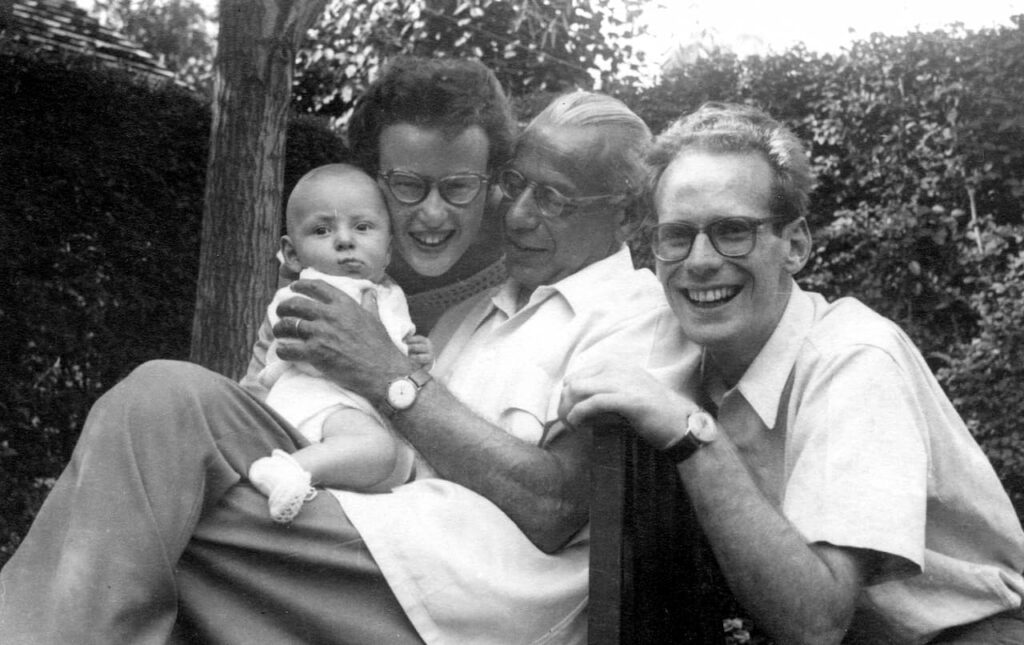

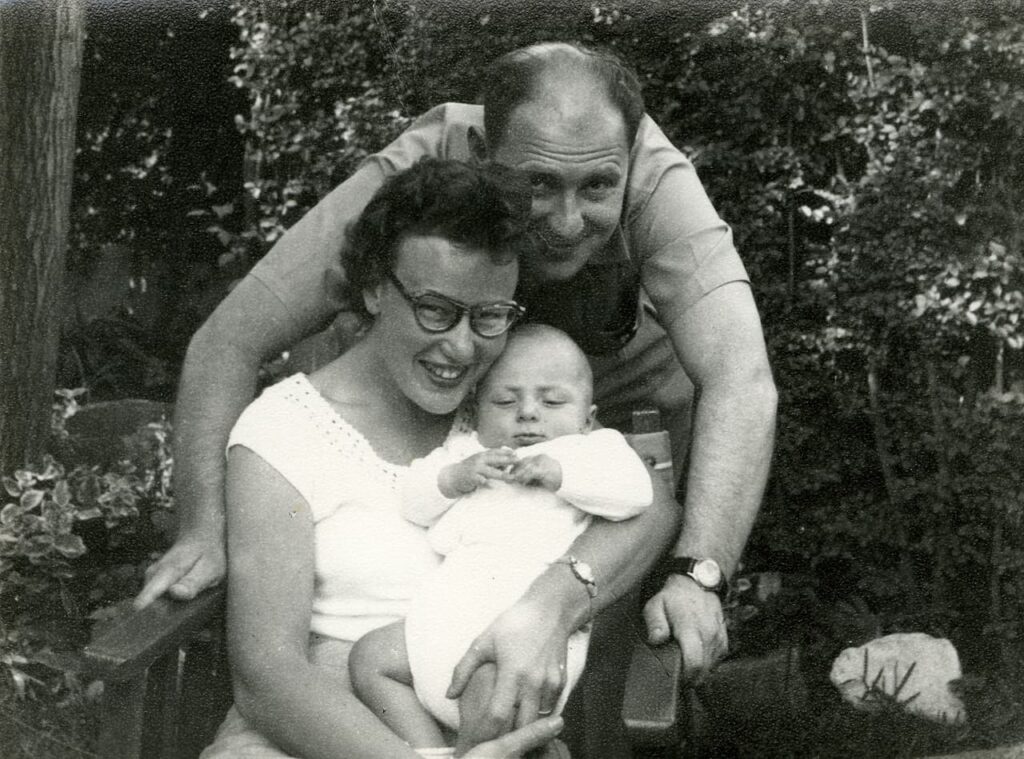

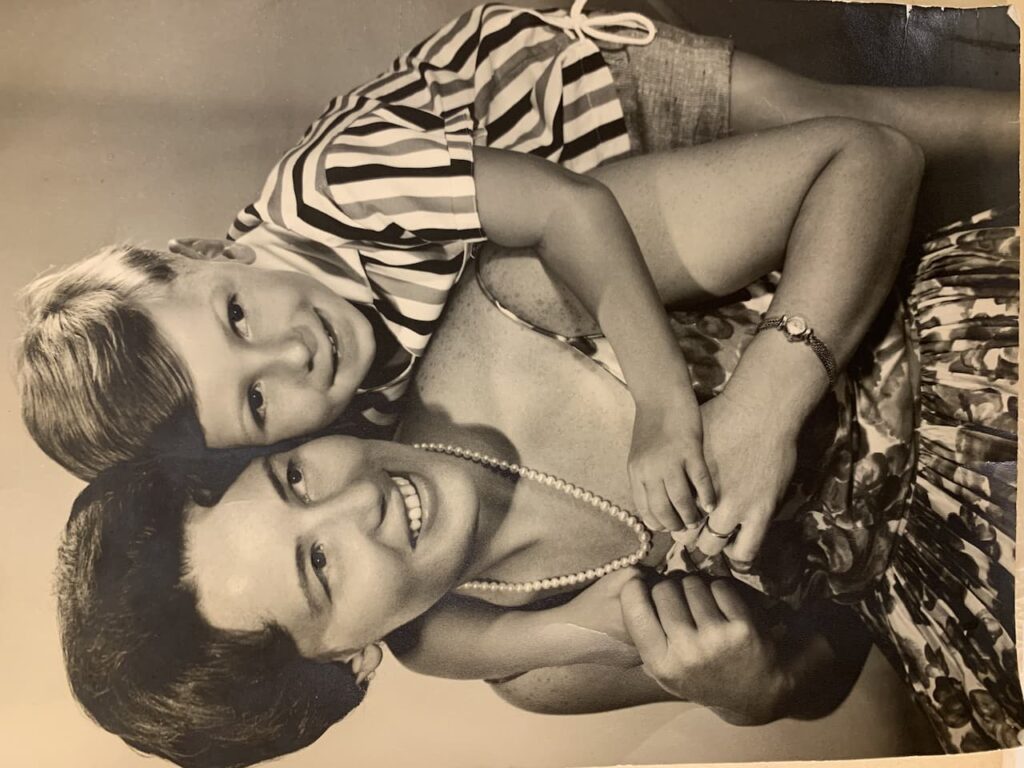

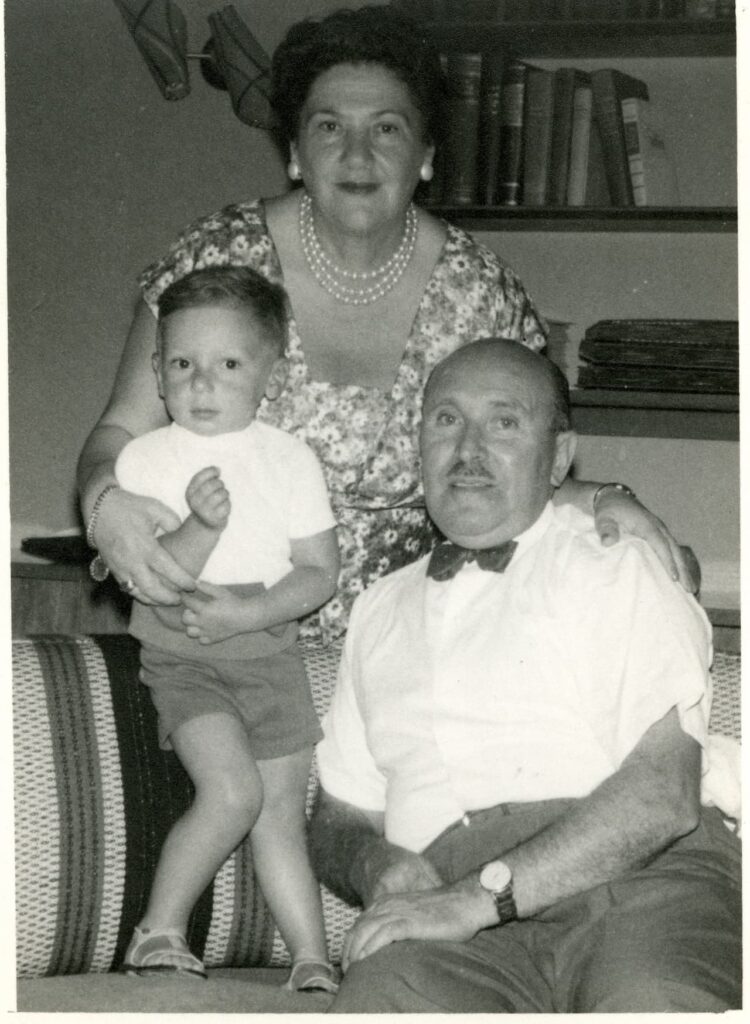

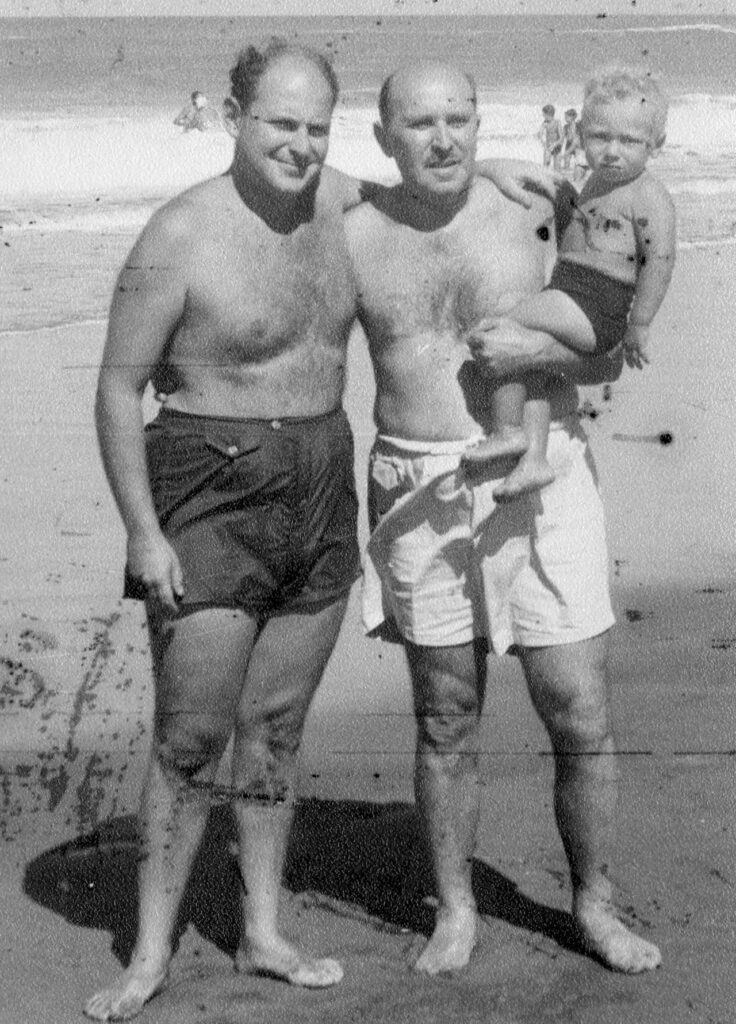

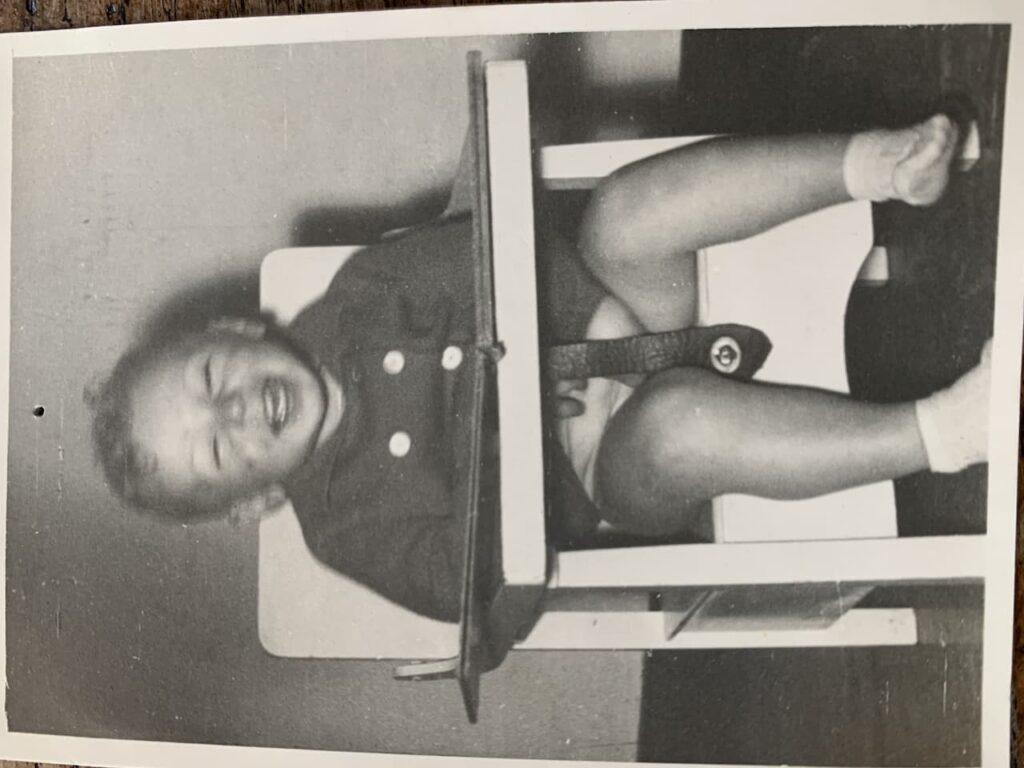

As the first of a new generation, I was welcomed with open arms and warmly taken care of by my parents, grandparents and all other members of our small, but tightly knit family.

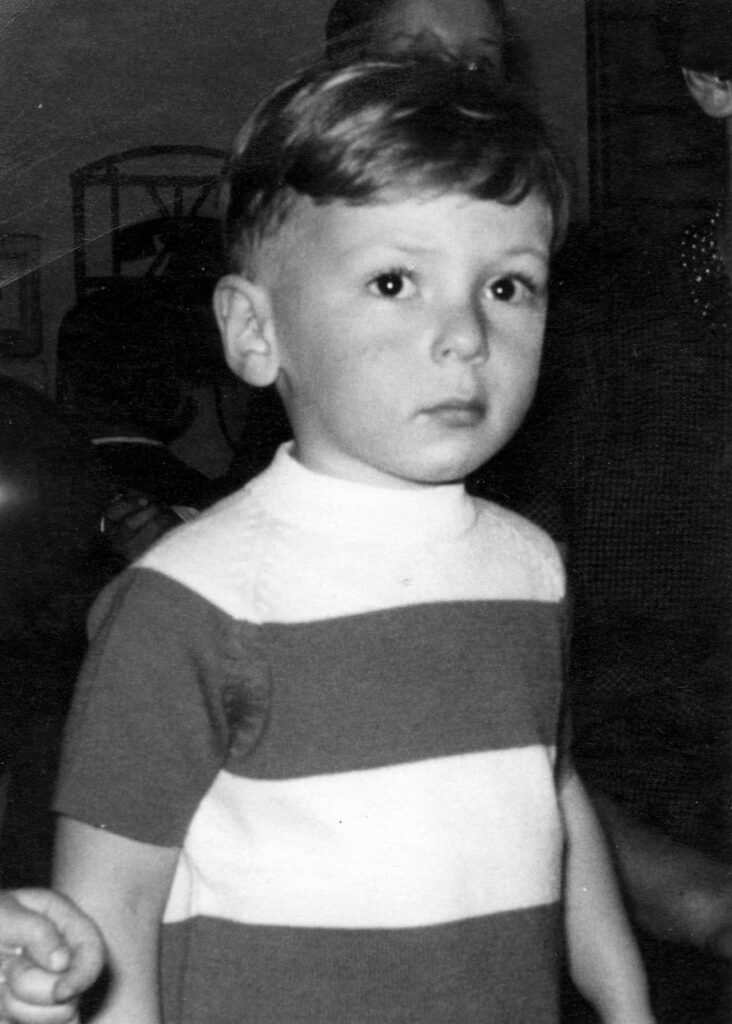

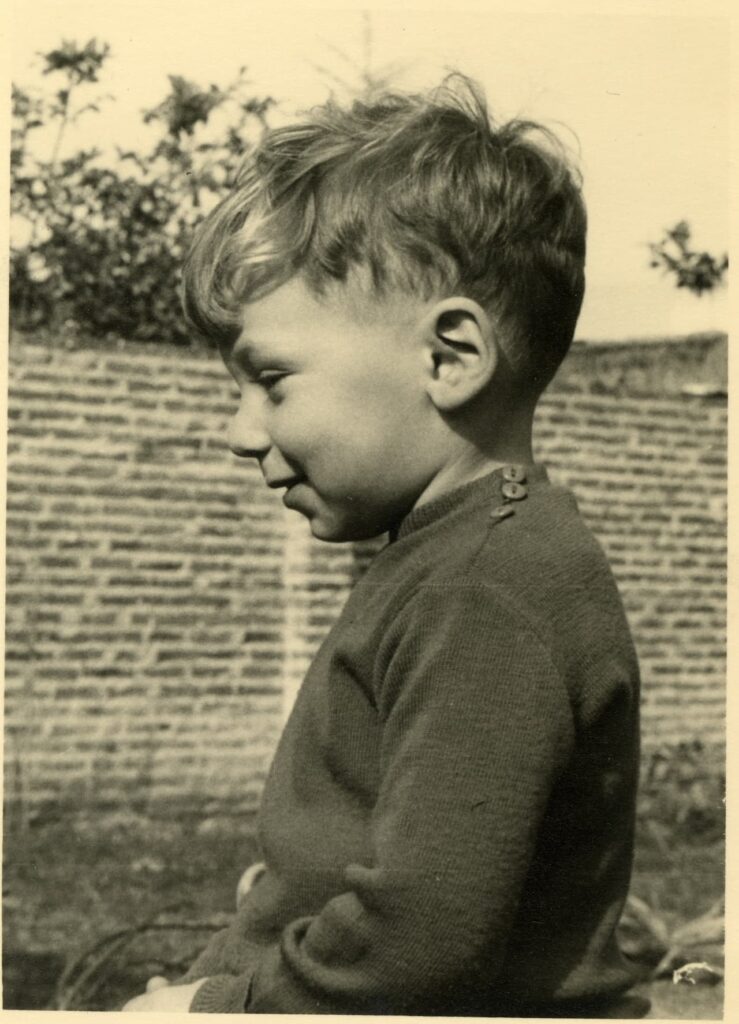

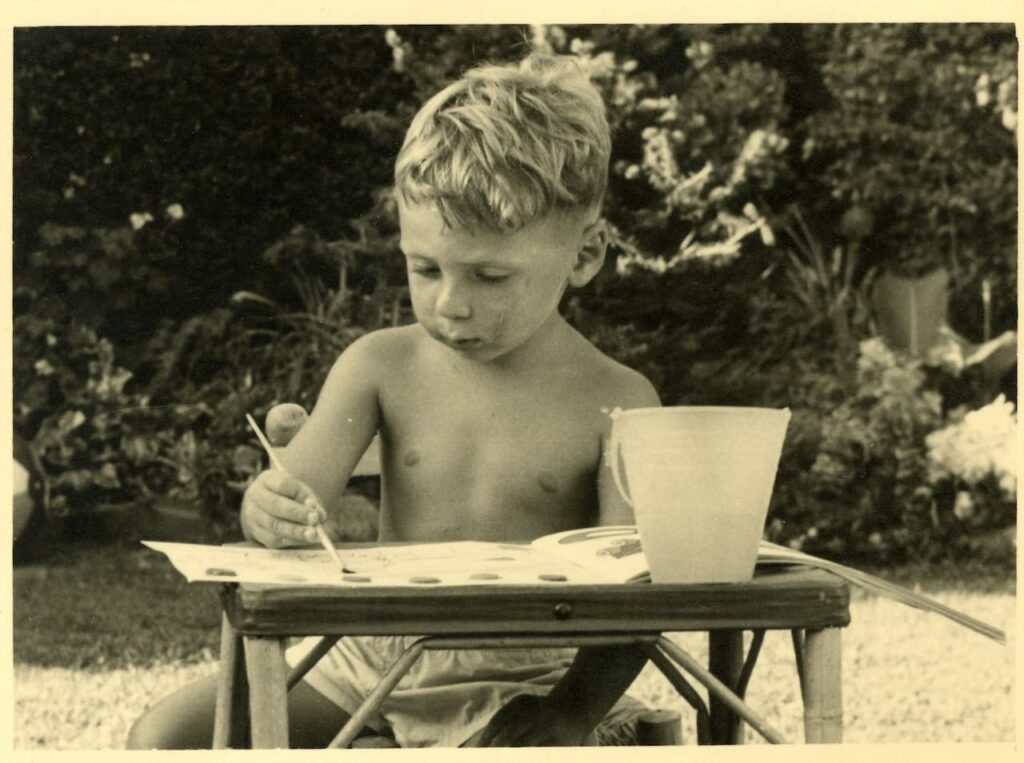

I was a sociable and extroverted child, with a strong sense of humour, and curious to understand the world around me. At age 4, I asked Lisl: ‘Mami, what is it like to think? I mean, what happens in the head when one thinks?’ Or: ‘Mami, why did God create thieves too?’ Or: ‘Mami, what are atom bombs and how do you build them?’

I had a firm point of view and was not shy to lay out my own interpretation of the world, as in this dialogue, when I was 4:

‘Mami, what happens when I die?’

‘You just fall asleep and don’t wake up again.’

‘That’s not true. I know from the books that you’ve read to me that people arrive awake in Heaven.’

Also, at age 4, during a walk with my father in the evening, under a very clear sky, with lots of stars visible:

‘Peter, aren’t these stars beautiful?’

‘What stars?’

‘Well, all those millions of stars we see up there – just raise your head.’

‘Those are not stars.’

‘What do you mean? What then are we seeing up there?’

‘What we see are holes in Heaven. Where God lives there is always sunshine!’

Also, to my father at about age 5:

‘You need to take care not to overload your brain too much. If you put too many thoughts into your mind, then they get thrown to the back of your head and you forget them. It’s only after two or three days of calm, that these thoughts come back to the front of the brain and you can then remember them.’

With my mother and Annie, after Lisl had related to us the story of a family of nine people, where the father lost his job and they had nothing left to eat, after a moment of reflection, I said: ‘Mami, can God not help? I mean, otherwise what is there for?’

To Annie, dressed as a doctor, wearing large glasses and white overalls, and after asking her to pull out her tongue: ‘The same as a cow, only a bit smaller.’ A comment to Annie, also at age 4: ‘A human being must always remain a human being, never a god. Can you imagine the confusion and mess if humans became gods?’ Also, to Annie: ‘I suspect that this is what happened.’ Annie: ‘Do you know what the word ‘suspect’ means?’ ‘Yes,’ I said, ‘”Suspect” is a little bit less than knowing.’

To my grandmother Lilly, after she complained to me that I behave so nicely towards her when it’s just the two of us, but as soon as other are present, I’m not nearly as kind: ‘But Omi, you should know that people behave differently when they are in a larger group, surrounded by others.’

I had a keen sense of observation and was not shy to tell people what I thought, or, more to the point, what they needed to be thinking. I certainly had no reservations about bossing my family around. To my grandmother Lilly, at age 4: ‘You are treating me like a girl, but I’m a boy. You can’t properly educate me this way.’ On another occasion, more directly: ‘Omi, if you want me to listen to you and to have more respect for you, you do sometimes have to slap me in the face.’ To Annie: ‘You know, people in our family are different and each one has his problems: my problem is that I don’t eat much. Omi has the problem that she’s always scared and accepts everything I do—she has to learn how to be stricter with me. Daddy has the problem that he sits on the toilet for too long, sometimes for a whole hour. But you Annie, you have no problems, you are not worried about anything. All of us should be like you!’

With visible concern, when I was 6, I said to Annie (who was about 53 at this time), after she had moved into a new apartment in the Calle Maipú in Olivos: ‘Your apartment is nice, but your bedroom is much too small. What will you do if you have many children?’

To my parents, while they were discussing what to offer Annie for her 54th birthday: ‘Why don’t you give her a book? I’ve noticed that she often reads the newspaper. I’m quite convinced that she’s able to finish a whole book!’ To my parents, on my 5th birthday: ‘These slippers in gold I received, they must come from Annie. She always has such weird ideas.’

To my grandmother Lilly: ‘I am child, Mami is older and you are old. When I’m older, Mami will be old. And by then, you’ll be gone.’ At the table, to my mother, who was upset that my serviette had gotten so dirty: ‘But Mami, what do we need serviettes for if we don’t dirty them?’ To my father, at age 5, after he had scolded me for something I had (again) not done properly: ‘Daddy, people don’t change quickly, why do you expect me to be any different?’ To Annie, after she’s taken me to Harrod’s to see Father Christmas in December 1961, when I was four: ‘Father Christmas isn’t really an old man. He just puts on a bushy beard to appear older when we go to visit him.’

To Annie, who has gained some weight: ‘Annie, are you sure that you’re not expecting a baby?’ Also to Annie, after she had been reading a long story to me and after she indicated that she’d like to take a rest: ‘Annie, you can only rest when your voice is completely gone. Remember that reading to me is one of your responsibilities!’

I had a definite sense of humour and then, as now, had no problems telling stories. Very often during my childhood, I poked fun at my paternal grandparents, who I knew were especially gullible. To Lilly, when I was 5, I said on the phone: ‘You know, the painters came, they’ve done it all wrong, now they need to start again from scratch. It’s going to take two more years until they’re finished! And today, Mom served me old donkey meat!’ (upon which Lilly called Annie, related what she had heard, with the comment: ‘I believed his story about the painters, but I began to be a little less sure about whether he was making fun of me, when he started speaking about the donkey meat!’).

To Szigo, with a professorial tone, also at age 5: ‘You know, when the dollar rises, then there are no problems. But if the dollar falls, then Argentina will go to war. And then there will be another world war.’ To this my grandfather, puzzled, responded: ‘But where do you have this information from?’ ‘I suspect it,’ I said, and hung up, leaving Sizgo quite perplexed.

Or to Annie, after a large meal: ‘If you have too much food in your stomach, then the stomach can’t keep it. It sends it to the heart, which then pumps it into the bloodstream.’ To this Annie responded: ‘But where did you get this from?’ ‘I just invented it,’ I said, ‘like Mozart!’.

At an early age, I knew what I wanted. To Annie’s question, when I was 5, if I had thought about what I wanted to become when I grew older, I responded: ‘I’d like to become a pilot, so I can see the world.’ Then, after a short silence: ‘No, not a pilot, a co-pilot. This way I can still see the world, but I’ll need to work less.’

At age 6, I saw no reason why destiny should determine who my mother was and so one evening said to Ellen Ruhemann, a friend of Paul and Lisl, in front of them and her husband, Peter Ruhemann: ‘Ellen, I would prefer for you to be my mother. Can you be my mother?’

My first trip to Europe took place in 1961, when I was four. My parents were wildly excited. It would be an opportunity to show to me where the family had come from. For my father, it was also a moment of deep gratification, since travel was very expensive in those days, and traveling for a month throughout Europe confirmed to him and to his entourage, that we were materially well off (which we were).

I was less impressed by the trip than Paul and Lisl had hoped. After a few stops in London, Amsterdam and (of course) Vienna, my ecstatic parents dragged me up a steep hill in Tirol. The weather was wonderful. Breathing in the fresh mountain air, and in total admiration of the grandiose landscape, my father said: ‘Peter, aren’t these mountains amazing?’ to which I responded: ‘For you and Mom these mountains are incredible, but I’m a child and what interests me are toys.’

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko