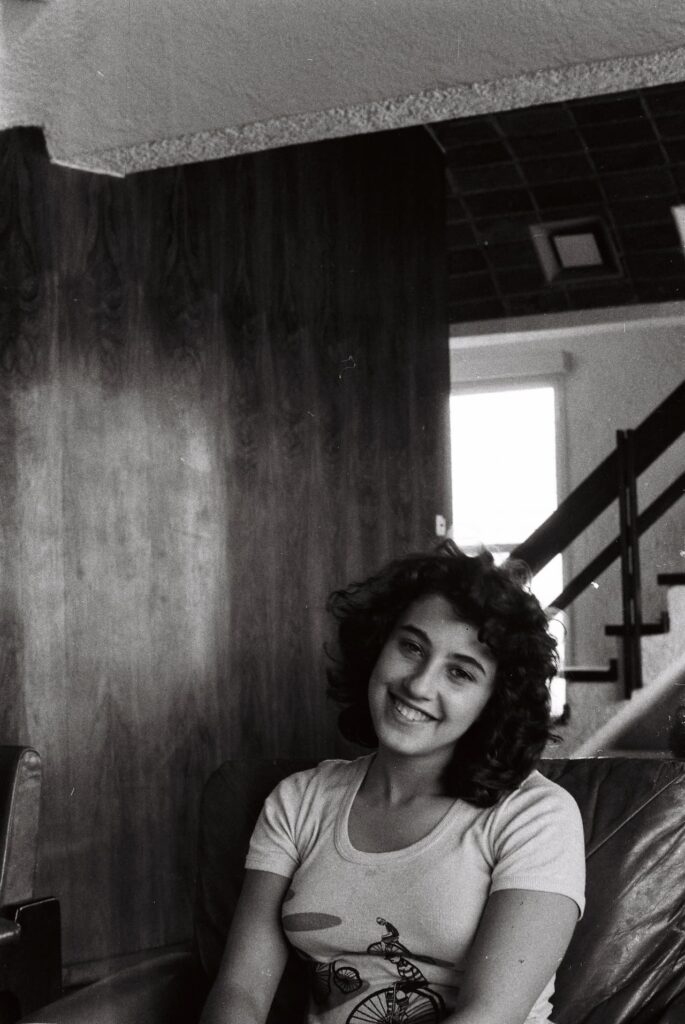

Some of the people who often came to my home during 1973 and 1974 were subsequently abducted, imprisoned and killed between 1976 to 1983, when a military junta ran Argentina with an iron fist. Very prominent amongst them was my friend Miriam Lewin, who was tortured and held in solitary confinement for several years. After her release in the early 1980s, she became a journalist and wrote several books on her experience during incarceration (among them, the most harrowing is Putas y Guerrilleras). Miriam subsequently gave evidence in front of the commission established after the return to democracy in Argentina, and through her testimony helped convict a number of military leaders.

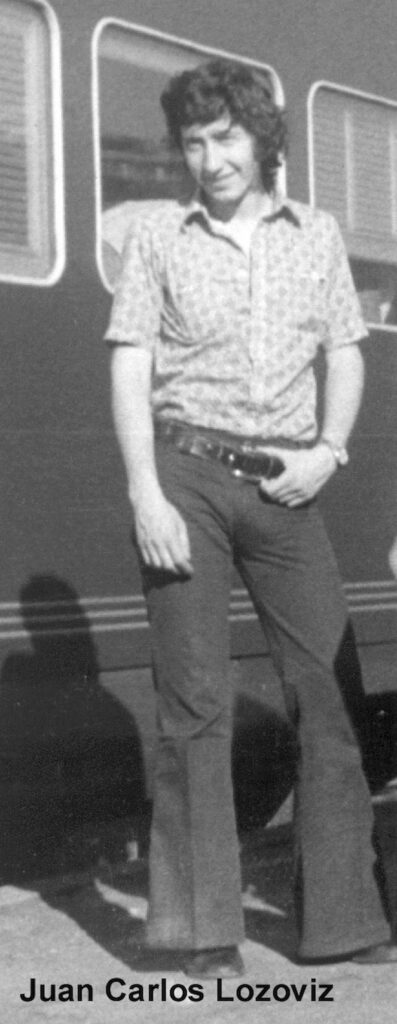

Other friends and frequent visitors to my home included Patricia Palazuelos and Juan Carlos Losoviz, both killed by the junta in the late 1970s. The story of Juan Carlos is particularly tragic: he lived with his mother in a tiny apartment in the centre of Buenos Aires. He was her only son and her passion in life. In September 1977, in the middle of the night, armed men burst into their home and took Juan Carlos away. From then on, and for decades thereafter, Mrs. Losoviz went from one police station to the next, visited every army barrack and contacted dozens of people in the armed forces. The answer she received was always the same: we have no trace of Juan Carlos.

In fact, kids like Juan Carlos were abducted by paramilitary forces which were under the direct command of the junta leaders. They were transported in unmarked vehicles and kept in secret detention centres. After torturing and keeping them locked up, often for years under gruelling conditions, they were drugged, handcuffed and, still alive, dropped from airplanes over the Atlantic, where their death would leave no trace.

During these terrible years in Argentina at least 30,000 people died in captivity, killed by state terrorism. The military junta hunted down not only members of guerrilla movements such as Montoneros and ERP, but anybody with left-leaning ideas, including journalists, trade union members, writers and even artists. In total, 108 adolescents from El Colegio were killed by the armed forces. The youngest ‘desaparecida’ was Magdalena Gallardo, who was 15 when she was abducted, never to be heard from again.

Hardly any of those who were killed died in action or had any combat experience, let alone owned or knew how to operate arms. The vast majority of those killed were like me or Juan Carlos: young idealists, who thought that a more egalitarian society was desirable and possible in Argentina. I could have been one of the dead.

But I wasn’t in Argentina when all of this happened, I was a student in the US at the time. By regularly reading the international press, I knew what was happening in Argentina, but most people inside the country did not. I remember arriving in Buenos Aires during my regular visits home and telling Paul about the persecutions and the disappeared. My father brushed my comments aside and said that I was being influenced by an ‘international campaign of misinformation’, orchestrated by ‘foreign powers’. He didn’t care to see evidence. In fact, he was quite upset that I wasn’t defending the military, who were in his eyes ‘protecting Argentina against armed left-wing subversives’.

Paul’s attitude left a lasting impression on me. It wouldn’t be the last time that he would support actions by governments or individuals who blatantly disregarded human rights. It’s been a shock to me that my own father, an otherwise incredibly good and ethical man, on more than one occasion supported thugs and criminals. My only explanation is that Paul always believed that the means justified the end and that therefore ‘getting rid of socialism’ somehow justified collateral damage, such as a few perhaps ‘excessive’ detentions and killings. ‘You cannot get rid of these socialists and communists without a heavy hand’, he used to say. His thinking has always been that ‘you have to take sides’. I have never thought this way and the few differences I’ve had with my father have nearly always revolved around issues such as these.

In the area of politics, Lisl was much more nuanced. She always showed sympathy for those who were not well off. Whereas my father thought that the poor were not well off because they didn’t work hard enough, Lisl believed that not everyone grew up with the same level of opportunities. She regularly contributed to charities and helped out in areas of Buenos Aires where she knew that people in need lived. Even though she thought that capitalism was a much better system than socialism, she understood that it was far from perfect and that more needed to be done to protect those who were disadvantaged. I owe to her my lifetime empathy for those who are less well off, and my belief in a more equal society.

Political activity was part of everyone’s life at El Colegio, but it wasn’t all we did or spoke about. We were adolescents, and sexuality and love were of course part of our lives. We were strongly influenced by the rest of the world, in particular the ideals of the hippie and anti-war movement in the US, and even more so, by the 1968 Paris Spring student uprising. We studied Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, read the liberation theology of Dom Hélder Câmara, the philosophy of Erich Fromm and the plays of Bertold Brecht. Free love was in the air, and our sexual lives were totally uninhibited. Because there was little stigma attached to sexuality, because it was considered natural and not a big deal, it didn’t occupy centre stage in our lives. Most of the time we drifted together in large groups, and our relationships with the other sex were platonic.

During my adolescent years, phones were totally unreliable or simply didn’t work, and because I lived so far away from the centre of Buenos Aires, it was very difficult to communicate with my friends. Nora and I were very close, but we only saw each other periodically because she was younger and in a different class at El Colegio, so we would exchange handwritten notes, which we deposited in a large tree in the Parque Lezama. I can still remember the excitement of arriving at the park and scanning an old ombú (nuestro árbol, our tree), until I saw a white piece of paper, folded many times over, waiting for me. I have kept many of Nora’s wonderful little messages, filled with wit, love and friendship.

The strong sexual hang-ups and tensions I later witnessed as an undergraduate student in the US, were totally absent during my high school years. The same can be said about alcohol and drugs: there were none during my time in El Colegio. Because I lived in a society in which there were no barriers to alcohol consumption, few adolescents consumed any spirits. In fact, I cannot remember attending a single get-together during my high school years where alcohol was present. And drugs were simply unheard of.

To me or to my friends, material goods were of no significance. No one paid much attention to clothes, we usually put on whatever we had at hand, and often wore the same clothes for many days. Excessive attention to how you looked was considered a sign of bourgeois decadence and frowned upon. Perhaps owning a musical instrument was of value, but even that was usually shared (my friends would often take my guitar and return it days or weeks later). It was an environment of ideas and ideals, not one of material possessions. The people who we admired were those who could speak eloquently, sing well, were witty or read interesting things. This might explain why, to this day, I have such an allergy towards shopping.

As 1974 drew to a close, Argentina was rapidly heading towards political chaos and my parents became increasingly worried that I would be dragged into one of the many ‘extremist’ movements. At the same time, I had had enough of living at home, was in a rebellious mood, and my relationship with Paul and Lisl had become very tense. When El Colegio unexpectedly announced that in 1974 students would graduate after 5 years of high school (and not 6, as had been the case until then), Annie, who was watching the escalation at home with increasing concern, had a brilliant idea: ‘Why don’t you spend some time abroad?’ she asked me in August of that year. ‘How about a year in Europe? You’ll be graduating in a few months, at barely 17. You can afford to take some time off’, she said.

I immediately liked the idea. At the time, my parents were in Europe and so Annie helped me draft a letter in which I argued my case. Annie knew that Paul would never allow me to just ‘hang out’ in Europe, so she had the idea of labelling the experience as ‘a year to improve my language skills’, something she knew the very practical Paul would like.

Indeed, my father was seduced by the prospect of a year abroad for me, and overrode my mother, who was concerned that I was too young for such an experience. I began to speak to my friends about my plans and soon Fernando Vidal, who was graduating from El Colegio at the same time, decided to join me.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko