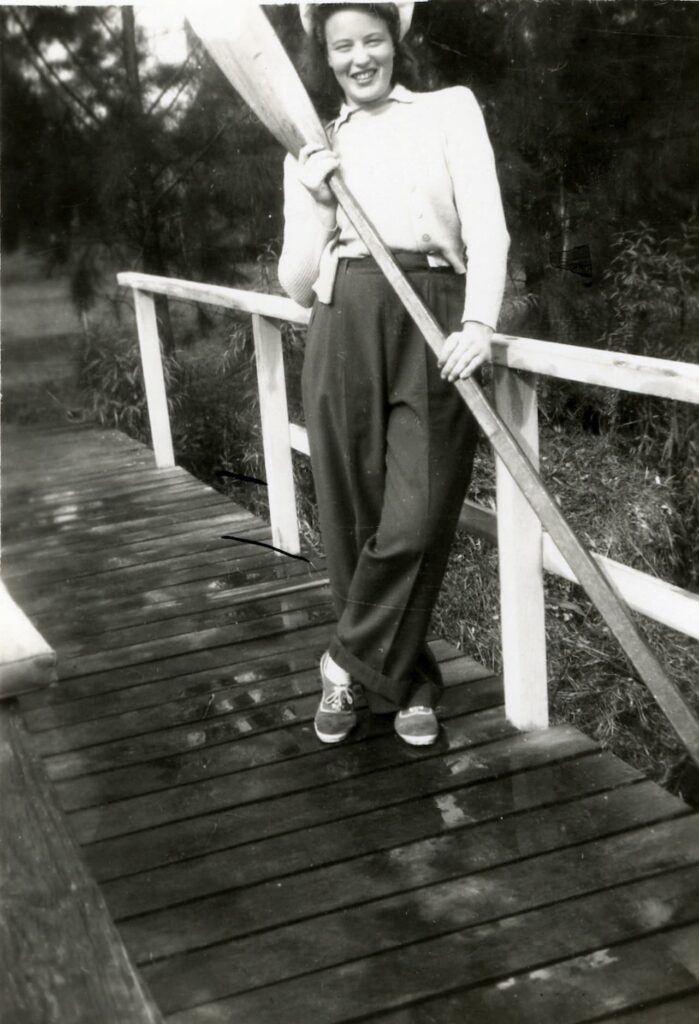

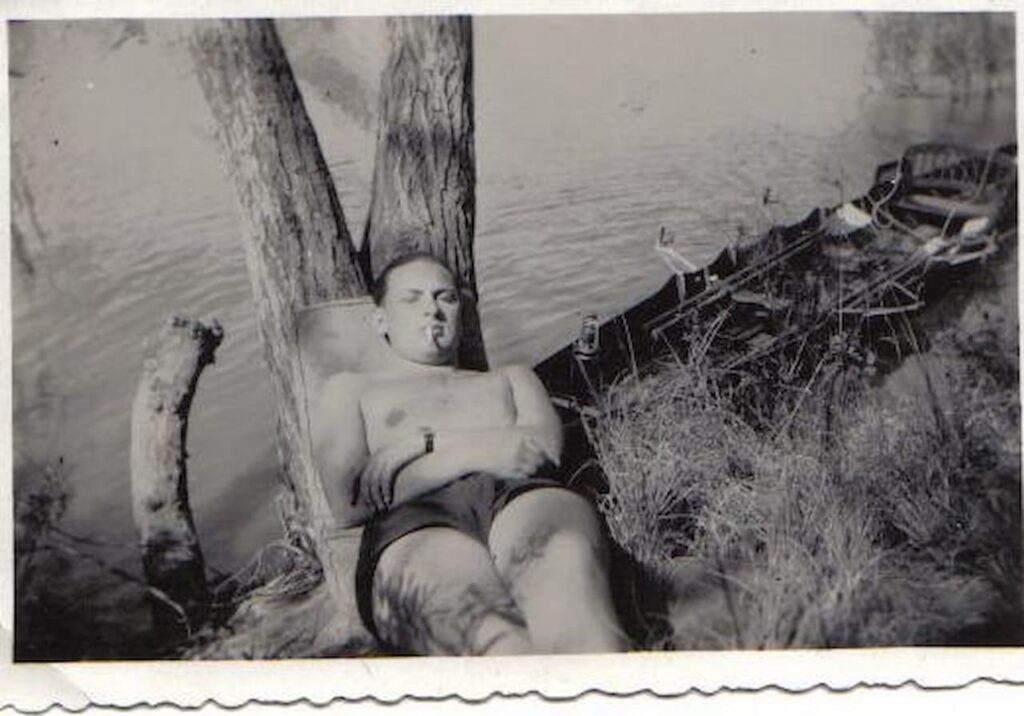

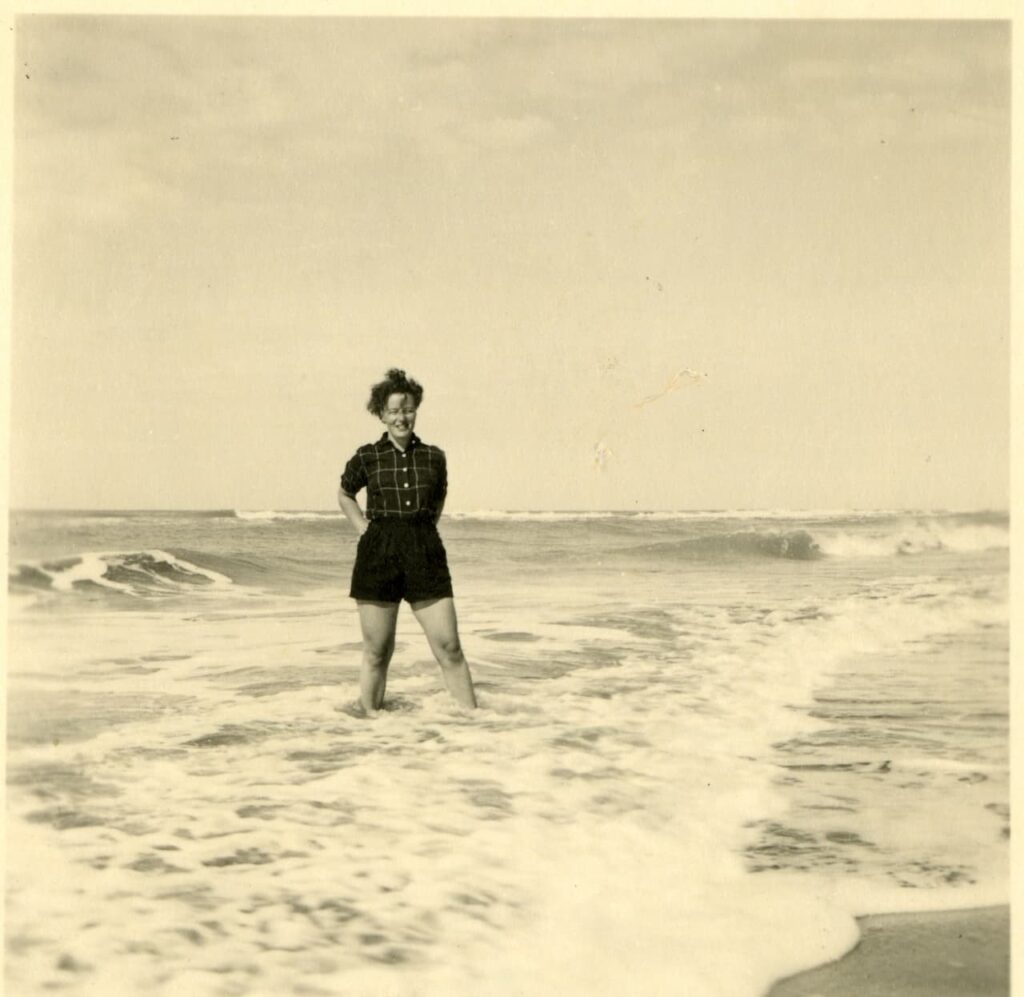

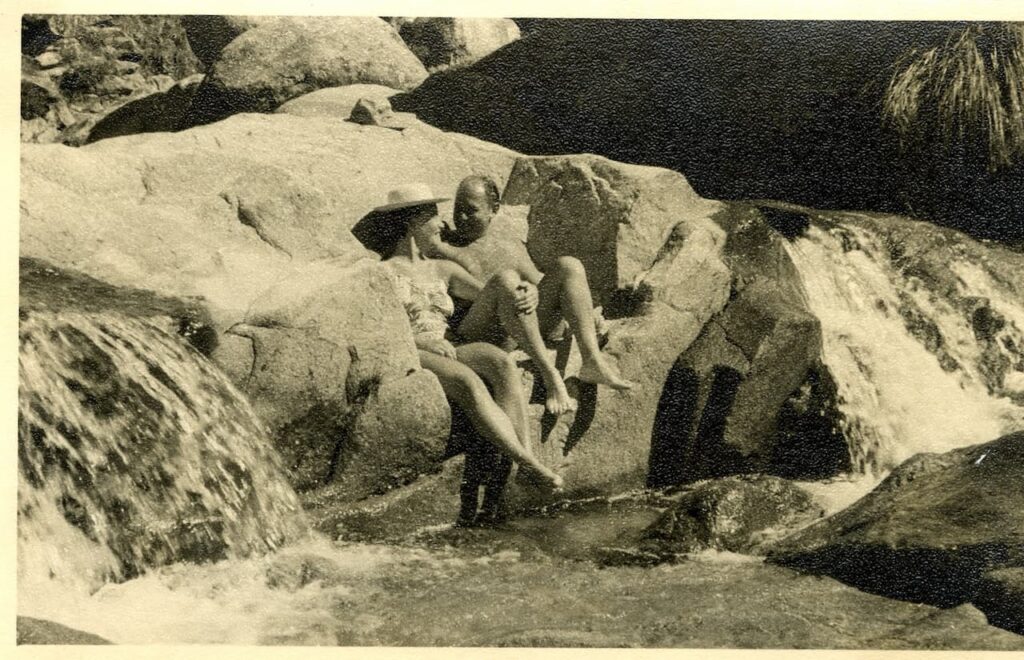

My parents would get married only in 1952, but from 1947 onwards they spent most of their time together. Their friends all came from the Austrian community and they had an active social life, which included ballroom dancing, enacting plays, excursion to the Tigre (the Rio de la Plata’s delta) and many other areas of Argentina. Most of the members of the Österreichische Jugendgruppe were politically left-leaning, including a few communists. This did influence my mother, who remained politically to the left for the rest of her life, but not my father, who always despised socialism and communism.

In the initial three or four years following their marriage, Lisl and Paul lived at the Ellmann’s, where Fritz re-arranged for them the first floor at the Calle Pareja, and included a small kitchen.

Lisl, Heinz, Paul and especially Fritz’s existence was considerably shaken around 1953 by the arrival on the scene of Annie Pollack, who would in many ways influence, if not transform, the life of all of them, and that of the next generation.

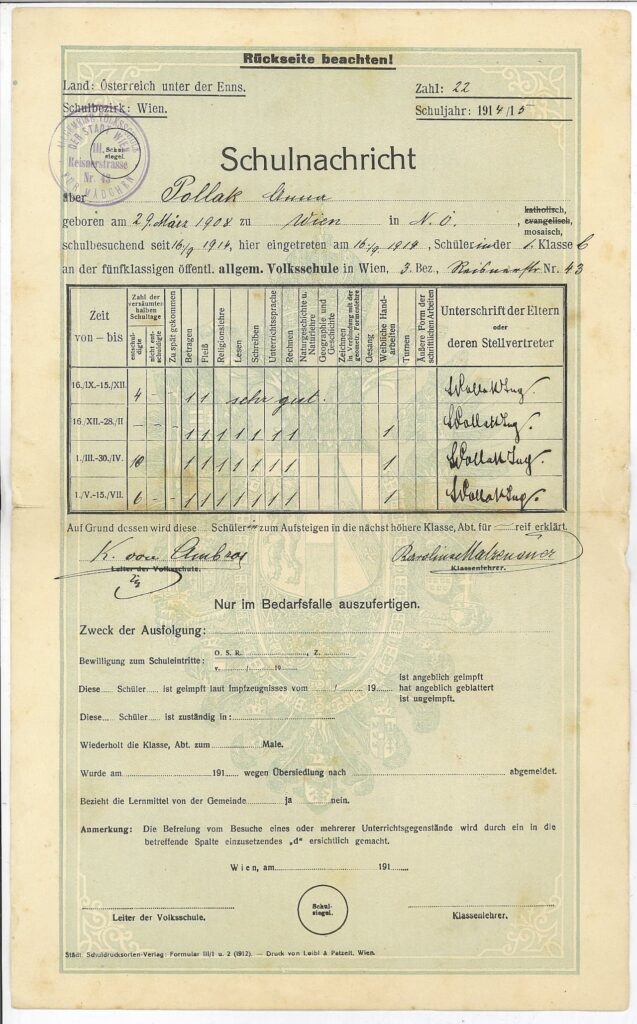

Annie was born in Vienna in 1908 into a Jewish family, which was originally from Prague. The Pollacks were wealthy and Annie grew up in a cultivated environment that shielded her from any material needs. Her school certificates show that she was an outstanding student. She was not the world’s most attractive, but she was not ugly either. She married a Mr. Bär in Vienna in the late 1920s and they moved to Buenos Aires almost immediately thereafter. She had a sister, who emigrated to the US in the 1940s and who would die quite young, in the early 1960s.

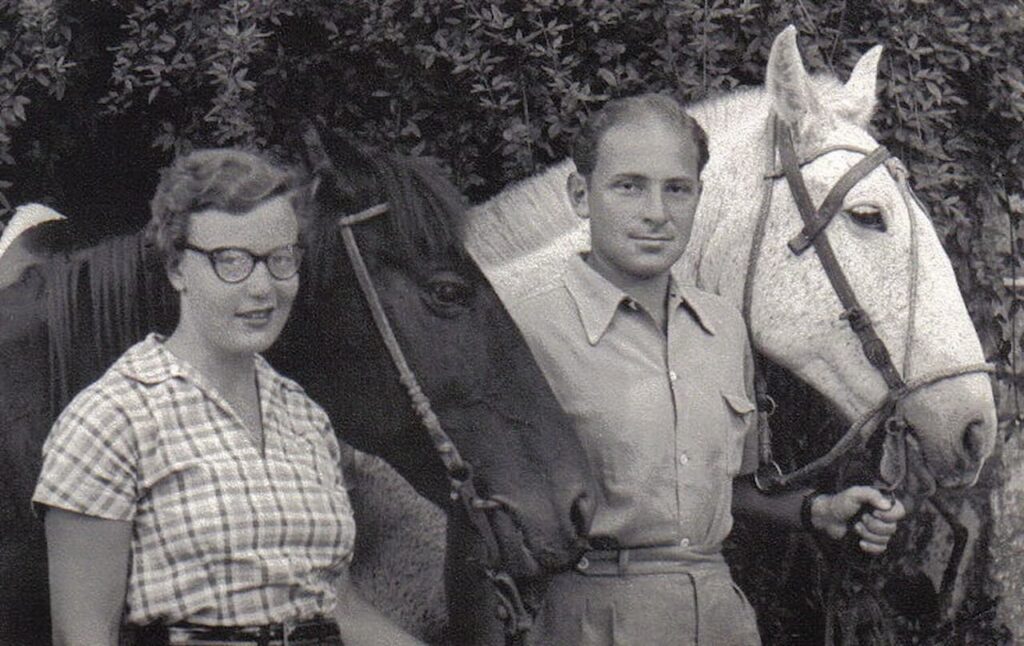

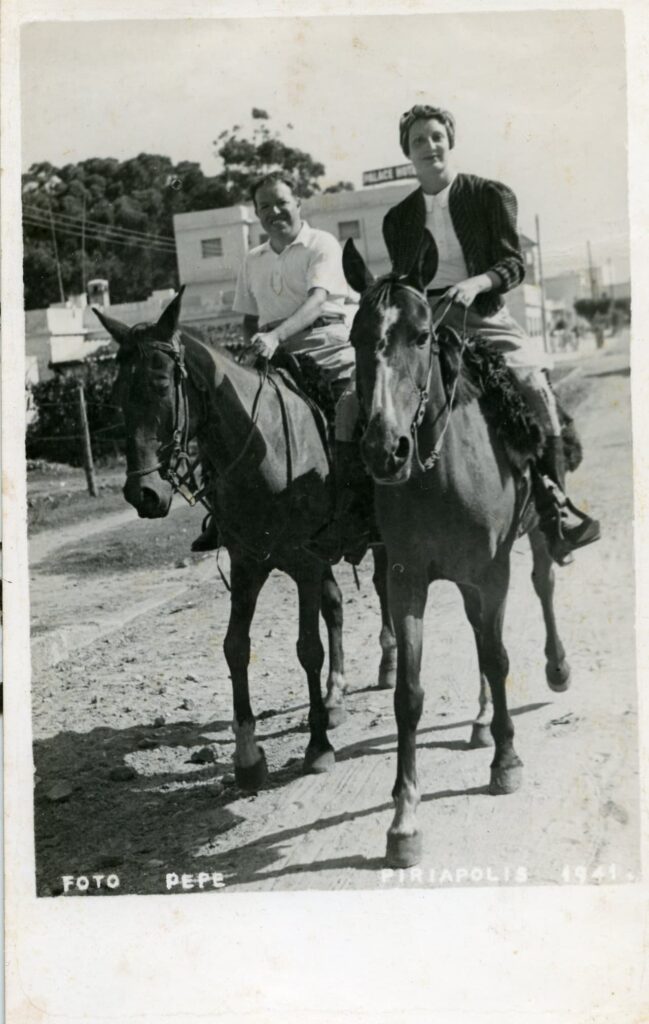

It’s not known what Herr Bär did for work in Buenos Aires, but according to all accounts he and Annie led a materially comfortable life and their marriage was a happy one. They travelled extensively through Argentina and Uruguay. Both had a passion for horseback riding. She learned Spanish well, certainly a lot better than Szigo, Lilly, and of course Rosl. Despite a strong German accent, she expressed herself very well in Spanish and could read and write flawlessly.

Literature attracted Annie from an early age and she read abundantly in German, English and Spanish. Her circle of friends was mainly composed of immigrants from Austria or Germany, but she was better integrated than most Europeans, and over time developed close friendships with native Argentinians, including a long and fruitful one with the famed Argentinian writer, Jorge Luis Borges.

Fritz had been good friends with Herr Bär for many years, until the latter died in the late 1940s. After Mimi’s death in 1951, Fritz and Annie got closer, began to see each other regularly and finally married in the mid-1950s.

The arrival of Annie into the family initially created shockwaves for Lisl, who saw in her a competitor to her beloved mother, whose death she never really overcame. But over time, Annie won over the heart of my mother and they became inseparable until Annie’s death in 1988.

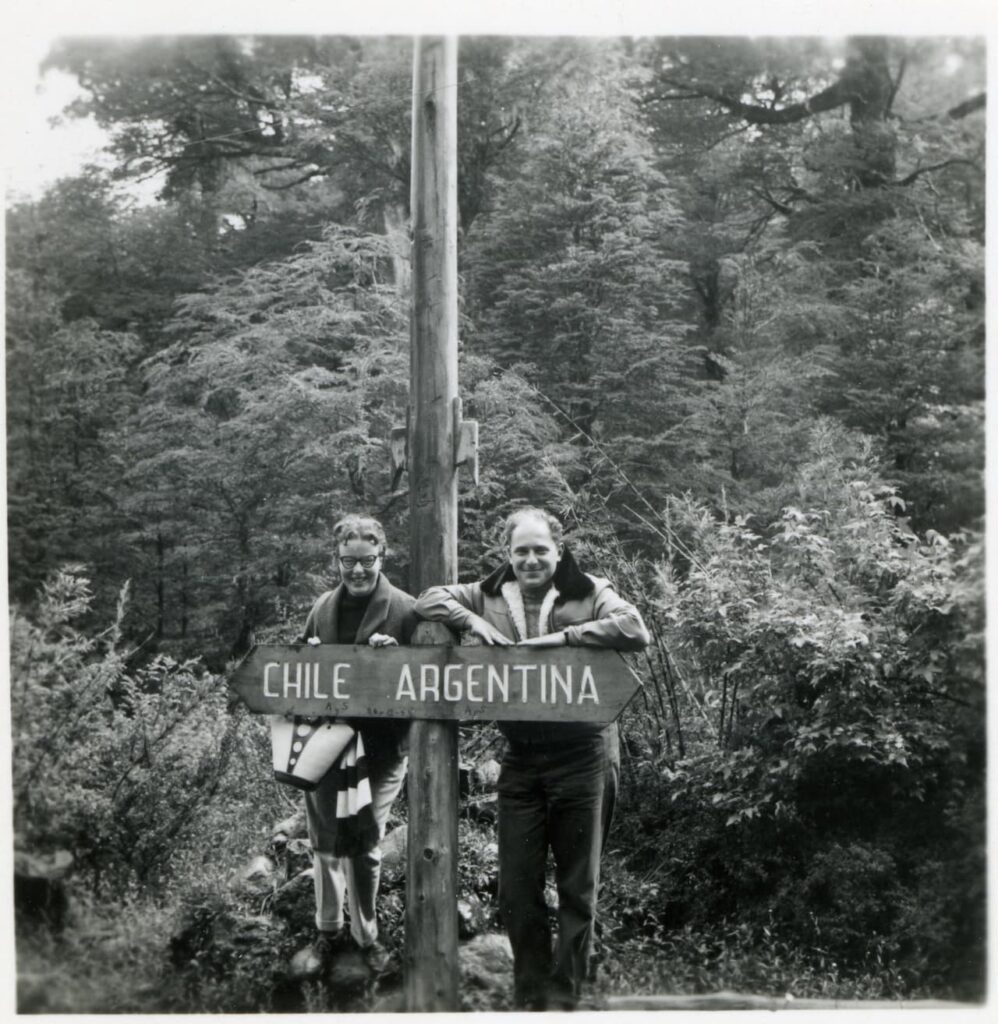

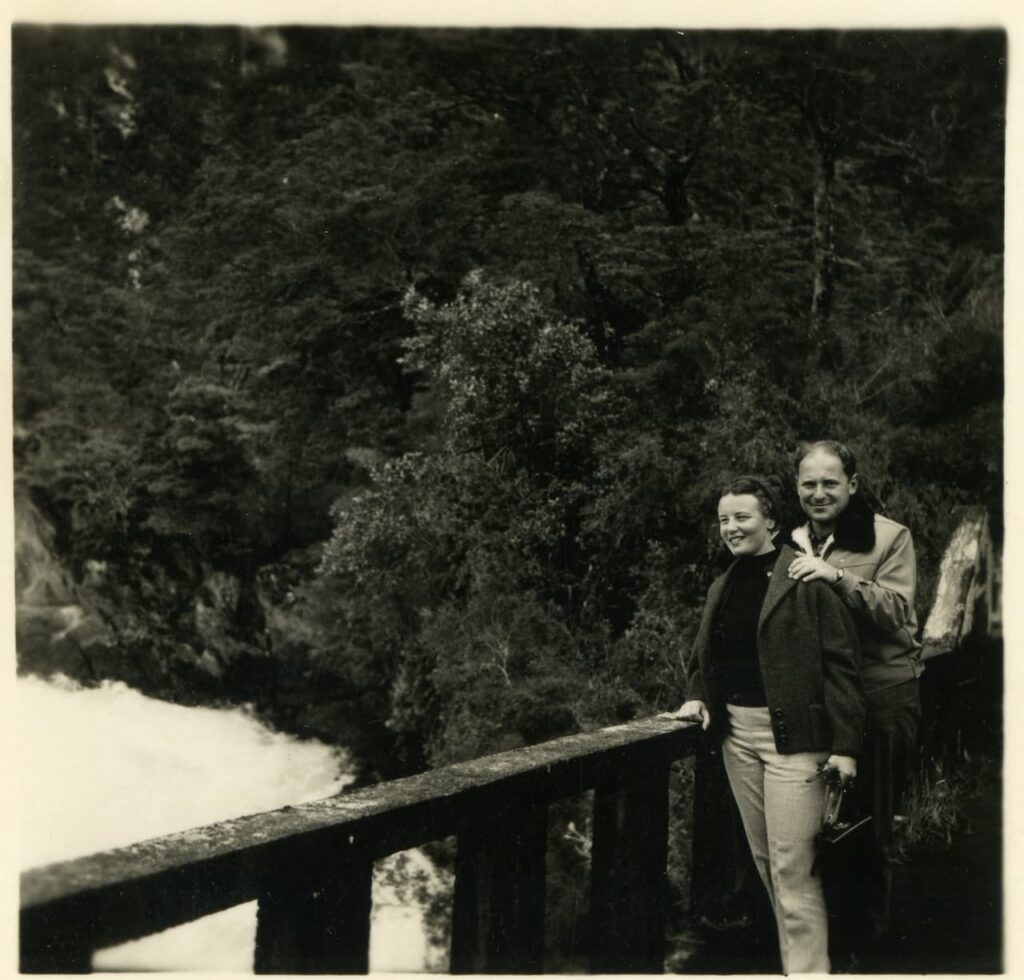

Annie gave a second life to Fritz, allowing him to forget the early death of Mimi. By all accounts, they had a very happy marriage. They both loved literature, the arts and the outdoors. Like Fritz, Annie was an assimilated Jew. She never attended religious services and celebrated Christmas not in any religious way, but as a great family get-together.

After their marriage, Fritz moved into Annie’s home in Calle Washington 478 in Beccar, in the outskirts of Buenos Aires. Paul and Lisl moved to an apartment of their own in the Calle Quintana 2430 in Olivos, not far from the centre of Buenos Aires. This is the place where I would be born. Heinz, now in his early 20s, also moved out, so the house in Calle Pareja in Villa Devoto (which was rented) was let go.

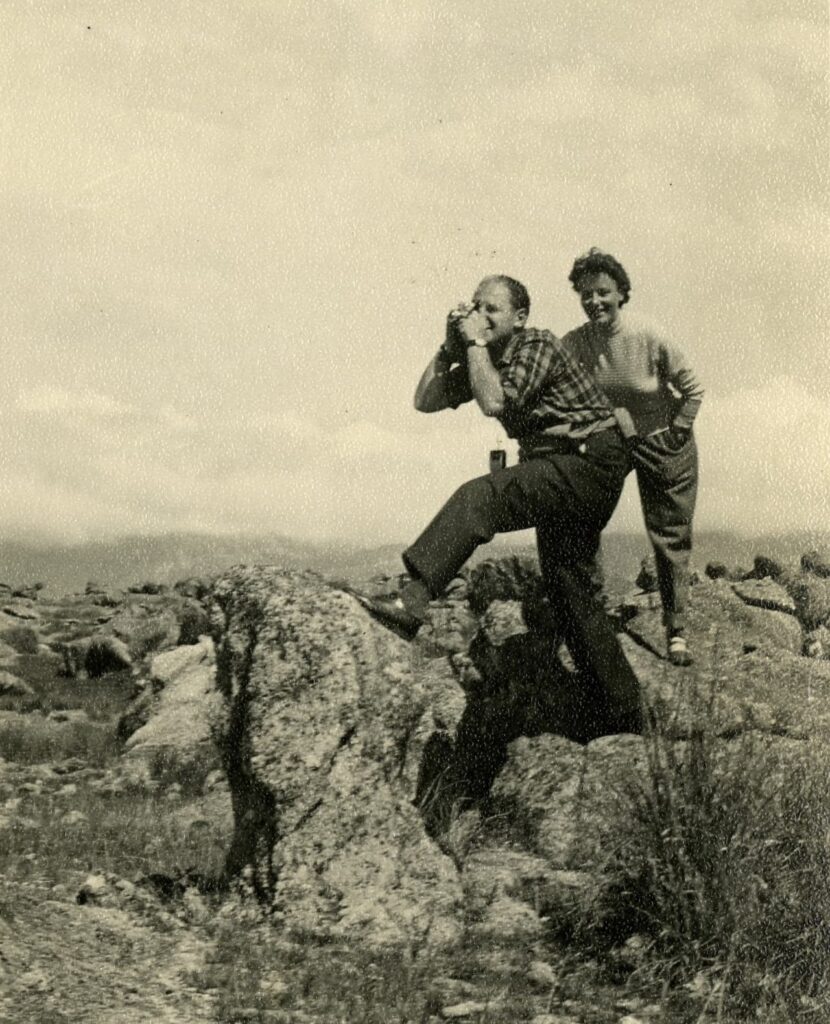

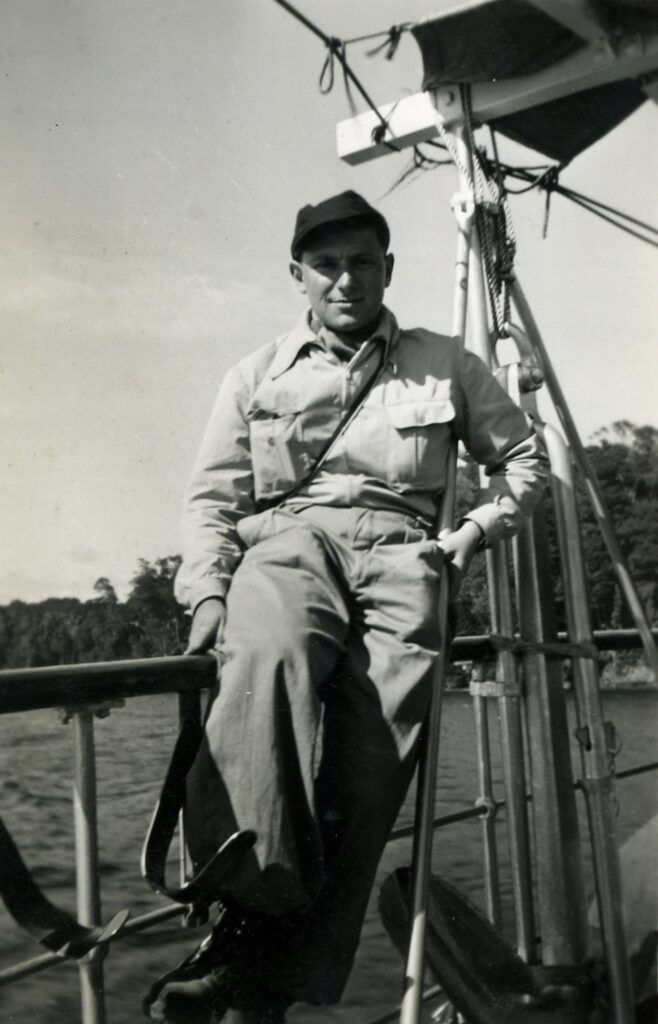

One of the great attractions of having joined Grünewald in 1954, was that from the start Paul had access to a car, which he was allowed to use on weekends too. He was incredibly proud of his rastrojero, a small utility car with which he could transport not only materials, but also groups of people. It was in this pickup truck that an elated Paul picked up a large crowd along the streets of Buenos Aires and took them to the Plaza de Mayo in 1955 to celebrate the fall of Perón. During these early years of their marriage, my parents travelled extensively through Argentina, with a special predilection for Bariloche, where many years later my brother Eduardo would buy a wonderful house. When not on their own, they travelled with friends, often with Fritz Hacker, who conveniently owned a wartime jeep, perfect for the discovery of Argentina’s numerous beaches.

The mid-1950s were a happy time for my parents. Materially they had enough to lead a simple, but fulfilled life, their relationship was good and, especially my father (who already at the time was very influenced by political events), saw a bright future in Argentina, following the exile of Perón. It was at this time that Paul and Lisl decided to become Argentinian citizens, a decision that was strongly motivated by devotion and patriotism towards a country which had offered them asylum, had allowed them to meet, and in which they were now ready to build a family.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko