In yet another reshuffling of the military leadership, in 1971 Alejandro Lanusse had become President of Argentina. Faced with continuous political unrest and an increase of guerrilla activity, Lanusse decided to organise elections for March of 1973. For the first time since 1955, Perón’s party was allowed to participate (although not Perón himself; it was only later that he would once again become President of Argentina). The elections were free and open and the months leading up to them generated a degree of political effervescence that had not existed in Argentina for decades.

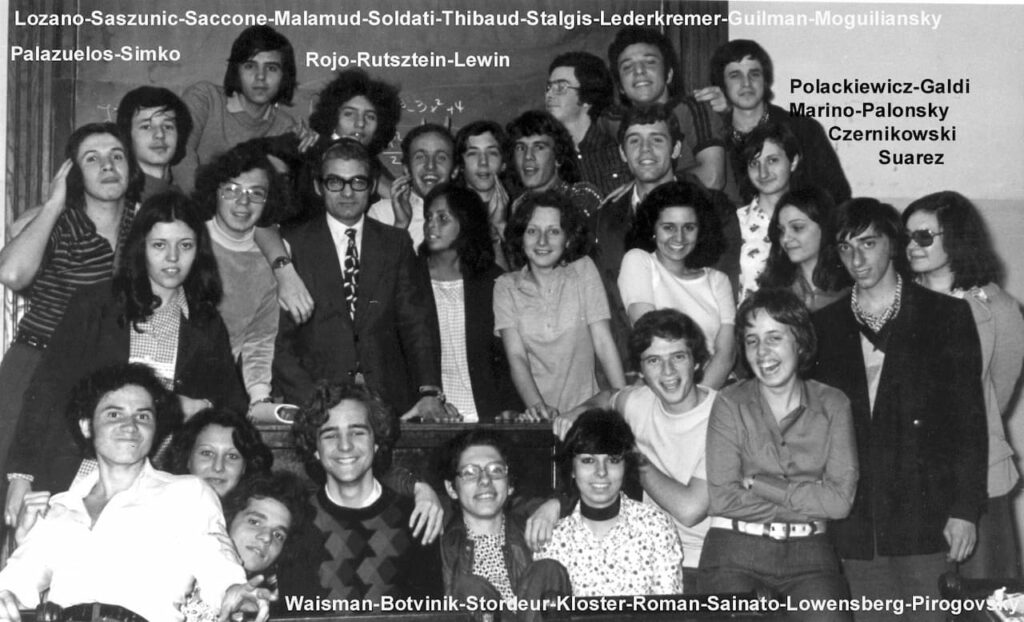

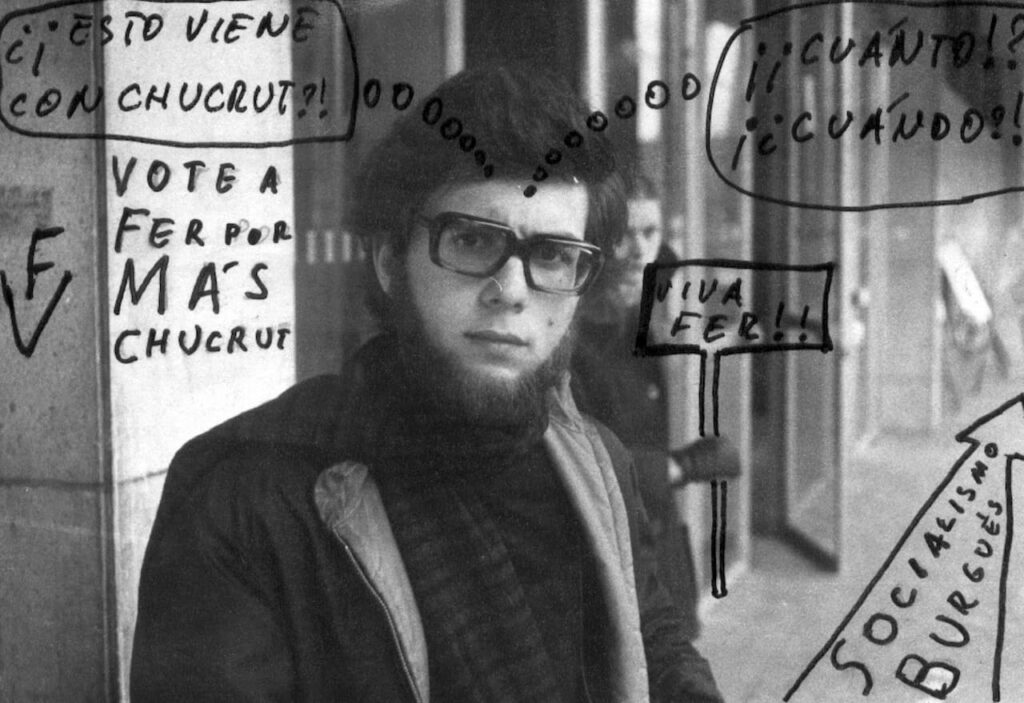

In my very militant school no less than 23 political parties sprung up in a matter of a few months, and started to compete for the attention of the students. All of them, without exception, were to the left. There were the Trotskyists (TERS – Tendencia Estudiantil Revolucionaria Socialista), those who supported the Soviet Union (FJC—Federación Juvenil Comunista), the fans of Cuba (JG—Juventud Guevarista), as well as a sizeable group of Peronist groupings (UES—Unión de Estudiantes Secundarios; JP—Juventud Peronista; FES—Frente Estudiantil Nacional; JUP—Juventud Universitaria Peronista; FLS—Frente de Lucha de los Secundarios and JTP—Juventud de Trabajadores Peronistas). Some of the largest organisations were those representing guerrilla groups: ERP—Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo; FAR—Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias; FAL—Frente Argentino de Liberación, and the largest of them all, Montoneros.

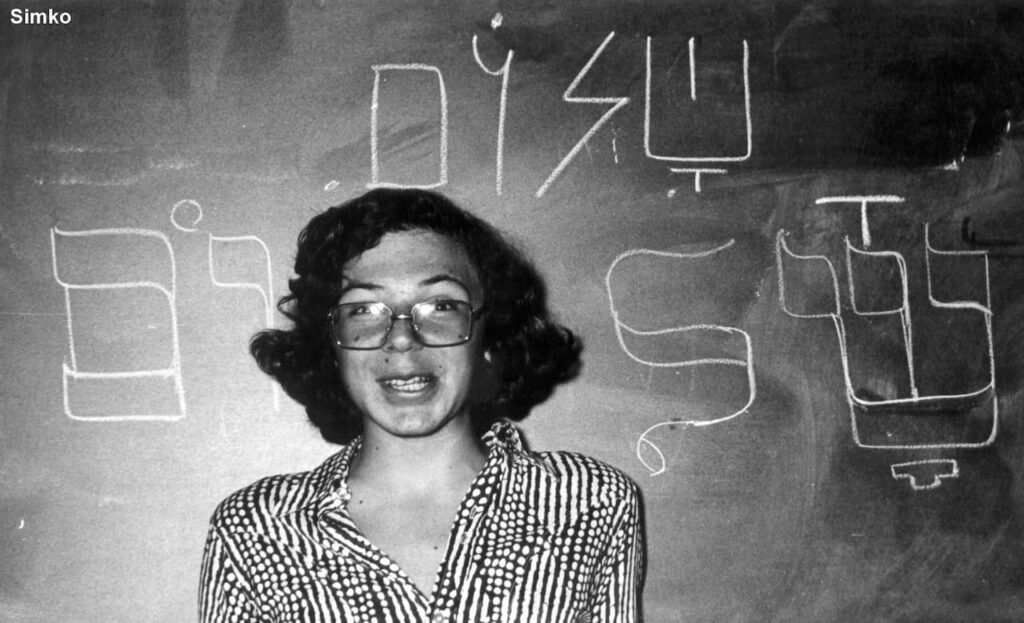

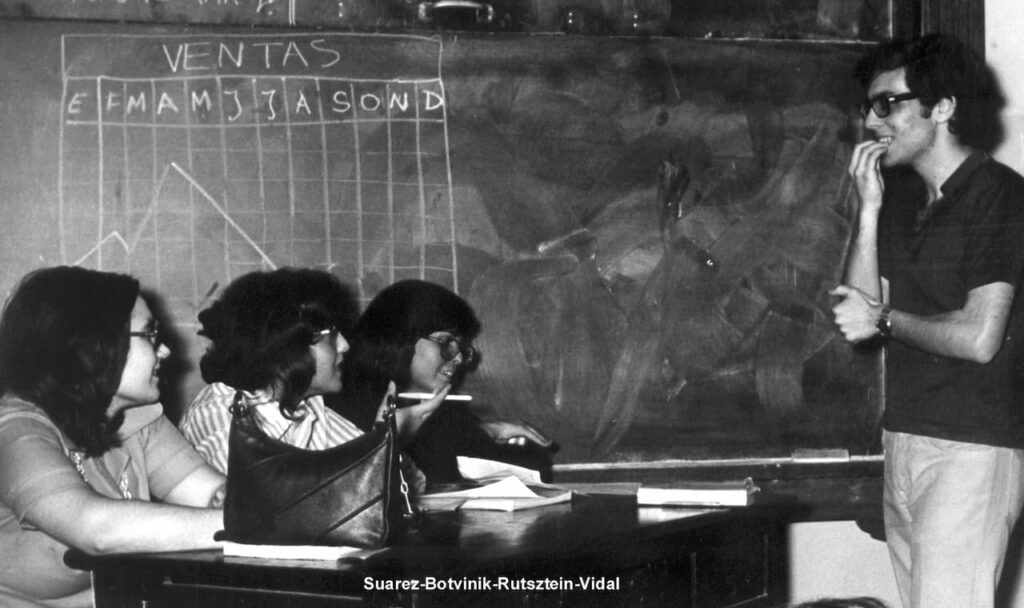

Step-by-step, formal classroom teaching was reduced, replaced by sit-ins, debates and discussion groups, mostly led by students, but sometimes also by professors, on how best to participate in the incipient political and cultural revolution in Argentina. The school walls, which had always been immaculately clean, overnight became covered by political statements from the various groups. Soon no space was left uncovered, not even in the toilets.

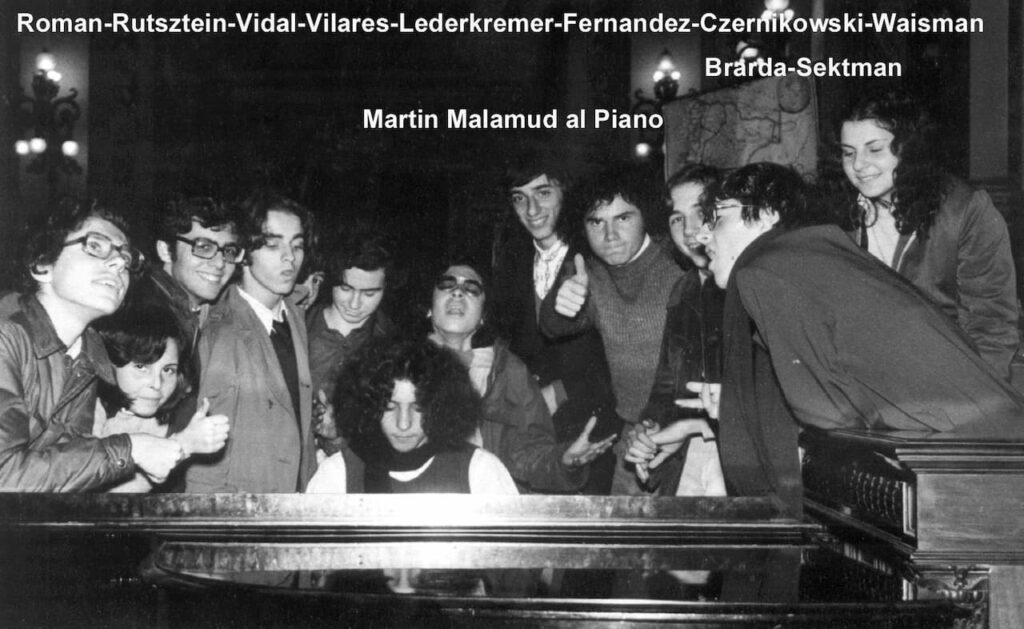

Raúl Aragón, the newly appointed director, encouraged political militancy and frequently participated in the discussion groups himself. He did away with hierarchy and asked students to address him as ‘Raúl’. He launched workshops where students were encouraged to provide input on how best to revitalise secondary education in Argentina, as well as to imagine how secondary students could contribute to a better society. Aragón had the school’s top floor rearranged and transformed into the SUM (Salón de Usos Múltiples), where we could listen and play music. It included ping pong tables and large open spaces, where all forms of art were encouraged.

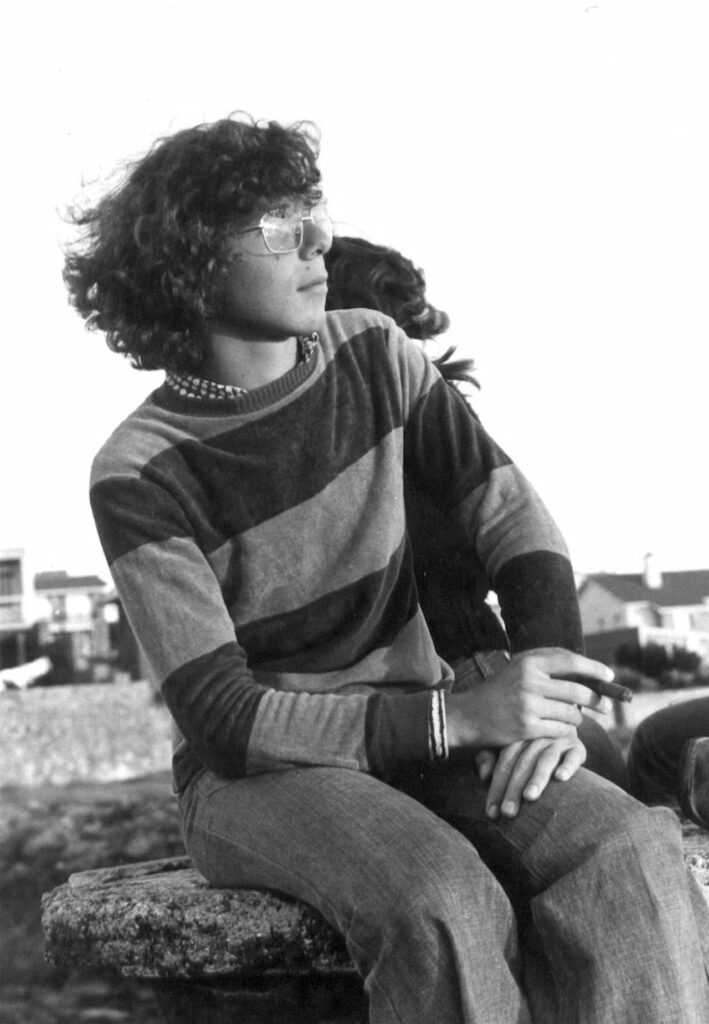

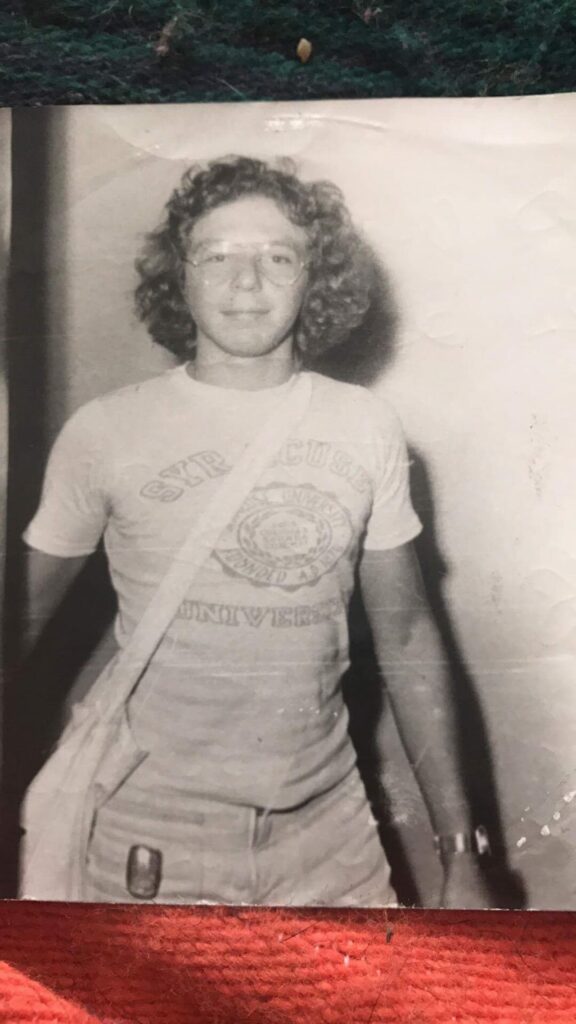

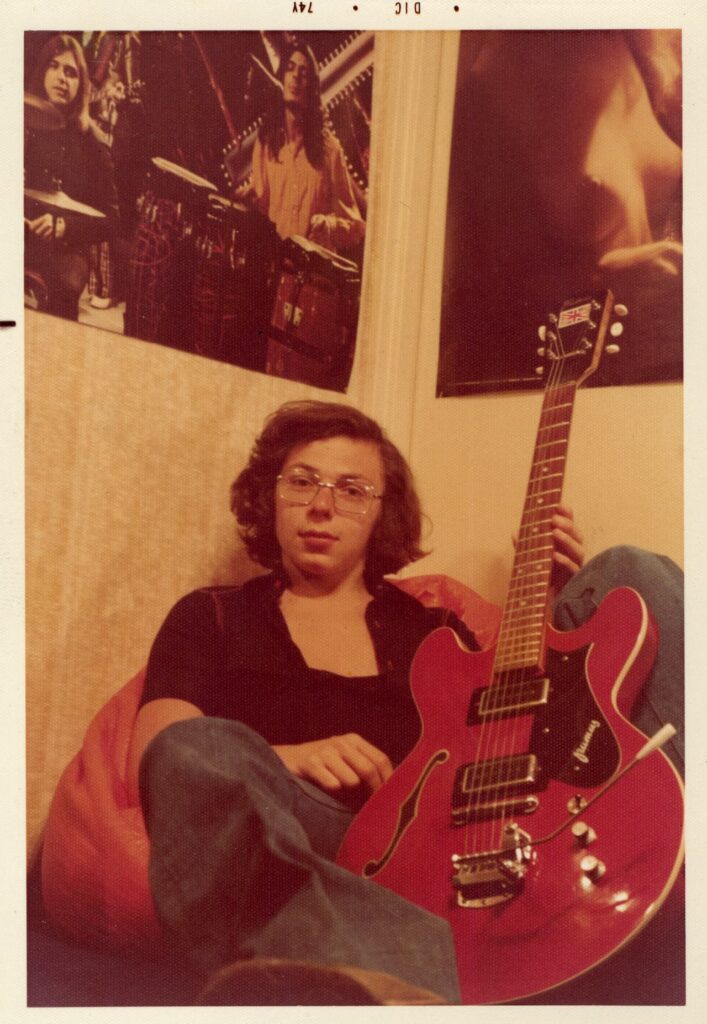

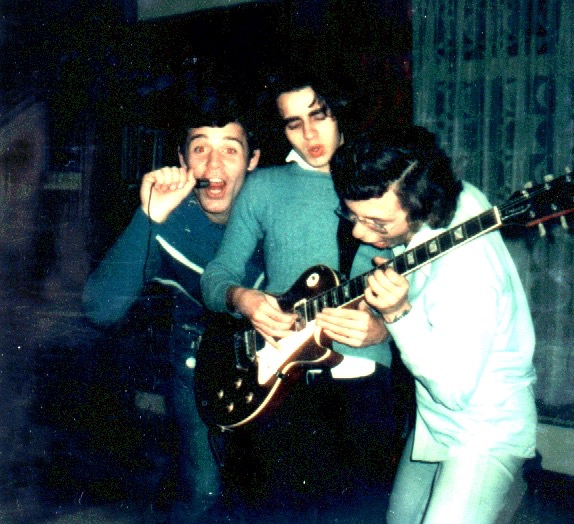

What had been a very formal and traditional school, with compulsory grey and dark blue uniforms, ties for boys and skirts for girls, became a jeans and t-shirt environment. To the horror of my parents, my hair started to grow and from 1973 onwards, I no longer carried books to school. I left home every day with my guitar. In an inside pocket, I carried a little notebook and coloured pencils. I spent my time at school attending meetings, reading poetry and, especially, playing music and singing songs with my classmates. We fraternised with the professors, several of whom subsequently became lifetime friends. After school, I took guitar lessons and played loud music, to the consternation of my parents.

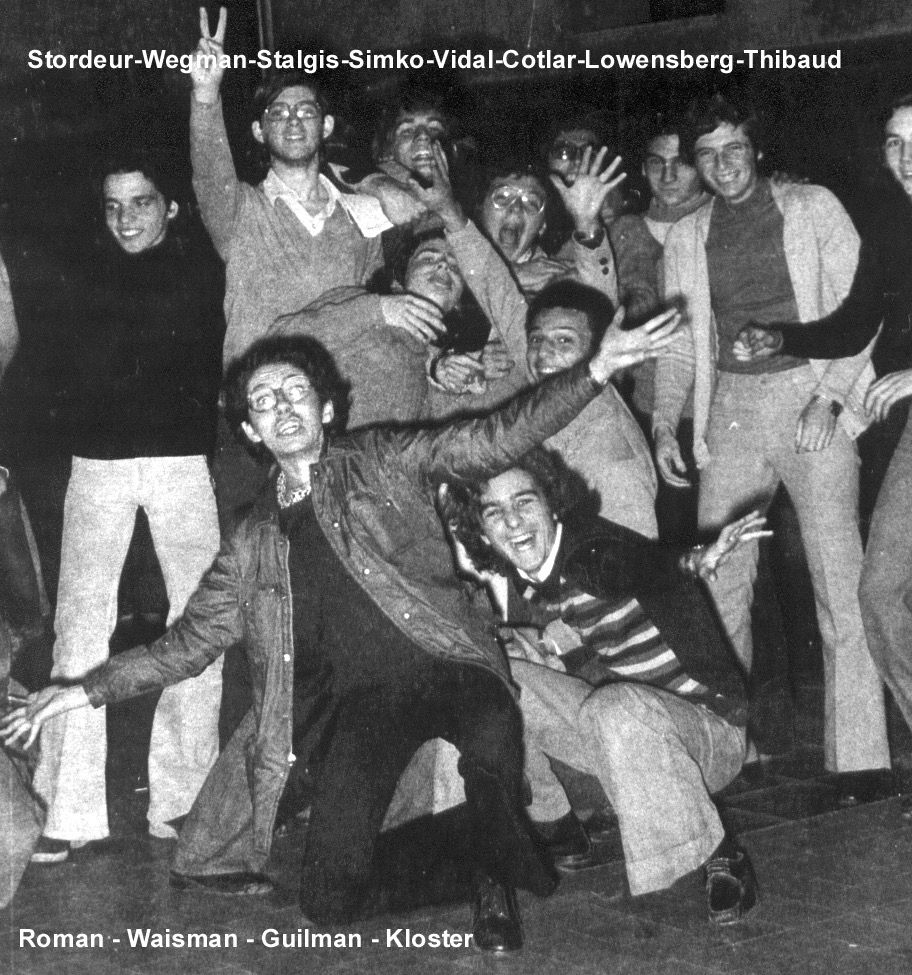

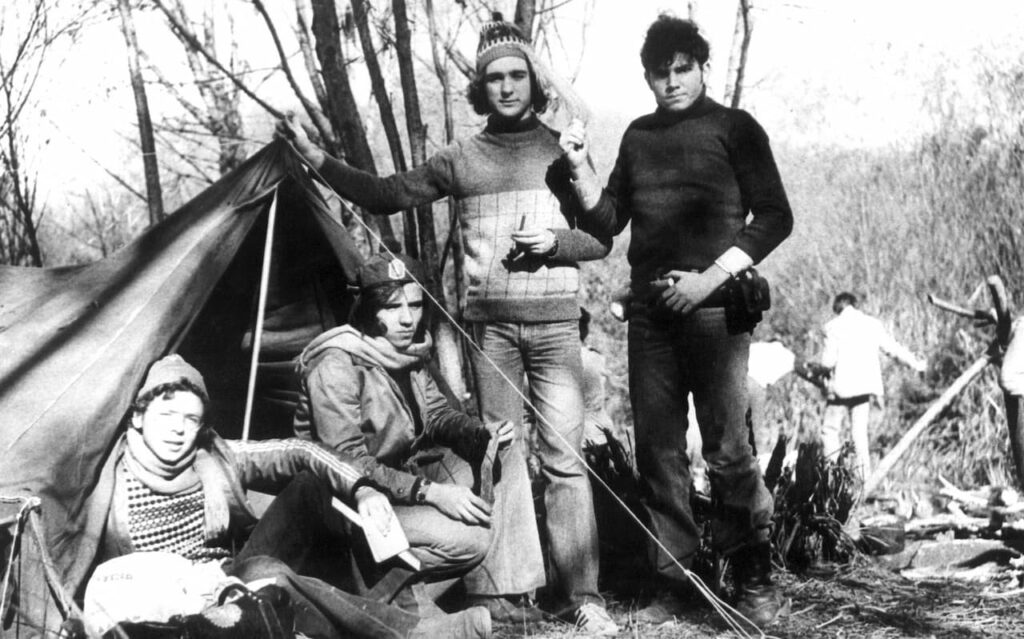

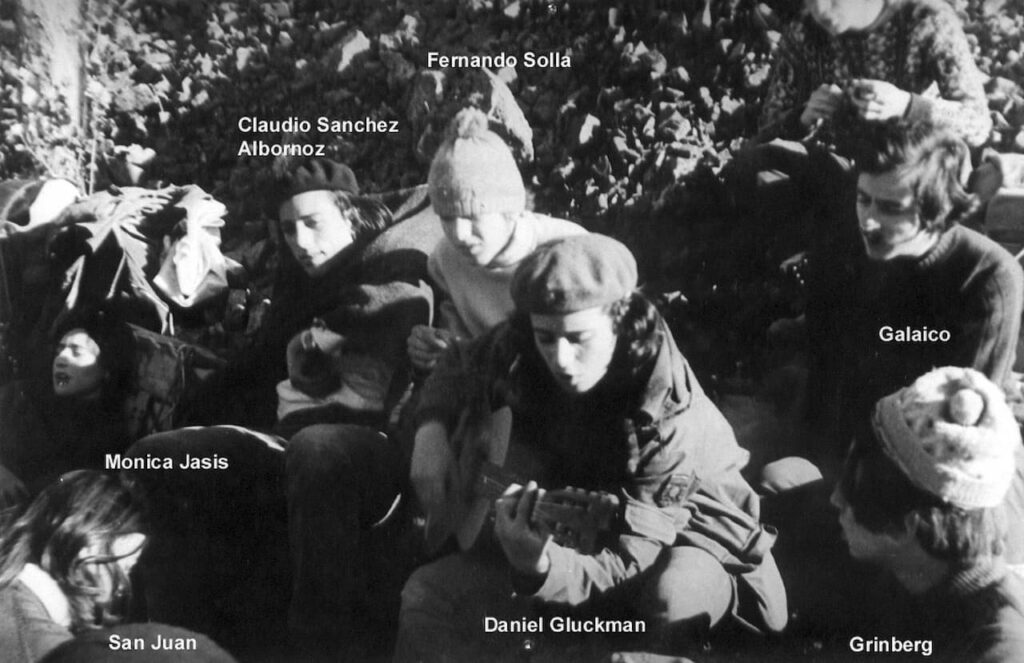

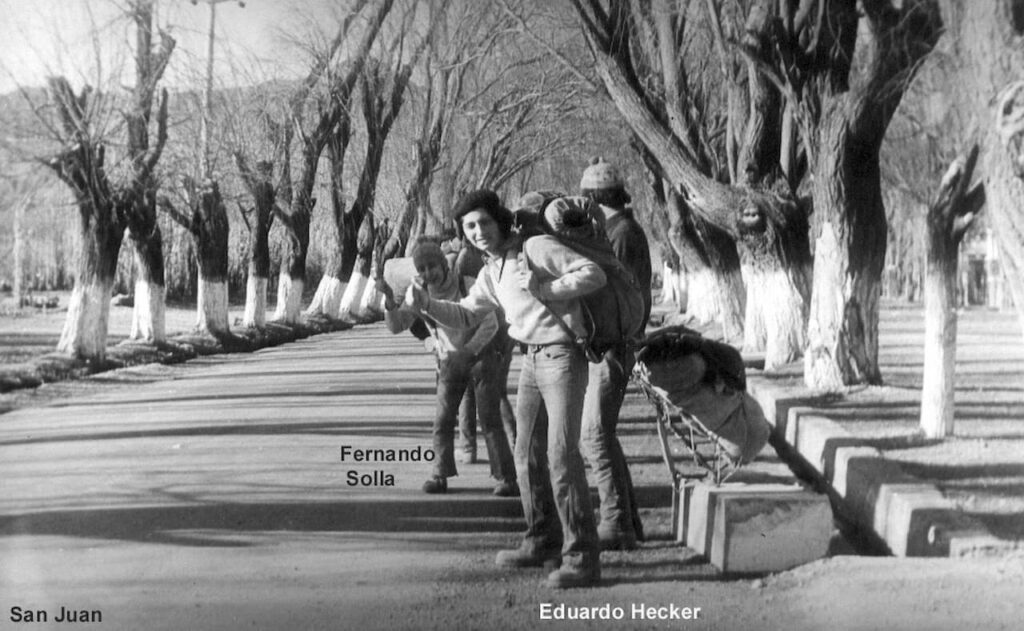

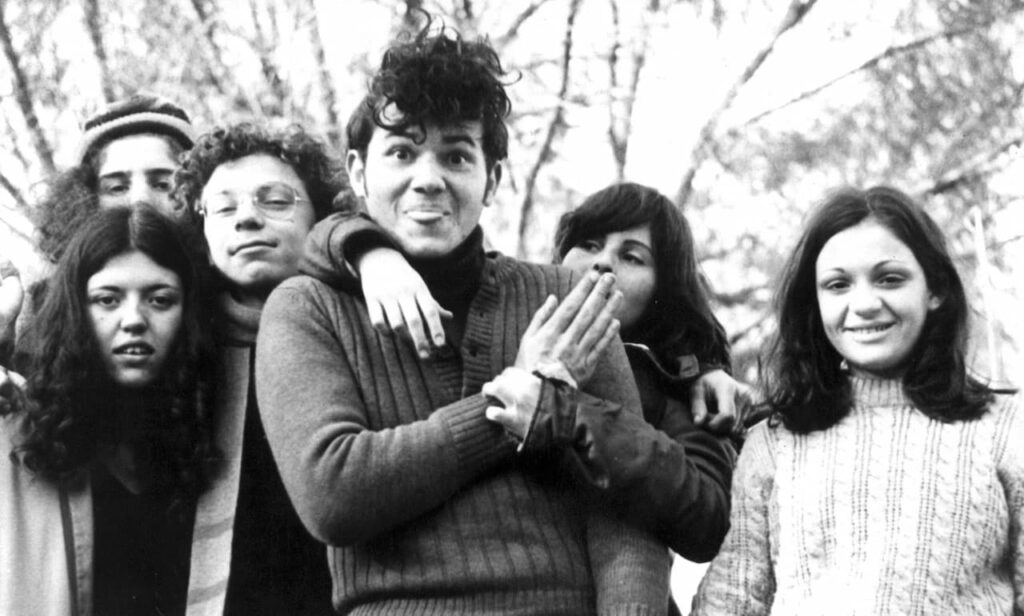

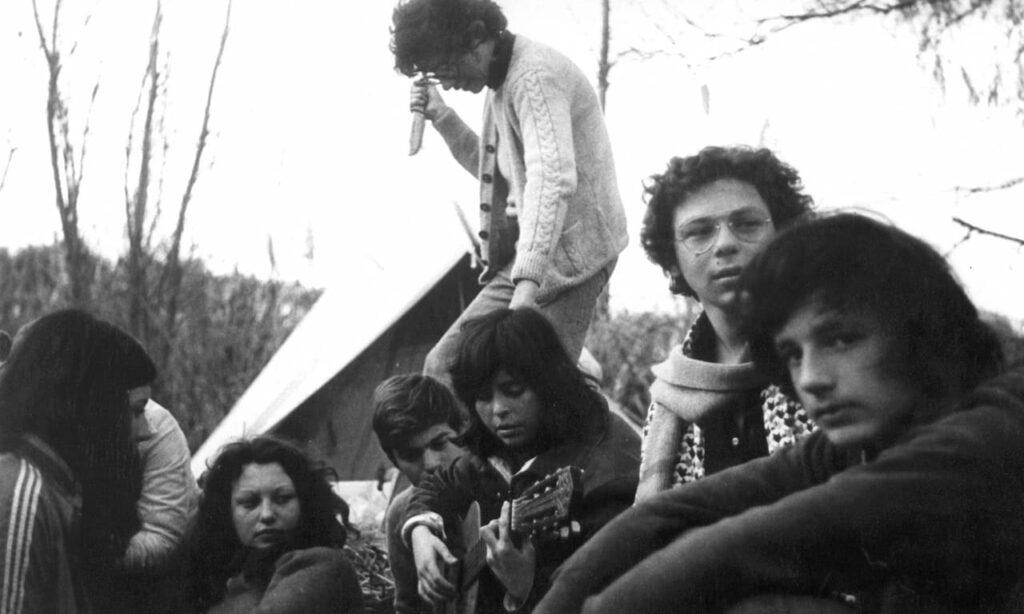

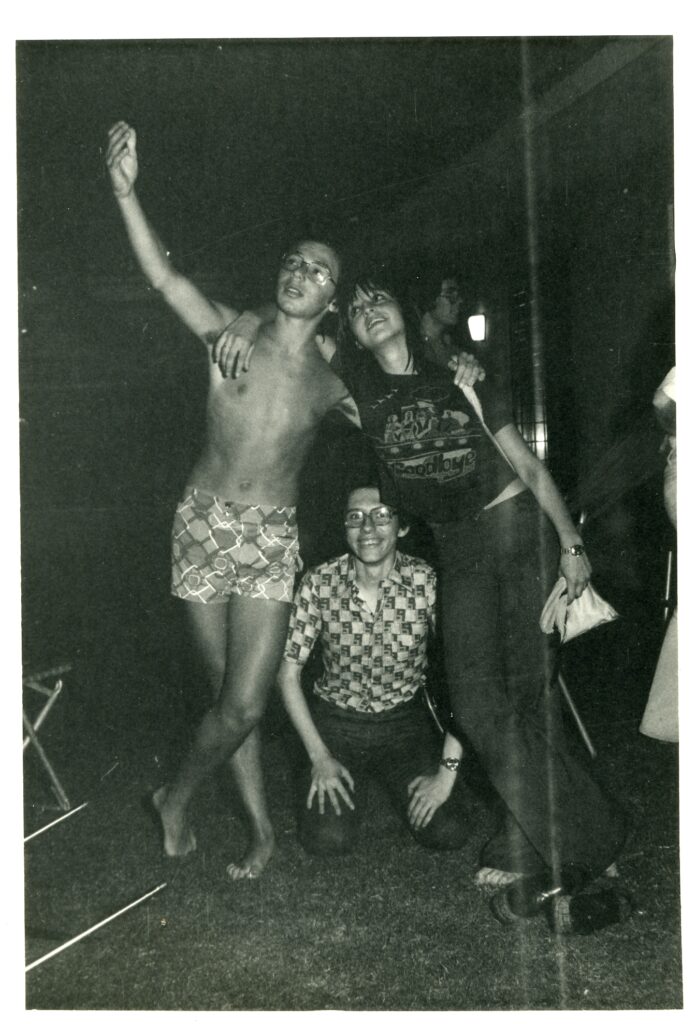

With few formal classes and revolutionary activity taking up only a part of our day, there was plenty of time left for get-togethers and parties, many of them quite inventive. To better gain an understanding of ‘the proletariat’, my friends and I frequently visited parts of Buenos Aires where the poor people lived and helped with whatever tasks were required, like building houses or painting buildings. To ‘get closer to nature’, camping trips were organised in the Province of Buenos Aires, where we were often accompanied by our professors, now comrades-in-revolution.

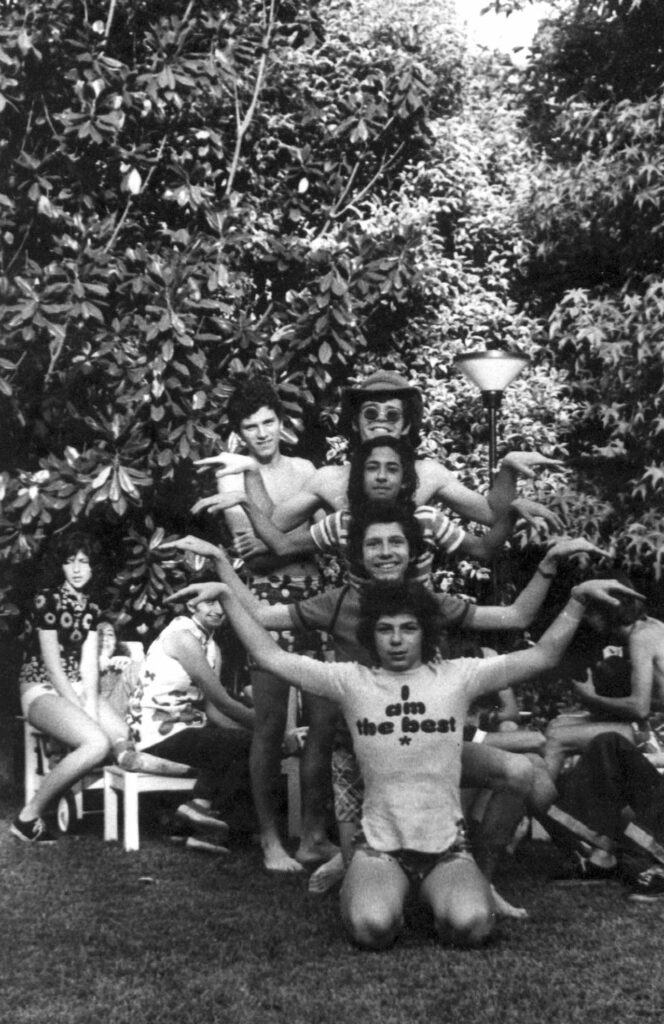

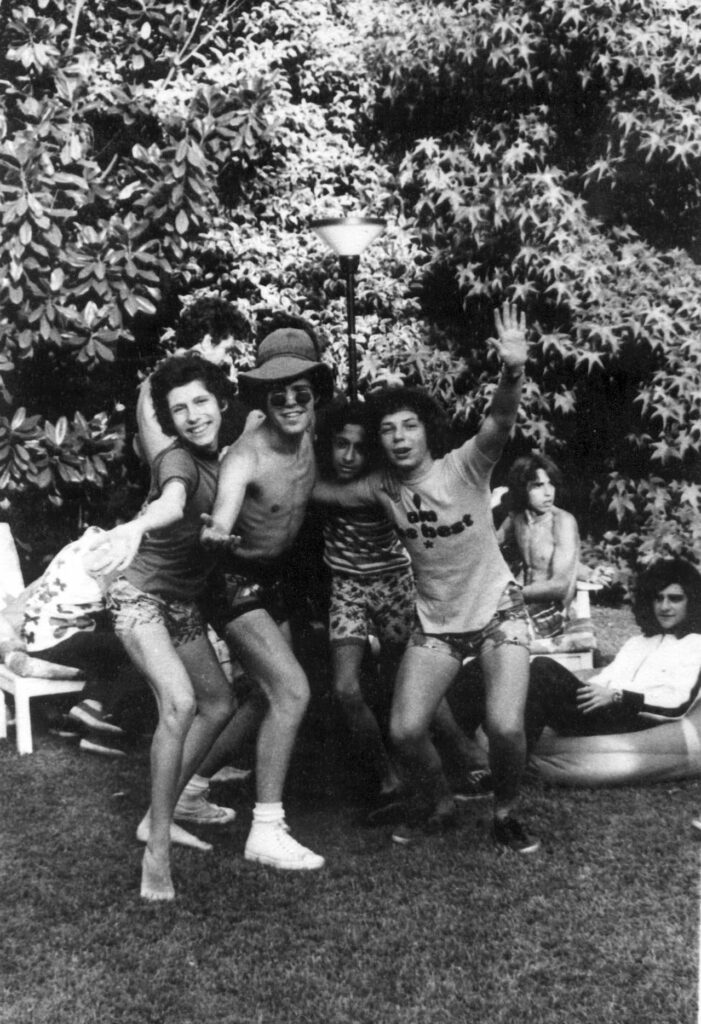

Very regularly, my friends would show up at my home and spend the weekend there. In the beginning, I was a bit worried—what would my revolutionary friends think of my very bourgeois home? But I soon realised that the El Colegio crowd were quite pleased to get together in such a large garden and, especially, to be able to jump into a swimming pool in the hotter months of the year. Plus, my mother was very welcoming. She loved to have people around, so every time ‘los compañeros’ showed up, she quickly put together a few Austrian dishes, to the delight of my friends.

At the time, the telephone system didn’t really work in Buenos Aires, and my home was far away from the Capital Federal, where almost everyone else lived, so people would just pack their stuff and show up. On many weekends, our home resembled a railway station, with people coming in and out at all hours of the day and night.

My father accepted these large crowds, but had more problems with the long hair, and especially the socialist, if not outright communist views of my friends. I sometimes worried that some of the people who had showed up in those years, and who later became prominent in Argentina’s guerrilla movements of the mid-1970’s, would remember Paul’s very capitalist views, and plan an attack, but nothing ever happened. I guess that many of those who came to my home in the years 1972 to 1974, preferred to remember (and were grateful) for the long evenings, the music, the pool and the wonderful food, and didn’t focus on my father’s political views

In 1973, Paul tried to introduce me to golf. His argument was that ‘what you learn at a young age, stays with you’ and that ‘golf is good to make business relations’, arguments which made little sense to me at the time, especially given the context of what I was experiencing at school. I did, however, accompany my father a few times to the golf course. It was a short-lived experience, but nevertheless I did learn the rudiments of a golf swing, which would come in handy to me many years later, when I lived in England. As on other occasions, my father’s practical mind and foresight, created positive effects in my life, although in this case, it happened much later.

.

As usual, we spent the summer of 1973/74 in Punta del Este. This time, Paul and Lisl rented a house called ‘Tucu Tucu’, which included a large garden. It was great for them, but a nightmare for me—the house was located about 8 km from ‘La Punta’, which meant total isolation from my friends. Luckily, at the time 16-year-olds were allowed to drive in Uruguay and I was able to obtain a licence without much hassle. My parents agreed that I could get a licence and drive the family car, but on one condition: I had to cut my hair. I protested vehemently, but there was no negotiation possible: it was either a car and short hair or long hair and no car. Humiliated, I accepted the haircut, but vowed revenge. I told them that I would forever remember how they had blackmailed me. Indeed, I never forgot this incident, and vowed to myself that as soon as possible, I would leave home. I also promised to myself that if ever I had children, I would never force my will onto them in the way that my parents had. I kept my word.

In June of 1974, while at school, we received a message that President Perón would give a speech from government house, a few blocks away from us. El Colegio was promptly closed and all of us marched to Plaza de Mayo, which was quickly filling with busloads of workers from all over Buenos Aires. As was customary at the time, when El Presidente spoke, all activities ceased and everyone went to listen to him. What none of us knew, was that this would be Perón’s last speech. He died a few days after.

I had never supported Perón, but I was carried away by the frenzy of the crowd and soon, to my amazement, I was singing with everyone else ‘La Marcha Peronista’, the equivalent of the Nazi’s ‘Horst Wessel Lied’. I was struck at how easily I had gotten carried away and had joined a group that I had nothing in common with. This event allowed me to understand group psychology much better than any textbook would. Paul realised quicker than I did what had happened—he had gotten enthralled in a similar way when Hitler arrived in Vienna in 1938. This video gives you a good feeling of the atmosphere in Buenos Aires on this day.

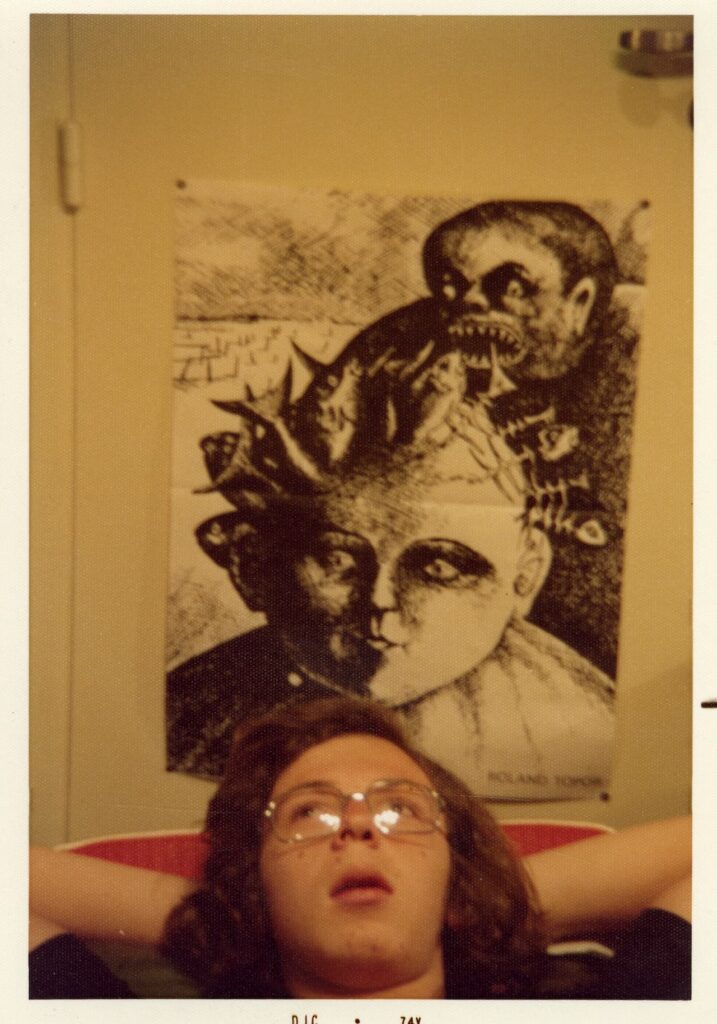

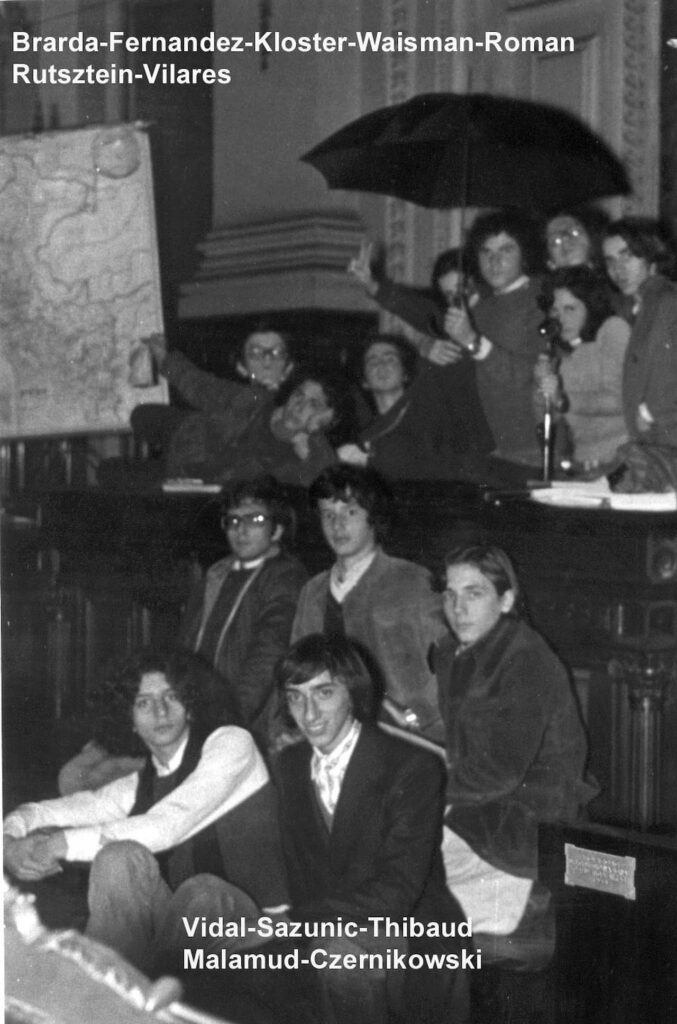

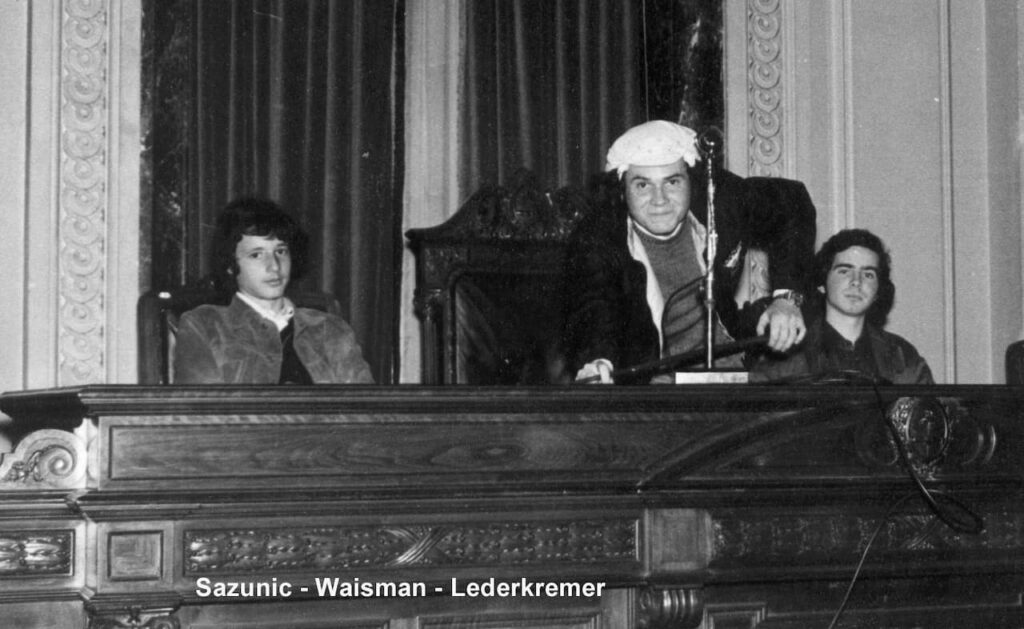

In July of 1974, we occupied El Colegio. Following Perón’s death, we were worried that the new government, led by his wife Isabelita, would take a turn to the right (which it did). The student take-over was justified as a way to defend Raúl Aragón, our director, whom we loved and feared would be cast aside (which he was, but a bit later). The school’s occupation meant that I was now very rarely at home. All classes were suspended following the student occupation (who needs to study math or biology when the nation’s future is at stake?), but there were multiple duties to be performed, which required everyone’s presence. We had to carefully check who came in and out of the building, organise food (in case of a longer siege), organise mattresses (since many of us now lived more or less permanently at the school) and prepare the student body, in case of a ‘fascist attack’. We also needed to read, debate and share widely information on the best way to conduct revolutionary activity.

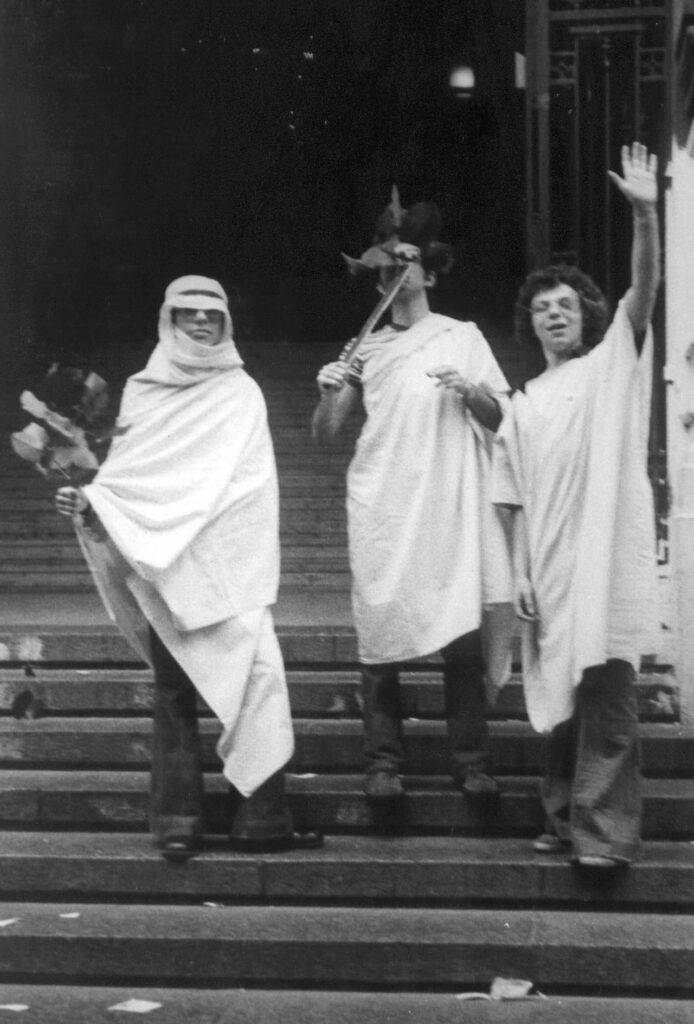

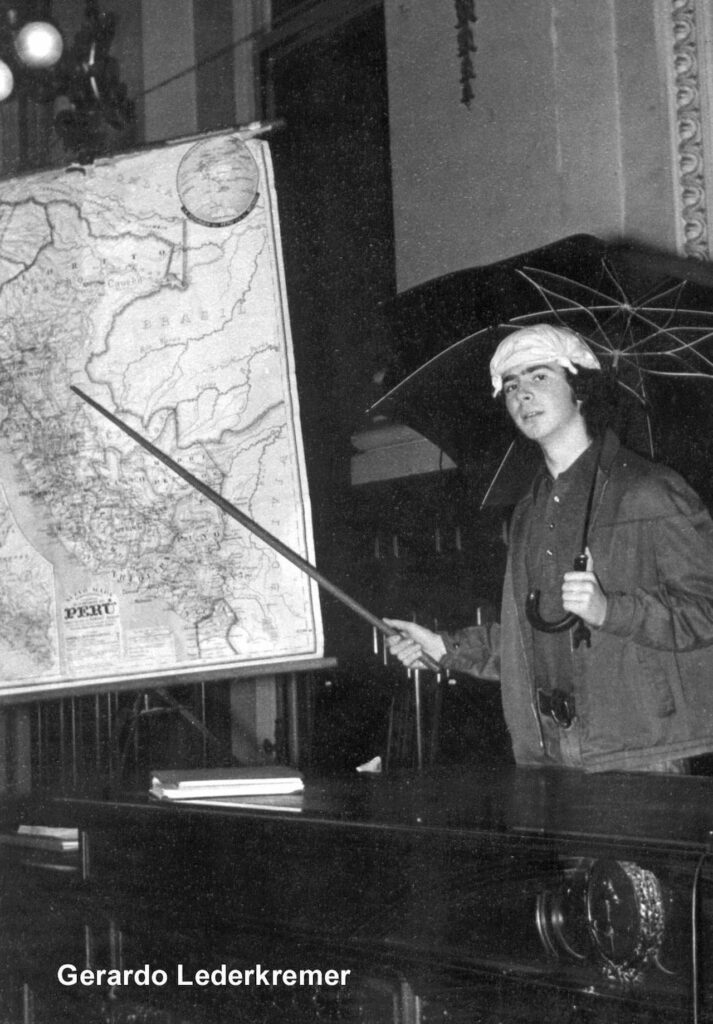

Our guiding lights at the time were the Chinese Cultural Revolution (including Mao’s little red book, which we read religiously) and Che Guevara’s tips on how to nurture a revolution. These very serious tasks did, however, leave sufficient time for music, the screening of a few student-initiated plays, poetry readings (Pablo Neruda was among our favourites, all the more since he had died the year before), and a bit of self-irony amidst the very important business of conducting a student-led insurrection.

The excitement finished after a month, when the entrance doors suddenly burst open and about two dozen soldiers ran into the school, detained us and expedited us in armoured cars to the police station. I was among those who spent the next two nights in detention, a bit longer than my colleagues because, stupidly, I did not have my ID with me at the time when the army arrived. Six or seven of us were thrown into a small and damp cell, and we were barely given anything to eat. But we were not mistreated and were let go following a lengthy sermon about how to become good citizens.

You can imagine the reaction of my parents—especially that of Paul—who was now convinced that I would become a guerrilla and be killed in action. His fear about my future planted a seed in his mind that it might be best for me to spend some time abroad, something that would eventually change the course of my life.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko