Education always had the highest priority for my family, especially for my father who felt that being materially well off was not sufficient, that education provided an essential foundation for a fulfilled life. He also thought that he had been able to succeed materially, as well as he had, in a large part because of the war. He felt that he had grown up at an exceptional time, when self-made individuals with no formal education had had opportunities which would not reoccur in the future. He therefore was hopeful that his children would attend the very best schools, in order to provide them with solid life foundations.

This started with the right choice for my elementary school. At the time, the very best bilingual English-Spanish school in Argentina was ‘St. Andrew’s’ and my father was very keen for me to be accepted there. I had attended an English language kindergarten called ‘Storyland’, so I did have a rudimentary understanding of English, but it was unclear whether it would be sufficient. At the time, St. Andrew’s took 30 boys each year, of which only 15 were enrolled from non-native English-speaking families such as ours. About 150 boys applied each year, so the competition to get in was very tough.

The most important part of the application involved a one-to-one interview with one of the teachers. My parents knew that a frequent interview question was whether I could recite a poem, so in preparation I was taught several poems and the evening before the interview was able to recite by heart no less than eight of them.

When I returned home after the interview, my anxious parents wanted to know if I had been asked about a poem. I said that the teacher had indeed asked if I could recite one, but that I had responded that I couldn’t remember any. Paul and Lisl were visibly disappointed and dropped any additional questions, certain that I would not be admitted.

But to the surprise of everyone, I was accepted, and indeed did well academically and socially at St. Andrew’s.

What had happened in the interview was that after refusing to recite a poem, I had asked the teacher whether she would like to hear a story instead. Yes, she said. So, I told her a story about a mouse and a lion. In the middle of my narrative, the teacher, who was a native English-speaker, asked: ‘What would you do if you saw a real lion?’ to which I responded: ‘Excuse me, but your English isn’t correct. You should ask me: “What would you do if you see a real lion?”’ The flabbergasted teacher didn’t quite know how to respond, said nothing and just continued the interview.

Before leaving, I felt that I had done a good job by successfully correcting the interviewer’s incorrect usage of her mother tongue. However, I was a bit upset that she hadn’t answered my question, so I asked again if she would like to know what I would do if were to see a real lion. Yes, she said, she’d like to know. I would run away, I said, and with a big smile, shook her hand and exited the room, happy that through my intervention not only had the teacher’s English been improved, but that she had also become a more polite person.

A few days after I informed the family what had happened at the interview, my grandmother Annie asked me about the story of the mouse and the lion. She had thought about it and couldn’t remember us ever discussing such a story or anyone in the family having read such a tale to me. ‘Oh no,’ I said, ‘I invented the story.’ ‘But when did you invent it?’ she wanted to know. ‘Did you think about it before the interview?’ ‘No, no,’ I said, ‘it was at the interview, when the question came up, that I invented it on the spot.’

In the 1990s, when my sons Pablo and Nico were small and we went on long walks, if I noticed that they were getting bored, I would ask them to tell me a word (any word) and I would transform it into a story. So, if they said ‘tree’, I would invent then and there a tale about a tree—for example, how the tree there in front of us had fallen in love with that other tree that we see in the distance. In love with each other, the two trees would hope that strong winds would bring them together, but it didn’t work, so they asked bees to help them. Full of empathy, two bees started going back and forth between the two trees, etc. Sometimes the stories were short, sometimes they were very long. It all depended on how much further we had to walk.

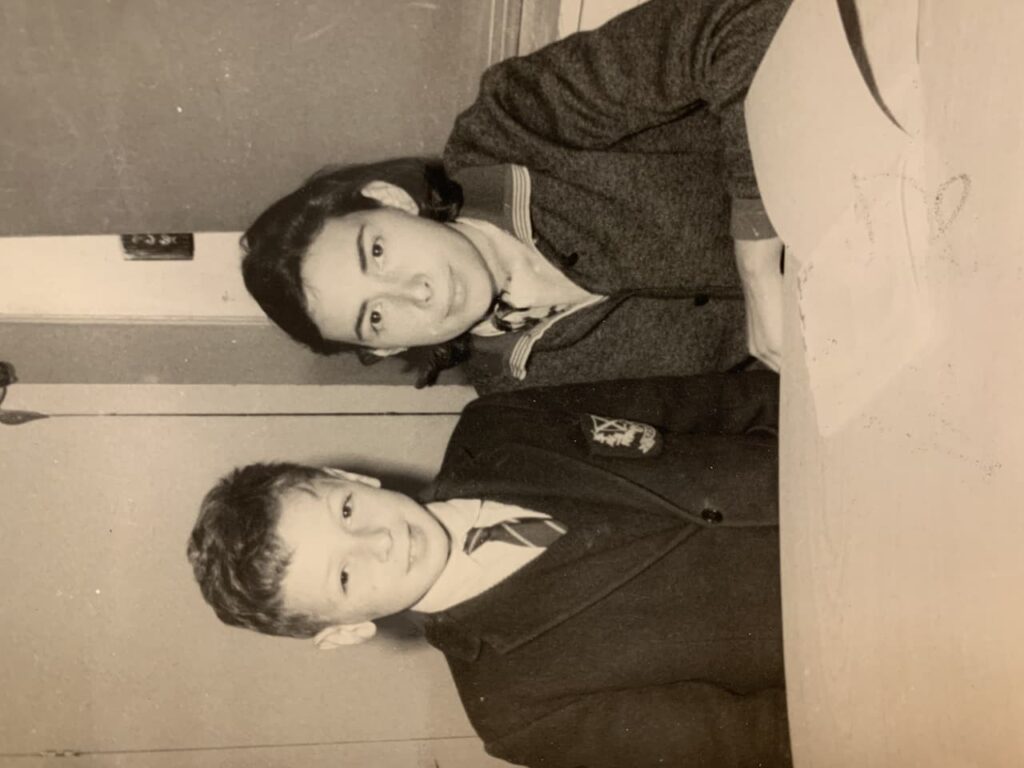

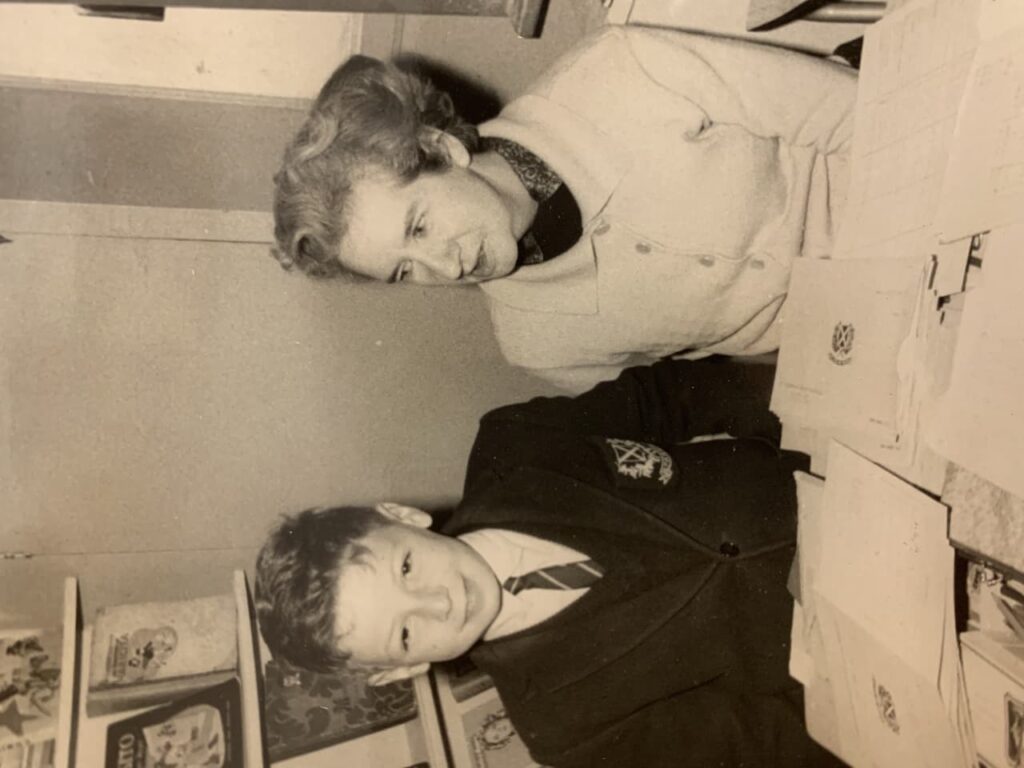

I had many friends at St. Andrew’s and was involved in plays and music. I was never much good at sports, but like nearly all kids my age who grew up in Argentina, I played football with my friends.

I had a particularly good voice (which I would lose when it mutated), a good memory and absolutely no stage fright, so I was often selected to participate in school plays. I was Jack in ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’ and the Donkey in ‘The Travelling Musicians’. I had a large group of friends and my weekends were filled with visits and/or attendance at parties.

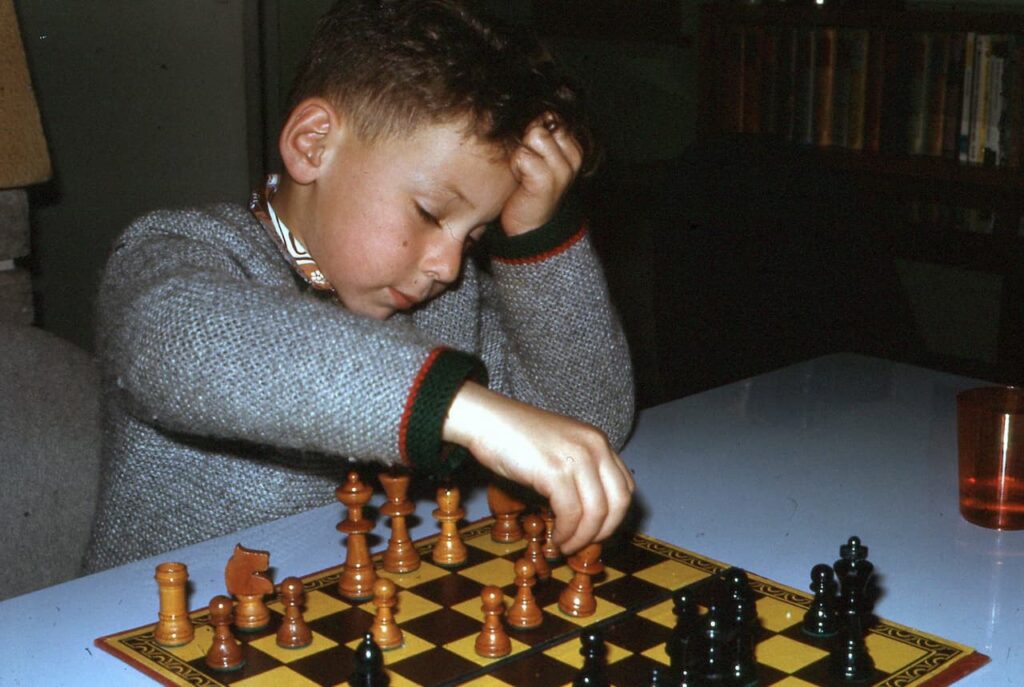

Chess was one of my favourite pastimes. I was never particularly good at it, but I enjoyed playing. It was also a good way to spend time with Paul, who spent a lot of time at the office, but was always eager to play a game or two after dinner or on weekends. With his usual enthusiasm, he bought a book about openings, which we studied for a while, but not too diligently. We both preferred to play and not to complicate our lives with long explanations. Other frequent weekend distractions included playing Memory and Monopoly, which my father thought were good activities to develop my brain and (he hoped) to foster business acumen. My mother was happy to play Memory, but the other games bored her or she lacked the concentration to stay for too long at the table.

I find it sad that many of the table games, so common in my childhood, have disappeared or have been downgraded, replaced by electronic games or solitary entertainment in front of mobile phones. The board games I played as a child brought family and friends together. It was less about winning and more about spending time together. The board games also taught patience and humility and, depending on the game, teamwork. Without the relentless beeping of mobile messages, time was slower in those days and it was in many ways a more relaxing environment.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko