The three months I spent in Lausanne turned out to be a game-changing time for me. Fer and I each had a single room at the Avenue de Rhodanie 64, a student accommodation that still exists and, then as now, also included a communal kitchen. It was surrounded by open fields and was located only a few minutes’ walk from the lake and the Université de Lausanne, where I was enrolled.

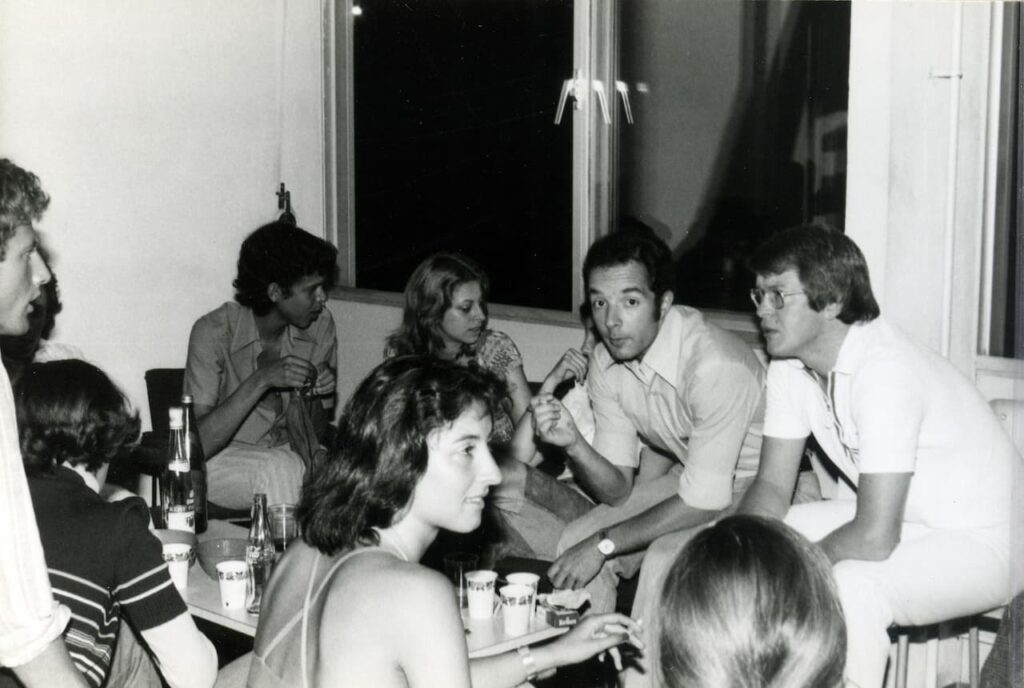

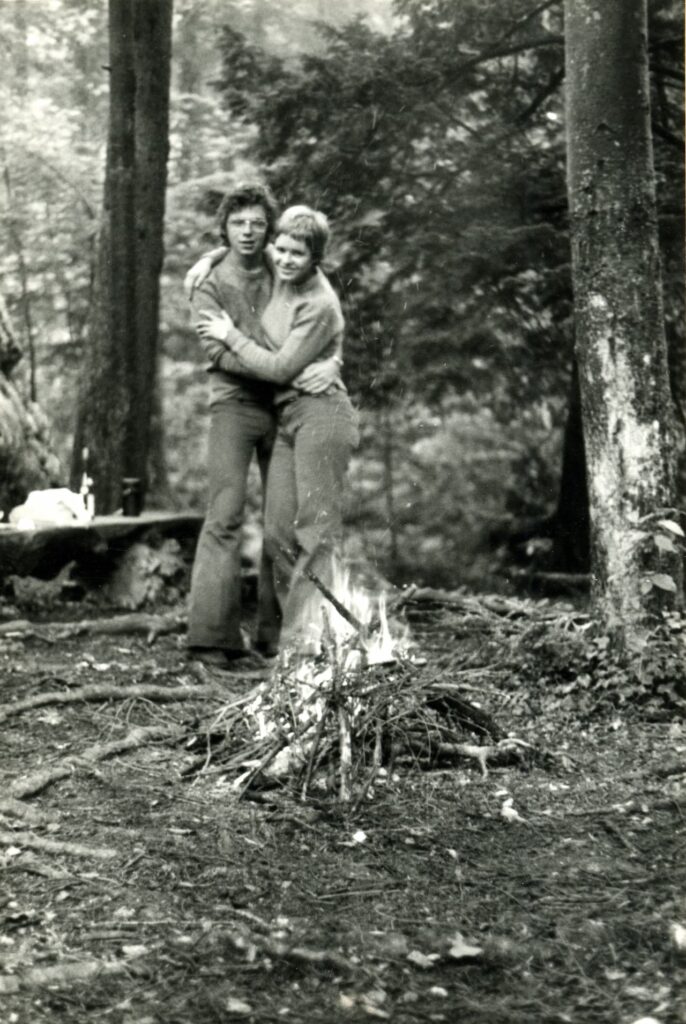

My French language courses took place only in the morning, so the rest of the day I hung out with the other students, who came from all over the world. It was during this summer that I met Kirsten, who I’ve continued seeing to this day. Here also, I met Nikki, who would play an instrumental role in my decision to study in the US. It was also in Lausanne that I had more than my fair share of romantic adventures.

The time in Lausanne also helped me see what was truly important to me—I realised that living in a place of natural beauty and close to nature, made a big difference. In Lausanne it became clear that I didn’t care much for big cities and late nights out, but that mountains acted like a magnet on me. I also loved the Swiss way of life—the quiet, the honesty of the citizens, their tolerance and democratic values, their healthy lifestyle, and the fact that it was such an international place, where you could meet people from all over the world.

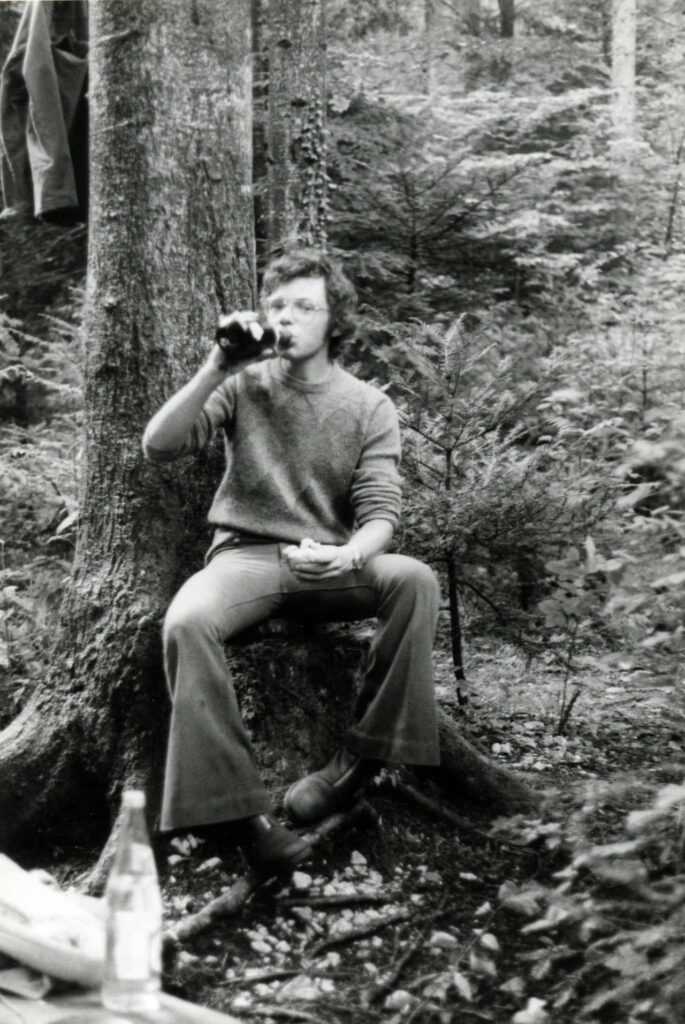

Almost every weekend I went on excursions, mostly to the Alps, accompanied by the people I had met at the university. During the week, almost every evening there was a communal meal at the Maison de Rhodanie. I loved the experience of cooking with others and living in community with so many other students. And then there were the many romantic involvements.

One afternoon, Fer and I went for a walk to the Rochers de Naye, a beautiful spot offering breathtaking views of Lac Léman. It was only when we got back to Lausanne that I realised that I had lost my keys! Not only did I have to spend the night sleeping on the floor in Fer’s room, but the cost of replacing the keys was prohibitive. And my keyholder included my Swiss army knife, which I used every day and which was also very expensive to replace.

The next morning, I called the Montreux train station. The person answering said that no keys had been dropped off the day before or that morning, but asked for further details and when I said that I had been to the Rochers de Naye, he said: ‘Ah, I received a call from the man in charge of the train station at Caux, he said that keys were found.’ I called the Gare de Caux and the man described to me what he had received—they were indeed my keys and the Swiss army knife! Overjoyed, I took the train from Lausanne to Caux. When I arrived, the man at the train station explained that someone had found my keys on the path down from Rochers de Naye—‘You must have stopped for lunch and left them there,’ he said. I asked whether he could give me the person’s name. He said he didn’t know the man personally, and that the key finder had wanted to remain anonymous. ‘OK,’ I said, ‘then please tell me what I owe you.’ ‘It’s 10 centimes,’ the man said. ‘10 centimes??’ I asked. ‘Yes,’ said the man. ‘Why 10 centimes?’ I asked. ‘It’s the price of my phone call to the Montreux train station,’ the man at the Gare de Caux said.

This incident gave me an early introduction to Switzerland, which I wouldn’t forget: the decency, the care, the humility, it all stayed with me and it was one of the reasons why, much later in life, I jumped on the opportunity to settle in this great country.

I was scheduled to return to Argentina in October. In September, Paul’s words from Amsterdam came back to me, and I decided that he was right. My next step would be to go to university—but not in Argentina—I would do everything to study abroad. This would allow me to be free from my parents’ tutelage, open up larger perspectives for me and, hopefully, experience life surrounded by a community of students from all over the world, as was the case in Lausanne.

I reasoned that Cambridge University would be the ideal place for me. I had loved the town and the stunningly beautiful university campus. So, on the spur of the moment, I boarded a train to the UK, arrived the next day, and in the early hours of the morning, knocked on the door of King’s College, a place I remembered had beautiful buildings, including an iconic XVth-century chapel.

The porter asked me what I wanted, and I told him that I wished to enrol as a student. He looked at me with slightly bemused eyes and asked me to wait in a room next door. After a short while, an elegantly dressed gentleman arrived. He introduced himself as a ‘tutor’ (I later learned that ‘tutor’ is the name of a professor at Cambridge). He asked me where I came from and what my credentials were.

‘I have a secondary school baccalaureate from the Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires,’ I said very proudly. ‘Aha,’ said the tutor, ‘and what else do you have?’ I looked puzzled, so he added: ‘How many A-levels do you have?’ ‘A-levels?’ I asked. ‘Yes, which A-levels have you taken and which marks did you get in them?’ the tutor wanted to know. ‘What’s an A-level?’ I asked. ‘A-level is short for “Advanced Level”’, said the patient tutor, ‘it’s an exam that students take when they finish secondary school in the UK. There are A-levels in dozens of subjects. You will need three of them with an A grade to apply to our college.’

‘That’s ridiculous,’ I said. ‘As I just told you, I already have an Argentinian baccalaureate—and in my school we studied many more than three subjects!’ Before the man could respond, I added: ‘In case you’re unfamiliar with the Argentinian educational system, I attended the country’s best high school!’ ‘Well, you’ll still need three A-levels if you want to apply here,’ said the tutor. ‘So what you’re saying is that in order to be admitted here, I will need to start to study again the subjects I already completed in my high school?’ ‘We need to see your A-levels; the rest is your business,’ was the response.

After a short pause, I said: ‘I think you people are just absurd. You need to think of your future as an academic institution. If you want students from other countries to attend, you’ll need to change your system. Otherwise, in the future, this will place might continue to look as beautiful, but it’ll just be filled with British students. No one in their right minds will redo the work they’ve already done in secondary school, just to please you!’ The startled tutor stood up, ushered me to the door and that was the end of my plan to become a Cambridge University student.

Thirty-five years later, when my son Pablo applied to Oxford, A-level requirements were no longer required—he just applied the way I would have, with a local baccalaureate, in his case from Geneva. Did my conversation with the tutor help? I’m not sure, but I felt an undeniable sense of pride when Pablito was admitted.

On the train back from London to Lausanne, I felt demotivated and wondered what I would do next. The train I took was divided into individual compartments for six people. In my compartment there was just one other person, a boy that looked about my age. After a while we started talking. It turned out that he was from Honduras.

I told him about my experience in Cambridge. He laughed and said: ‘Go to the US! They are a lot less complicated there. All you need is your secondary school certificate. If they like you, they’ll even pay for your studies!’ ‘How will I find out about US universities and which one to apply to?’ I asked the Honduran. ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘just visit any US embassy, they have lots of information and are eager to help foreign students.’

Full of optimism, I decided then and there: I would study in the US, a country I had never visited. I didn’t even bother stopping in Lausanne, but continued on the train to Bern and marched straight into the US Embassy. After a short wait, the cultural attaché received me and explained that my Honduran friend had been partially right—yes, US universities would accept my Argentinian credentials, but I would nevertheless have to take an exam called SAT. I said that I didn’t want to study again what I had already studied in high school, and the man said, ‘No, the SAT just measures how bright you are.’ ‘Where could I take this exam?’ I wanted to know. ‘Here at the Embassy,’ he said. ‘The next exam is in December.’ On the way out, he suggested that perhaps I should take a few practice exams and handed me a thick book with 10 tests. He gave me a second, even thicker book, which included the names and short descriptions of thousands of US universities.

Back at the Université de Lausanne, I met up with Nikki Seligman, who I knew was a freshman at Harvard College. She was taking the same summer course as me and we saw each other often.

Nikki was beautiful and very smart. She told me all about campus life in the US, explained to me that the SAT exam was ‘not a big deal’, showed me some of the papers she had written and photos of her dorm. Nikki, a good friend of Caroline Kennedy, who later also attended Harvard Law School, from where she graduated magna cum laude, would become an internationally-known lawyer, defending President Clinton during his impeachment trial in the 1990s. She was also for many years President of Sony Corporation and is now a Board Member of WPP, the world’s largest advertising conglomerate. In the summer of 1975, she was instrumental in giving me the final push and confidence to apply to US universities.

At the end of September, it suddenly dawned on me that I had better inform my parents, who were clueless about my plans and thought that I’d be returning to Argentina in a few weeks. So, I hastily wrote a letter to both of them, telling them about my intention to study in the US and informing them that I had secured a room at the Maison de Rhodanie until the end of the year so as to prepare for the SAT exam. The room was at no cost—I would help out in the kitchen in return for room and board.

After a week or so, I received an urgent message through the University of Lausanne to call my father. At the time, I had no phone contact with my family, as it was prohibitively expensive to call Argentina. But Paul, practical as ever, had carefully noted down ‘emergency contact numbers’ before I left Buenos Aires, so now he reached out to me through the university.

I was afraid of what he might tell me, but when we spoke, he was very positive. He said that the idea of studying in the US was excellent, that he endorsed it and would help me. He added that he had made enquiries and that writing applications was not so easy. He therefore suggested that I return immediately to Argentina, so that we could work on the applications together. He added that the same SAT exam could be taken in Buenos Aires too.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko