By the time I was born in 1957, Paul had left Grünewald and had started his own business. Around 1955, his astute smell for opportunities had indicated to him that importing rubber and materials for the rubber industry offered a better opportunity than shipping to Argentina finished goods, such as tyres, as Grünewald had been doing. Argentina was beginning to industrialise and the government was increasingly protecting the local industry. Paul suggested to Grünewald to focus on raw materials, but the owner resisted. So, Paul set up his own business, initially in the offices of Grünewald, subsequently in spare offices that Paul Wachsmann put at his disposal (despite Paul’s departure, the two Pauls had kept a very cordial relationship).

Initially Paul worked on his own, but Lisl helped him. She had acquired secretarial skills, spoke perfect English, German and Spanish and had worked as an executive secretary before my parents were married. It was a short-term solution, and as soon as my father had sufficient resources, my mother was no longer involved in the business. Many years later, when the time came to set up my own business with Josée, my first wife, my father warned me: ‘It’s not a good idea to share your office with the same person you share your bed with’. I didn’t listen, with nefarious consequences.

With enthusiasm, great interpersonal skills, total dedication, excellent attention to detail, unfailing reliability and a strong gift for languages, Paul built up Simko SA into a very successful company, importing rubber and chemicals for the rubber industry to Argentina’s fledgling industry. He always invested in the latest communication technologies, no matter what the price (he had one of Argentina’s very first telexes installed in his office, which gave him a strong competitive advantage).

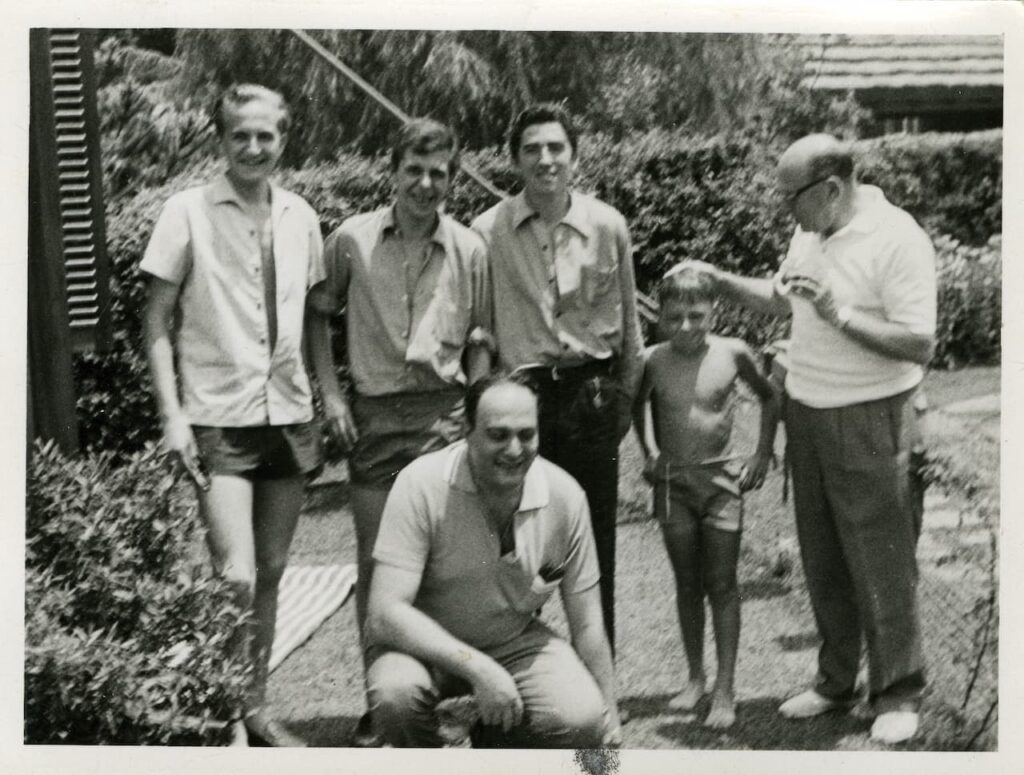

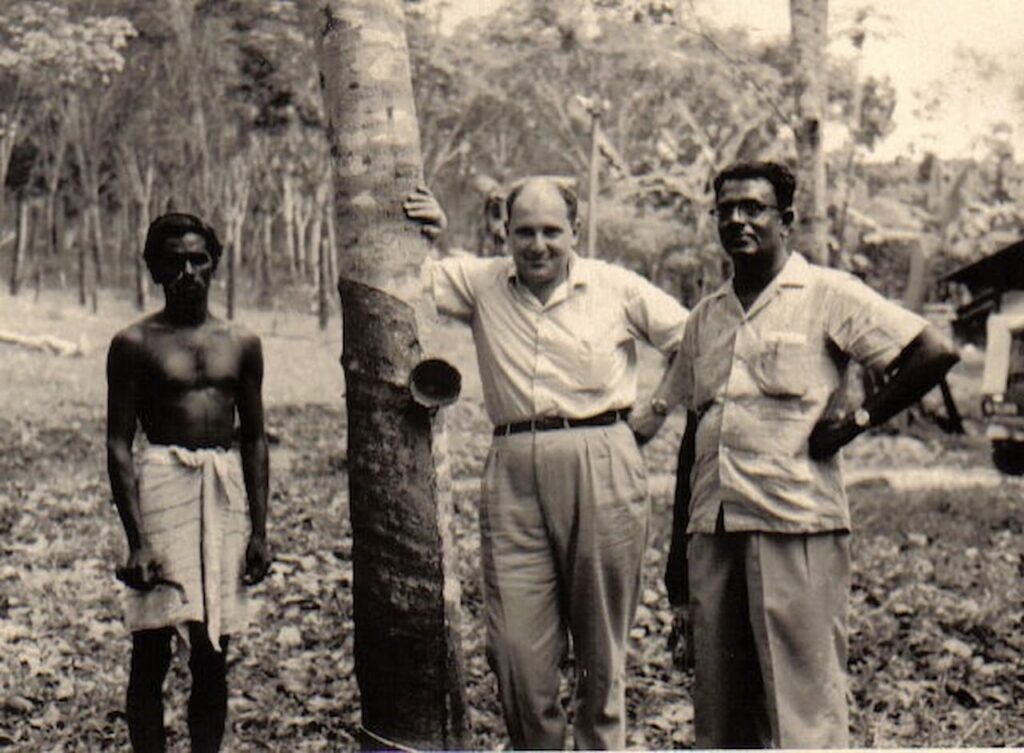

He thought long-term and was ready to take risks, if he thought it could help his business. In 1959, he did not hesitate to travel on short notice from Buenos Aires to Singapore, in order to solve a business problem that risked derailing his nascent relationship with Lee Rubber Co. At the time, the plane trip took about three full days and involved at least 10 stops, with frequent change of planes. The cost of travel was prohibitive, but Paul sensed it was worth it.

Upon arrival in Singapore, where no one had ever seen anyone from Argentina, two Chinese were waiting for him. Paul arrived on the flight he had indicated, but the Chinese duo, who were standing in the reception area, did not approach him. It was only after everyone had left that my father noticed the visibly anxious duo. He approached them and asked: ‘Are you waiting for Mr. Simko?’ ‘Yes’, they said. ‘I’m Mr. Simko,’ he said. ‘Oh,’ said the two Chinese, with surprised but very relieved looks, ‘most welcome to Singapore, Mr. Simko!’ It was only much later that my father understood what had happened, when the two Chinese confessed to him: ‘Two years ago, someone came to visit us from Brazil. He was very dark. So, we thought: more south, more dark!’

My father’s first trip to Singapore was a big success. He established what would become a lifetime relationship with K.C. Tan from Lee Rubber Co. It was a partnership founded on mutual trust and the greatest mutual admiration. My father would for many years have a competitive advantage in Argentina because his suppliers in Singapore (and elsewhere) would rely on his word and ship material without extensive paperwork. The same happened with his clients, who came to know him as 100% trustworthy. I grew up with my father saying: ‘What you say is the same as what you write; and what you promise, you must always deliver, no matter what the consequences’. This greatly impressed me and helped me, many years later, to build a successful business based on the same principles.

Paul had an innate sense for marketing. During his first trip to Singapore, he spent his evenings writing more than 200 personalised postcards showing exotic and beautiful images of Asia to clients and prospects in Argentina. This ensured that by the time he returned, everyone knew where he had been, which greatly improved the prestige of his (at the time still very small) business. When ships loaded with rubber arrived in the port of Buenos Aires, he would often use the occasion to invite clients on board and host a small celebratory dinner.

So, I was born into a small and happy family, where optimism reigned. While Argentina was clearly my family’s home, and my parents were very happy to live in Buenos Aires, they never forgot where they came from. The food, the manners, the culture and, especially, the language bore a constant reminder of Austria. When I was born, only German was spoken at my home, and at the age of three it was the only language I knew.

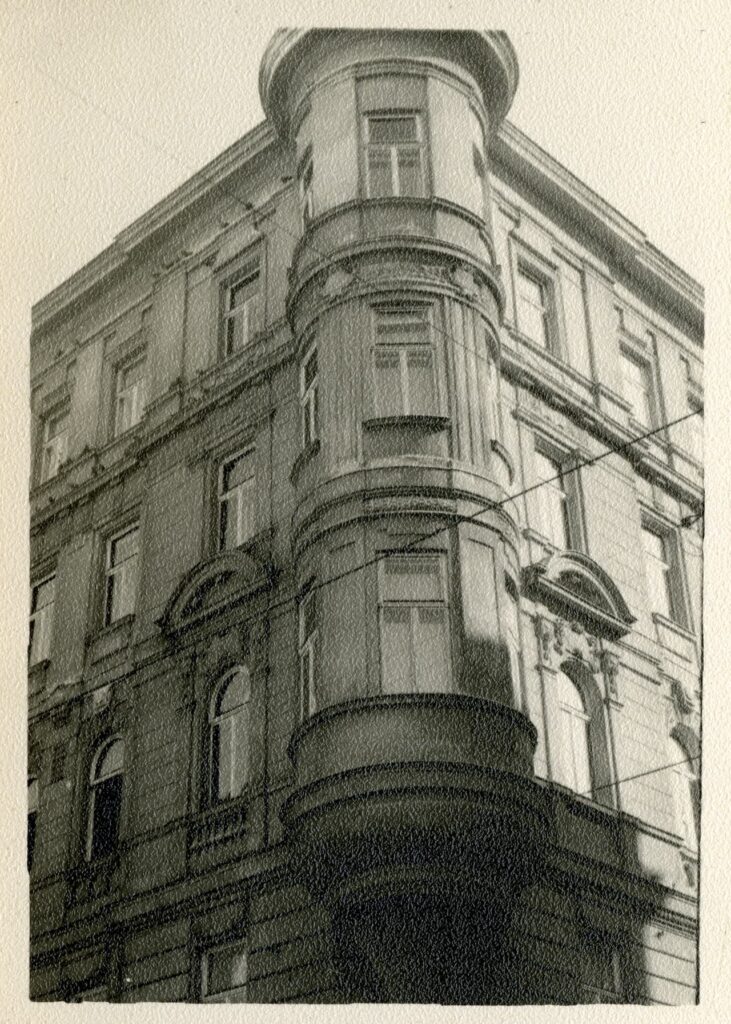

In 1959, Paul returned to Vienna, almost to the day 20 years after his departure. He had mixed feelings about going back to a city where he and his parents had been treated so badly. But in the end, curiosity overcame his initial misgivings.

Upon arrival, he refused to speak in German. Wherever he went, he presented his Argentinian passport, said that he was in Vienna on business and spoke only in English. After a few days, he took a taxi. The driver, about 18 years old, spoke only broken English, so my father had difficulty explaining to him where he wanted to go. Paul realised that this boy had nothing to do with the Nazis, that he had been born during the war and couldn’t have been an anti-Semite. So, he switched into German and proceeded to made peace with his hometown.

He returned to the apartment in the Grosse Stadtgutgasse where he had grown up, and the people living there were very kind and let him in. With nostalgia, he wandered the streets and realised how lucky he had been to escape. Vienna in 1959 had only recently been liberated from military occupation and presented a sad, downtrodden look.

While visiting the neighbourhood, Paul entered the Tabak around the corner from his former home, a place he had been to many times as a child. The attendant looked familiar, but quite aged. Paul asked her if she had worked in this shop for a long time. ‘Yes,’ she said, ‘I was here already before the war.’ ‘Do you remember a family called Simko?’ he asked her. ‘Yes,’ she said, ‘they lived very close. They had a lovely boy,’ she added. ‘That boy is me,’ said my father. The woman came from behind the counter and hugged him. Tears were in her eyes.

This event sealed Paul’s emotional return to Vienna. From then on, he would return enthusiastically dozens of times to Austria. He loved the food, the language and the culture, but kept a prudent distance from the Austrians themselves, especially those of the older generation, who he considered had behaved worse than the Nazis in the time between 1938 and 1945.

Eventually Paul would take every one of his grandchildren not only to Vienna, but to visit the apartment where he had grown up. Over the years, he developed very friendly relations with the successive people renting the apartment, who always allowed him to visit.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko