So, in early January 1975, Fer and I left for what would be a profound and transformative experience, one which would forever change our lives.

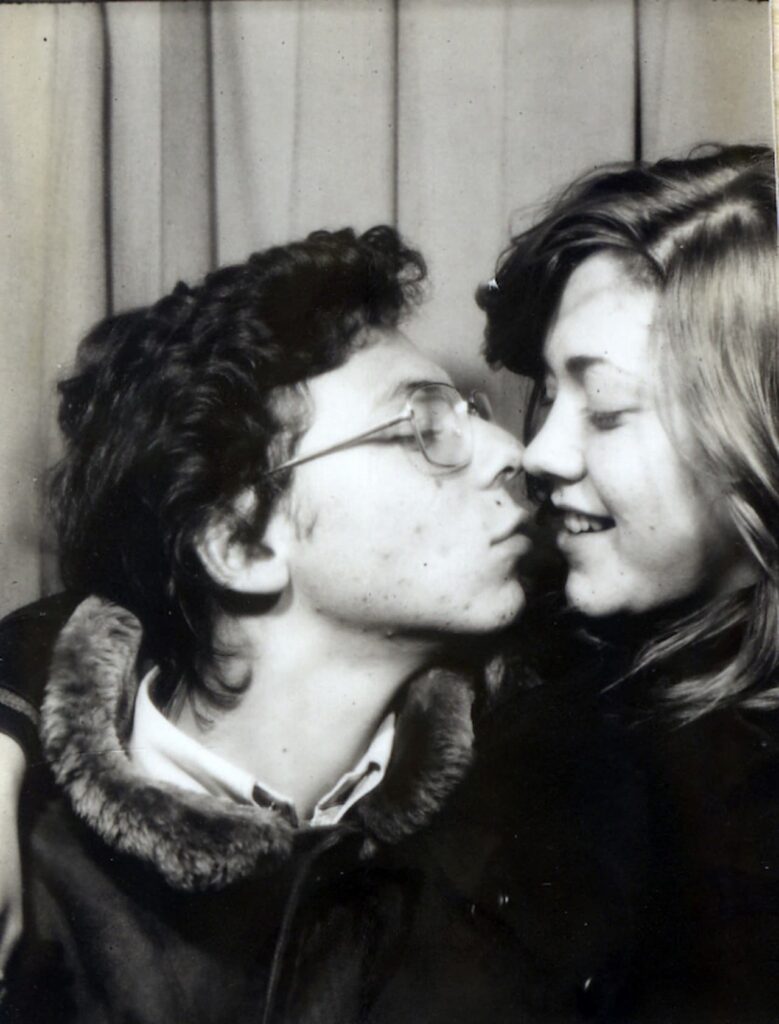

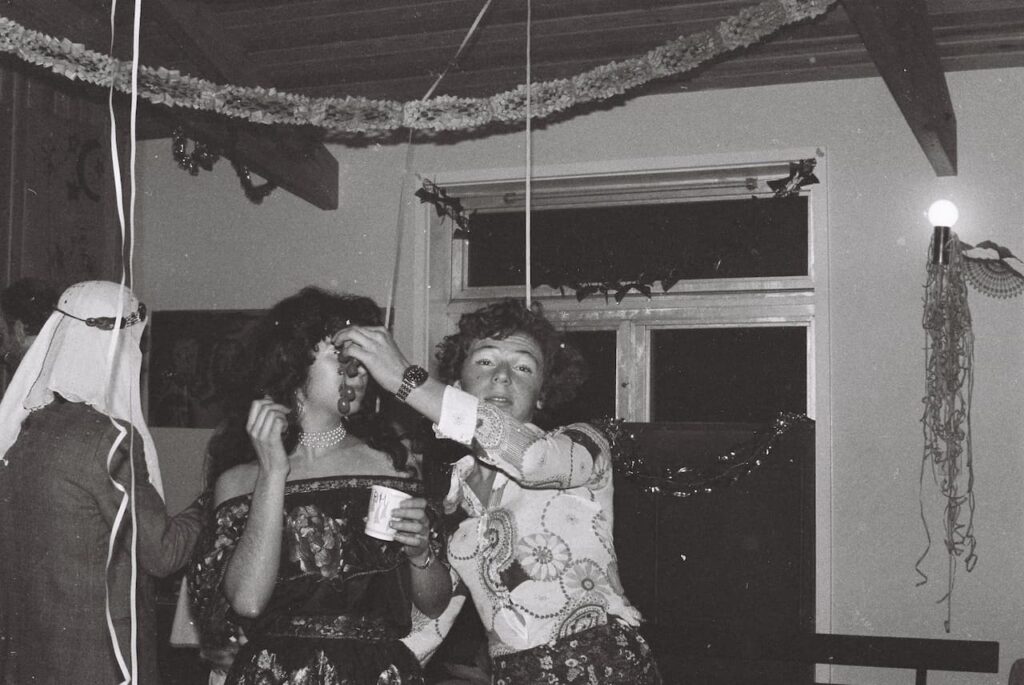

The first stop was the UK, where I was enrolled at the Bell School of Languages. Because English was not taught at El Colegio, Paul, with his usual practical mind, had insisted that I take private lessons to ensure I would not lose what English I had acquired during my elementary school years at St. Andrew’s School. So, during high school, twice a week, I had had a private tutor, who did his work so well that when I arrived at the Bell School, they ranked me in the top section. This meant that I didn’t have to study much and, indeed, I spent most of my three months in Cambridge visiting the UK, going to parties and repeatedly falling in love.

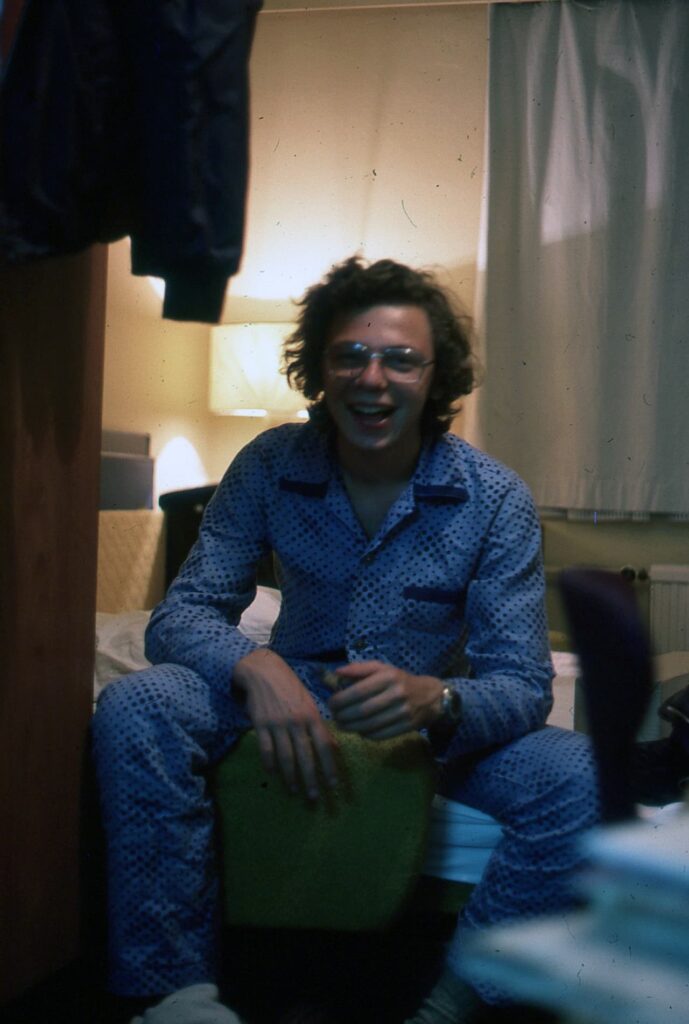

The Bell School of Languages was filled with not always very bright, but uniformly rich kids, who came from all over the world. At 17, I was one of the youngest, but integrated well. The people I met there had no political ideals and had barely heard of Argentina (except that good polo horses came from there). No one had read Romain Rolland or Paul Sartre. But everyone wore fancy clothes, went to the hairdresser often and thought that philosophical discussions were intensely boring. What they loved were parties, getting drunk and spending money on frivolities. The girls were totally uninhibited and forthcoming. It was, to say the least, a totally new experience for me, which I thoroughly enjoyed.

The time in the UK wasn’t only about parties; the school organised cultural trips to London, which I loved, including a memorable concert at the newly opened Royal Festival Hall. I was also introduced to Cambridge University and attended a few classes there, an experience which would later reveal itself as game-changing in my life.

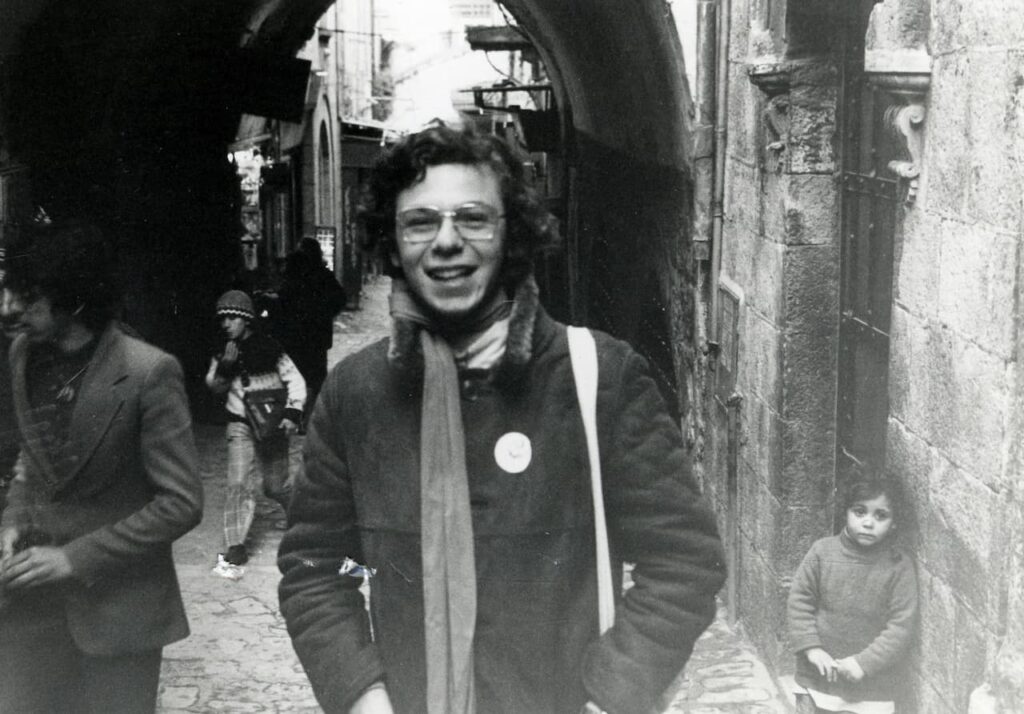

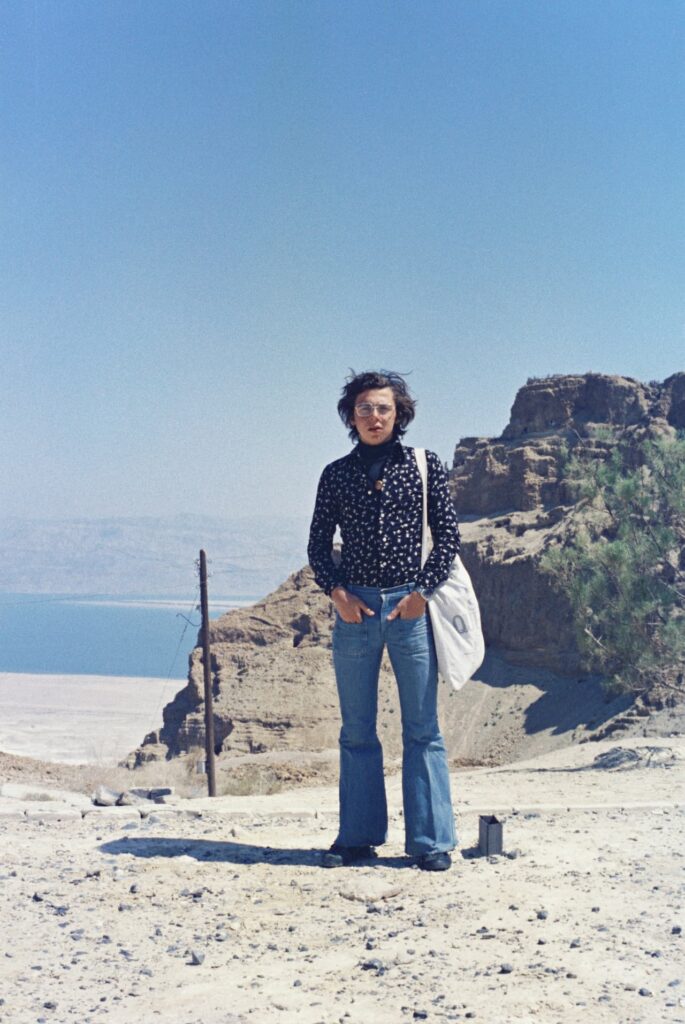

After the UK, I had two weeks off before moving on to Vienna. Paul, worried that I might drift off to somewhere undesirable, arranged for me to spend my time with the Mandlers in Israel. Ernst and Eva Mandler, originally from Austria and good friends of my parents, had emigrated from Argentina to Tel Aviv in the late 1960s. Ernst was a stern man, an idealist, who moved to Israel for emotional reasons, in order to build the nation and ensure that his offspring would settle there. In his view, there was no room in Israel for non-Jews or non-Jewish culture, and I quickly came to feel it when, one afternoon, he caught me listening to Arabic music.

During my year in Europe I travelled lightly: with only a backpack and a small suitcase, but I did carry with me a radio + cassette player. Wherever I was, I listened to the local radio stations and, especially, to music. In Tel Aviv you could easily tune into Jordanian or Palestinian radio channels. I had never heard Arabic music or the language spoken, and was fascinated by it. When Ernst heard Arabic sounds, he burst into my room and asked me to immediately change the channel. I was totally perplexed, and initially gave no signs of obeying, but he firmly and in a loud voice said that ‘no enemy music’ would be tolerated in his home. It was the first time that I was exposed to such narrow-mindedness and cultural bias. This experience, and a few other blatantly racist comments I heard while in Tel Aviv, left with me an image of Israel that was very unsettling.

Fer and I were in Vienna from April until June. We lived in a student dormitory in the outskirts of Vienna, very close to where the Ellmanns had lived before their departure to Argentina. We took German language courses at the University, which were not regular and not intense, so there was plenty of time to visit Vienna and travel around central Europe.

Today, Vienna is an incredibly exciting, young and vibrant city, but in 1975 it made a tired and sad impression on me. It was filled with pedantic old people, for whom manners seemed to be the only thing that really mattered. Even classical music was boring, with mostly only Mozart or Haydn to be heard, and in only a few venues. After 10pm, there was literally no one on the streets. The university students we met were all trying to escape to Germany or other parts of Europe during weekends. The big change for Vienna came in 1989, when communism fell in the former East Bloc countries and Vienna became once again what it had been before WW2: a gateway from East to West, not just of people, but of ideas; a melting pot of Eastern and Western European cultures.

In order to get around central Europe, Fer and I mostly hitchhiked, often accompanied by girlfriends. Hitchhiking was much more common in 1975 than it is today, but it was nevertheless not a very efficient transport system. Especially when it rained, cars would stop less frequently, and it was not uncommon for us to have to wait for several hours before we were picked up. On one of these occasions, when night struck and there was nowhere to sleep, I swore to myself that if ever I owned a car, I would take every hitchhiker, especially if it rained or at night. I have kept my promise. Over the years, more than once I’ve not only picked up hitchhikers, but invited them to eat at our home and given them money, something that puzzled, if not embarrassed my first wife.

In May 1975, Fer and I, accompanied by two Swedish girls who we had met in Vienna, decided to visit Prague for a few days. At the time, a visa was necessary to visit Czechoslovakia. At the Czech Consulate in Vienna, we were asked whether we had hotel reservations and we said no, that we would figure it out once we were there. The employee told us that it was unwise to travel without reservations, but we paid no attention.

At the Czech-Austrian border the train stopped, and all passports were very carefully controlled. When the border policeman opened my passport, he spoke to me in Czech and then signalled that I should get out of the train. I was ushered into a small room at the station and three people started to interrogate me, initially in Czech and then, realising that I didn’t understand a word, in a mixture of German and English. I had to explain in detail where I came from, what I was doing in Austria, what I intended to do in Czechoslovakia, who I was going to visit, etc. After an hour, I was let go and the train continued to Prague. It was much later that I realised that the border crossing had happened in an area that is quite close to where the Simkos are originally from. My family name aroused the suspicion that I might be someone who had escaped Czechoslovakia and/or was returning ‘home’ to create trouble. At the time, the nation of my ancestors was under a particularly tough communist rule, following a short-lived period of liberalisation in the spring of 1968, which had been brutally ended by the invasion of Soviet forces.

When we arrived in Prague it became obvious that the man at the Czech consulate in Vienna had spoken the truth, and that it had been very unwise to arrive without a reservation. The few existing hotels were totally booked out. It was Easter and thousands of East Germans had flocked to the Czech capital. Most of them were spending their nights in their small cars.

We spent the first night sleeping on benches in the railway station, but it was gruesome, and our Swedish friends were not amused. Then I remembered that before leaving Buenos Aires, Paul had given me a little notebook into which he had inscribed the names and addresses of as many people as he knew or had heard in Europe. ‘Just in case,’ he had said.

I had never used this notebook, but now I consulted it and an ‘Aunt Bertha’ appeared as living in Prague. A few minutes later, the four of us were at her doorstep. Bertha spoke no language other than Czech, but nevertheless understood our predicament and the four of us spent the next three nights in a little room in her apartment. I still don’t know what connection she had with our family, but she was clearly thrilled to have foreigners staying with her, and gave us long explanations about all the wonderful things to do and see in Prague (unfortunately, in Czech). And we, of course, were thrilled to sleep in real beds.

Today, Prague is considered one of Europe’s most beautiful cities, full of magnificently preserved baroque buildings. It’s a city of culture and music, and the food is exquisite. In 1975, the buildings were there, but they were covered by a thick layer of soot. There were no restaurants in communist Czechoslovakia, no music and no cultural events. Whatever Aunt Bertha had in mind for us, we didn’t see it. The only thing we did see, were people in run-down bars, drinking beer at all hours of the day (including in the early morning, before going to work). There was a palpable sadness in the air. It was impossible not to see that communism did not result in a happy society.

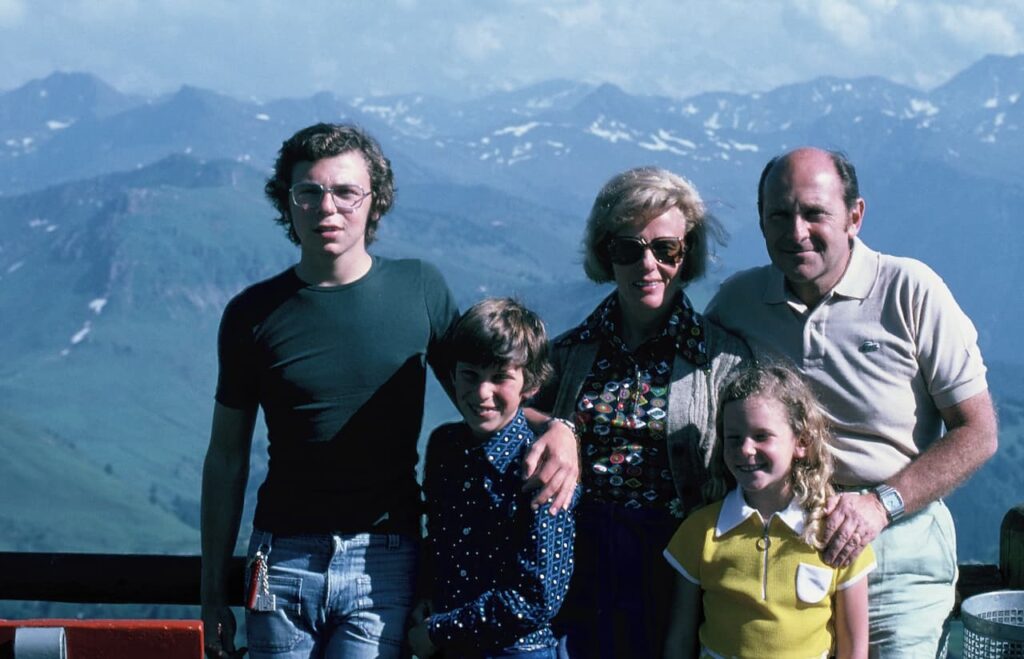

After Vienna came Lausanne, but in between Paul, Lisl, Edi and Sonia came to visit me. As on other occasions, my parents took decisions without really thinking them through or consulting with me. Paul and Lisl just forgot that this was supposed to be my ‘year off’. After several months of total freedom, I had become a happy hitchhiking backpacker. I was now forced to stay in luxury hotels and spend time on buses and ‘guided city tours’, surrounded by my 10 and 7-year-old siblings, with whom I had virtually nothing in common. I was totally frustrated and a few times during our visit to Scandinavia, Holland and Switzerland, simply escaped and spent the afternoon by myself, returning only for the evening meal. Still, my parents didn’t quite figure it out and insisted on accompanying me to Lausanne, where I would spend the following months, to ‘see where you would be staying and ensure that all is well with you’. I was ashamed and told none of the other students I met, that my family was around.

But the family visit had two important and lasting consequences. One was my resolve to leave home and lead an independent life. It became very clear to me after this visit that I wanted to tread my own path, that I didn’t want others (certainly not my parents) to impose themselves on me. I reasoned that this could only happen if, geographically, I would be as far away from home as possible. The second consequence was unexpected and transformational.

During our stay in Amsterdam, while on a walk with Paul through the canals, I told him that I had ‘great news’. After months of searching, I had obtained a job at the Amsterdam Youth Hostel. ‘Oh,’ said Paul, ‘and what will you be doing there?’ ‘I’ll be in charge of cleaning, changing bedsheets and also helping out in the kitchen,’ I said very proudly. ‘And when will this job start?’ Paul wanted to know. ‘As soon as I finish in Lausanne,’ I said.

‘Well,’ Paul began, ‘first let me congratulate you. It’s not easy for a 17-year-old to find a job these days, especially if you’re not from the same country. Now let me anticipate what’s going to happen next: you’ll be motivated and do your job very well. After a while, the Youth Hostel management will figure out that you speak a few languages. They’ll move you to the reception, where once again you’ll do very well. After that, they’ll realise that you’re good with numbers and they’ll put you in the Accounting Department. After a few years, you’ll become the director of the Youth Hostel. After that, you’ll probably work in a larger hotel. And then, one day, you’ll be like me.’

I was pleased with what I was hearing, but confused about the last sentence. What do you mean, ‘like me’? I asked. ‘Well,’ Paul said, ‘you’ll be materially well off, but uneducated.’ Next, Paul spoke to me in such a way like he never had in the past. He was totally calm, candid and very articulate. ‘Having a big home, a car and money in your bank account is good, but it’s not enough,’ he said. ‘You will have a much more fulfilled life if you are educated. Look at me,’ he said, ‘I have everything that I could have dreamt of materially, but I miss having had an education. It was not possible in my case, because of the war and the circumstances in which I grew up. But you have the option of going to school. Don’t miss it,’ he said. ‘In life, there is a time and a place for everything,’ he concluded, ‘but you need to be smart about what you do at different moments, because not every option is available to you at every stage.’

Paul didn’t say ‘You can’t work at the Youth Hostel’, he didn’t say ‘I insist on you returning to Argentina’, he understood that I wanted to be free. He rose to the occasion with a brilliant message, that struck a chord with me. I said nothing at the end of our walk, but the seed for my future had been sown.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko