Summers were often spent on the beach, often with friends, initially on the Argentinian coast, in Villa Gesell or Mar del Plata, but increasingly, as my parents’ income rose, in Punta del Este, Uruguay. Punta del Este was at the time a small village nestled among endless beaches. There were practically no high-rise buildings. During the summer season, from late December to early March, Punta (as we called it) was filled with Argentinian tourists. Eventually Paul bought an apartment on the 13th floor of the Edificio Opus Alpha, the only tall building, with breathtaking views.

In the time of no mobile phones (and few landlines), people gathered spontaneously on the beach, usually never arriving before 1pm (mornings didn’t exist, people went out until very late and slept in). In Europe, vacationers typically look for out-of-the way, secluded spots, but in Uruguay, where beaches stretch for hundreds of kilometres, the attraction was to be in the same place as everyone else. So, people would arrange to meet at this or that ‘parador’ (a restaurant on the beach) and spend the afternoon together. If you looked for someone in particular, and they weren’t at the parador you thought they would be at, there was no way to know where to find them—the beaches were just too long. Eventually, you’d bump into whoever you were looking for in the town of Punta. But this could take a few days or even weeks. Or you could leave a handwritten note for your friends in their home (if you knew where they lived—street addresses were approximative and there was no postal service).

The sense of urgency was not what it is today; timings were imprecise (few people would take a watch to the beach) and the atmosphere was one of ‘go with the flow’. You also hardly knew what was happening in the world during the summer in Punta. Sometimes a newspaper salesman would show up at the beach, but not always. Often the newspapers he carried were old, or he only had local papers, which included very little international news.

You never knew how many people would show up for dinner, or at what time dinner would take place, because it was so difficult to communicate. So, things just happened. A friend might suggest that you go to his home to have hot chocolate and biscuits, and then things would drag on and you just spent the night there. His parents might try to reach yours to tell them what was happening, but it didn’t always work, so you would reconnect with your family the next day. Or the reverse would happen, and friends would stay at your home, sometimes for a few days.

Because there was so little to do (Punta had only one cinema, which was usually full), and board games were difficult to carry to the beach, the main entertainment was people. We just hung out and spent time with each other. We talked and talked and talked. We did play the occasional game of cards (usually ‘Truco’, a game that could be played alone or in pairs), and I can remember more than one afternoon spent playing a dozen games or more.

But the main part of our day consisted in just being with each other. Sometimes we would walk over to where the fishermen stood and watch them. They rarely caught anything, but when they did, it was really big news and crowds gathered on the beach to accompany them while they hauled in a corvina, a very tasty local fish. Very occasionally, Paul would rent a boat and we would go fishing, usually without much success. But once, I must have been ten at the time, I caught a corvina. It was a day I’ll never forget.

When the waves were good, my friends and I would ride them non-stop. There were no boards on the beach at that time, it was all about body surfing. One afternoon, when I was eight, my friends and I rode 100 waves before collapsing on the beach.

The summers in Punta are unforgettable to me. The long afternoons, the sand, the waves, the wind, the many long conversations, they have left an imprint in me that has not eroded with time. Wherever we travel, if there is a long and deserted beach, the memory of Punta returns to me instantly. I’m thankful to my parents to have offered me so many Punta summers.

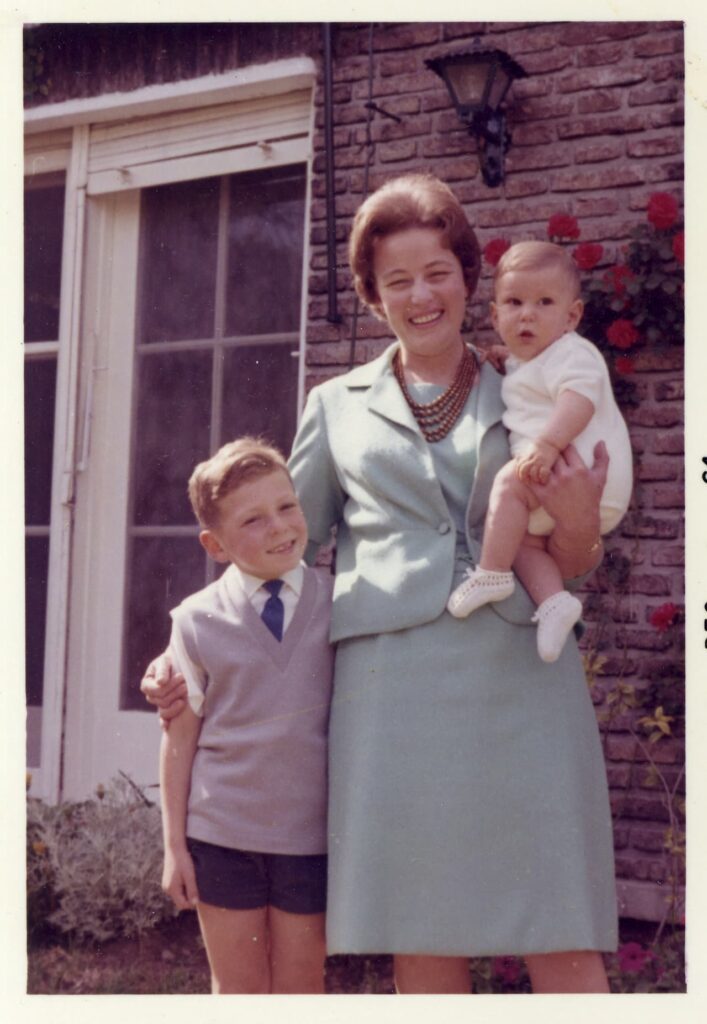

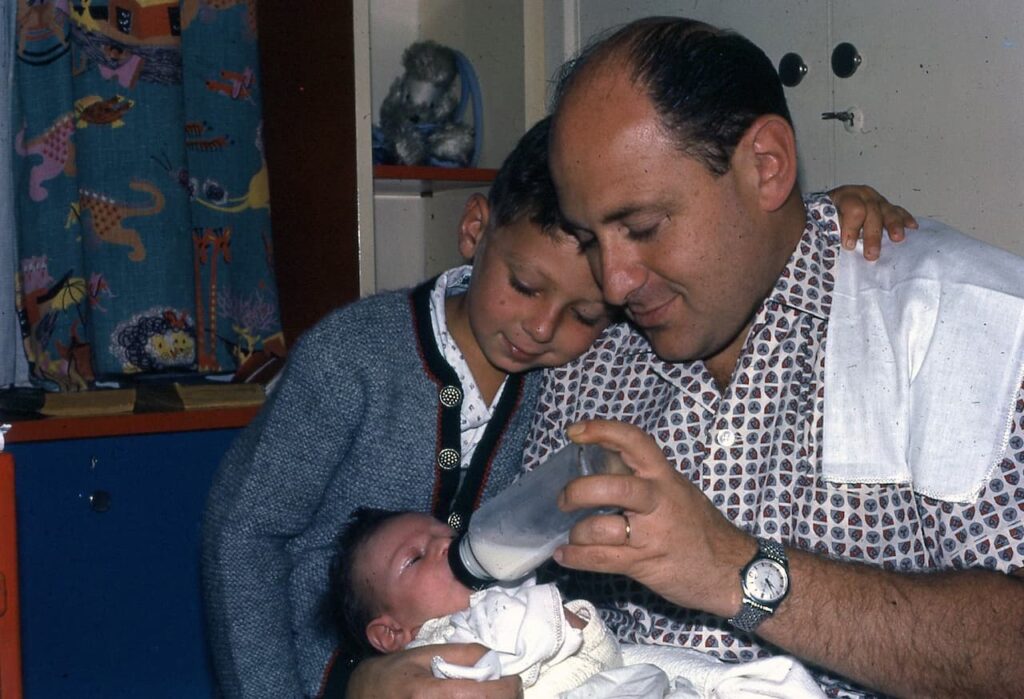

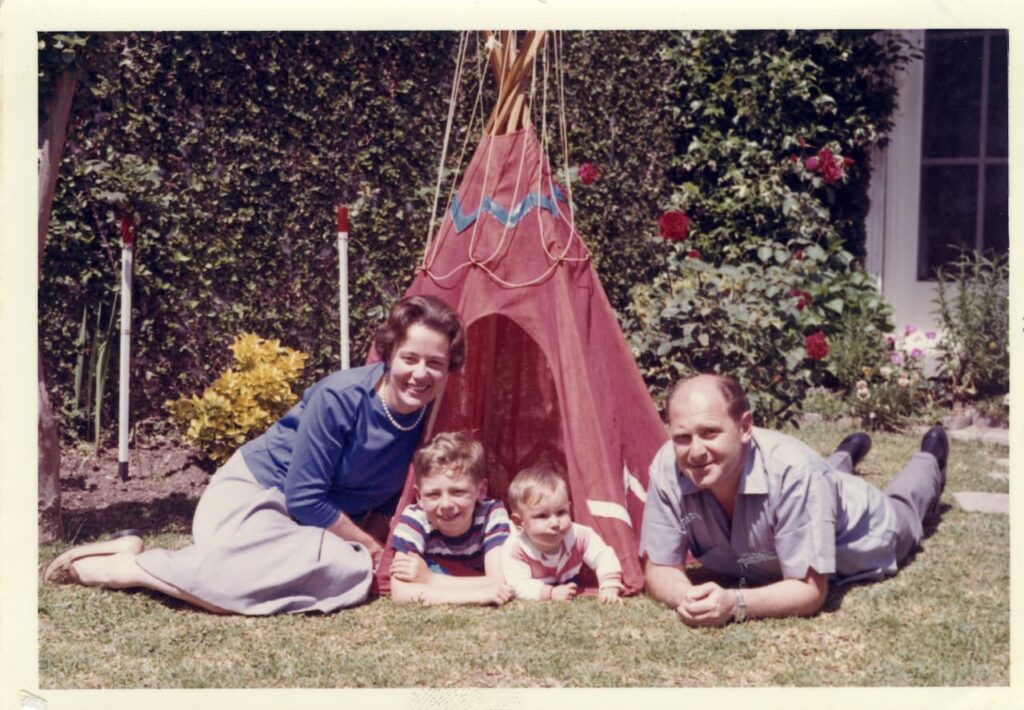

In February 1964, my brother Eduardo was born. My parents were greatly relieved, since my mother had had a string of miscarriages since my birth in 1957 and Paul and Lisl were worried that I might become an only child. As in other situations in my life, my parents decided what they thought was best for me, based on what ‘society’ or ‘common sense’ would dictate, but without really thinking it through or focusing on me as an individual.

I was, in fact, was quite happy as an only child and certainly showed no signs of ‘needing a sibling’. I reacted in a neutral way when Edi (as we’ve called my brother) arrived. I was neither upset nor elated; it was just another event in my life. I did, however, give a clear sign of how I saw the relationship with my brother a few days after he was born: my parents had organised for me to spend five days with Peter and Vicky Lux in Tigre. As we were leaving, I said to my mother: ‘Upon reflection, I think I’ll spend not five, but fifteen days at the Lux’s, so that when I come back, Edi might be old enough so that I can do something with him!’ (‘Wenn ich dann zurück komm kann man vielleicht schon etwas mit dem Baby anfangen!)’.

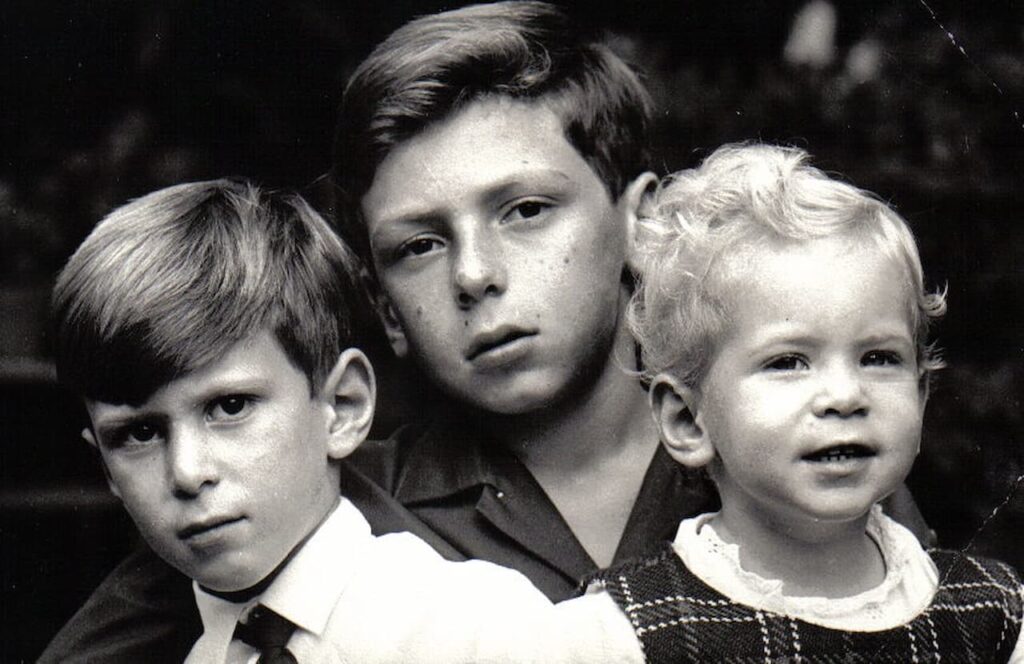

For a long time, my relationship with Edi was not a very strong one, the difference in age was too large to warrant this. It was many years later, after I had left Argentina, that my connection with Edi would steadily grow. Today, I consider him not just a brilliant brother, but also a great friend. He is one of the smartest, wittiest and best people I have ever met, the one person in my life, other than you and my sister Sonia, that I would say anything and everything to. I admire the way he has constructed his life, the devotion to his family. I admire his ethics and the disinterested, passionate way in which he has bonded to me and to the rest of our family. I am deeply thankful for the exemplary way in which he took care of Lisl in her later days, and how well he and his wife Pato took care of my children when, as adolescents, they spent extended periods of time in Argentina. He’s been an amazing brother and an incredible human being. But that happened much later in my life. In 1964, I did not necessarily need a brother, I was doing very well on my own.

My sister Sonia was born in 1967, when I was almost 10. It was a sensation for the Simkos: a girl born into a family that had produced almost exclusively males. Sonia was a very fair-skinned, beautiful little girl, with blue eyes, who bonded extensively with Edi, but a lot less with me—our ages were much too far apart for that to happen. Nevertheless, we did spend time together before I left Argentina. Our relationship would significantly and deeply grow over time and today I consider Sonia to be one of my key confidantes. She has the extraordinary ability, uncommon in humans, to listen with an open heart, and to reflect deeply before she says anything. And what she says, is usually very smart. I admire her equanimity in the face of the ups and downs of life, her devotion to her family and the immense wisdom she has collected as a psychologist.

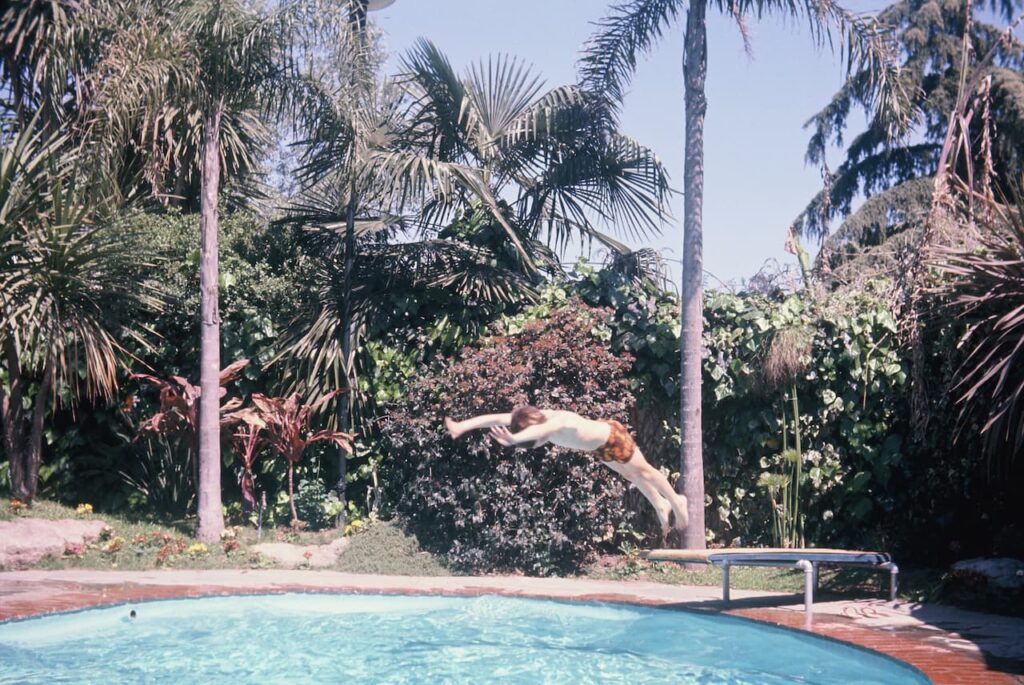

To accommodate the five of us (and to fulfil my parents’ dream of having a large garden with a ‘proper’ swimming pool), in the spring of 1967 we moved from Beccar to Terrero 2529 in San Isidro. At the time, our new home was truly on the periphery of Buenos Aires. We were surrounded by wide open fields, many of them with cows grazing. Until her death, 46 years later, Lisl would live at this address. Edi’s home is only a few blocks away from this house and today this area of San Isidro is one of the most prized addresses in Buenos Aires. Especially the garden (my parents always said that they had purchased a garden with a house) would become the place where many parties were held, and where my friends would show up regularly in large groups, dozens of them sometimes sleeping overnight under the trees.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko