To celebrate the arrival of Sonia, Szigo’s sister Margit came to visit us in Buenos Aires. She had escaped Vienna in the late 1930s. Initially she fled to London, but eventually she settled in the US just after the war. She had no children, but a whole series of husbands. She overcame her not-so-exciting looks with a lot of charm and even more business savvy. In Vienna already, she had made a good living selling curtains and drapery. In the US, her business success was good enough to attract not one, but several good-looking Americans, who saw in the lively and entrepreneurial Margit a great opportunity to lead a carefree life without having to work much.

Margit spent only a few days in Buenos Aires, but her impact on me was lasting because she offered me a shortwave radio. This radio, which I kept for many years, allowed me to listen to programs from all over the world. I would regularly tune into Radio Cuba, Radio Moscú or Radio Peking, all broadcast in Spanish. I was particularly fascinated by the Chinese, who would describe in great detail the achievements of the Cultural Revolution. And I loved to hear the revolutionary songs of the Cubans.

Richi Simko, Margit and my grandfather Sizgo’s younger brother, together with his wife Regi also fled Vienna after the Nazis took over. They spent the war years in hiding in France, erring from one place to the next, mostly in the ‘zone libre’, in the south of France. Richi got tuberculosis and it was very difficult for them, but they survived the war. Immediately after, Margit (who was already in the US) obtained a visa for them and they spent the rest of their years in New York, where Paul met them often during his travels. Regi and Richi had a son, Peter Schimko, who died quite early and who I met only fleetingly.

Religion was never a major issue in our family, but Lisl insisted that I should be exposed to the Bible. She (or Annie) would read stories from the Old or the New Testament to me in the evening before I went to bed. I also had to pray before falling asleep. I remember attending one of two religious services at the German-speaking Lutheran Church, and a meeting with Pastor Schön, but that was about it. Paul had a more distant relationship with religion. He would often say that ‘Marx and I have only one point in common: we both believe that religion is the opium of the people’. He was disinterested, if not cynical, towards anything spiritual. Lisl was more nuanced, but she was definitely not religious, and so I grew up in a home that offered few, if any, religious or spiritual impulses.

But music, especially classical, played a big role in our home. My parents had a hierarchical understanding of music, with the classical music composers being considered ‘superior’, especially Beethoven (for Paul) and Mozart (for Lisl), composers that I was encouraged to listen to, even as a small child. There was always music in the background in our home and my mother considered it culturally savvy to not only listen, but also to play music. A piano stood in our living room and my parents tried, unsuccessfully, to teach me how to play. I had neither the patience nor the talent and I quickly gave up. I was then encouraged to play the flute. This experience was also short-lived. It was only in my adolescent years when I seriously picked up playing an instrument—to the horror of my parents, it was an electrical guitar.

As part of my ‘cultural education’, my parents often dragged me to classical music concerts. In 1970, to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth, the Teatro Colón produced all nine of his symphonies. Paul was very excited and obtained excellent tickets. I slept through most of the concerts, famously even while the chorus sang Schiller’s ‘Ode to Joy’ at the end of the 9th Symphony.

Despite these less than auspicious initial steps, my parents did succeed in planting the seed of classical music in me. Over time, my curiosity and increasing love for classical music would grow and, as you know, today hardly a day goes by without me listening to a classical composer. I also retained an appreciation for opera, especially Mozart’s ‘The Magic Flute’, of which I know every line and have seen dozens of performances. But it’s only very recently that I’ve ventured into Wagner’s vast repertoire of operas. There is still that invisible barrier, a little voice in the back of my mind (it’s my father’s) warning me that Wagner’s operas are far too long, far too Germanic and that Wagner himself should be handled with caution because was an anti-Semite.

Not just classical music, but museums were a staple for my family, something that ‘no well-educated child should miss’. So, whenever we visited Europe, my mother would make sure that we literally ran from one museum to the next. It wasn’t about gaining in-depth knowledge; it was very much about ticking boxes. At the time, museums were not as interesting, there were no audio-guides and few explanations, the atmosphere was often gloomy and far fewer people visited museums than is the case today. Museums appeared sinister to me as a child, but still, as with classical music, the seed was sown and, as you well know, it’s difficult for me to visit a city (of any size) without spending time in a museum.

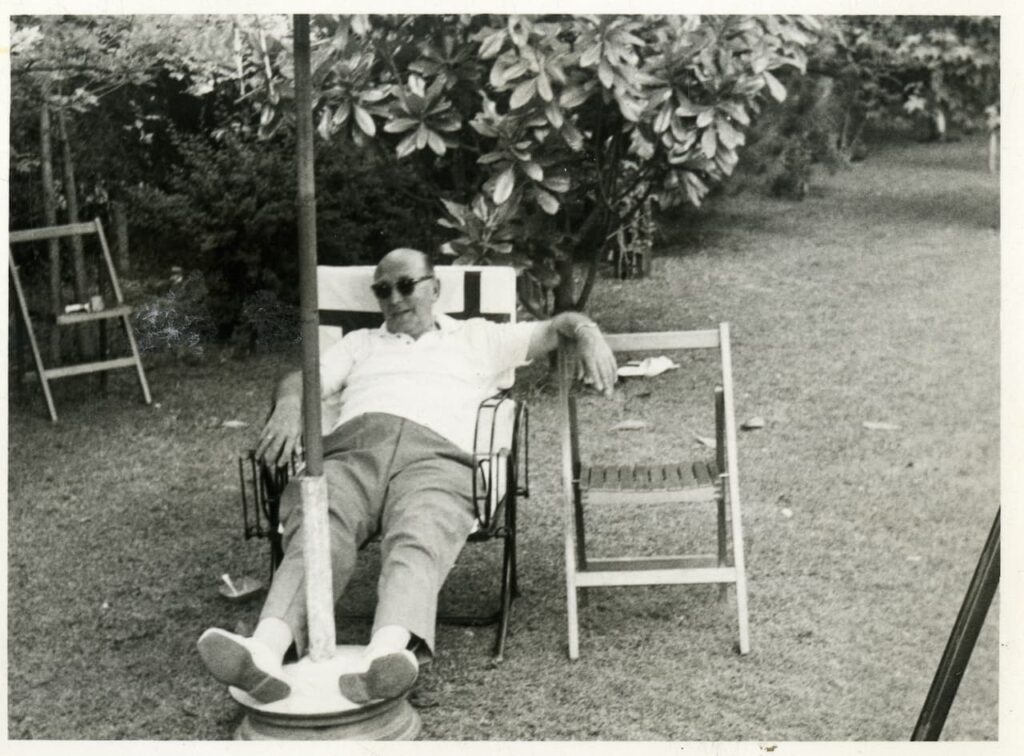

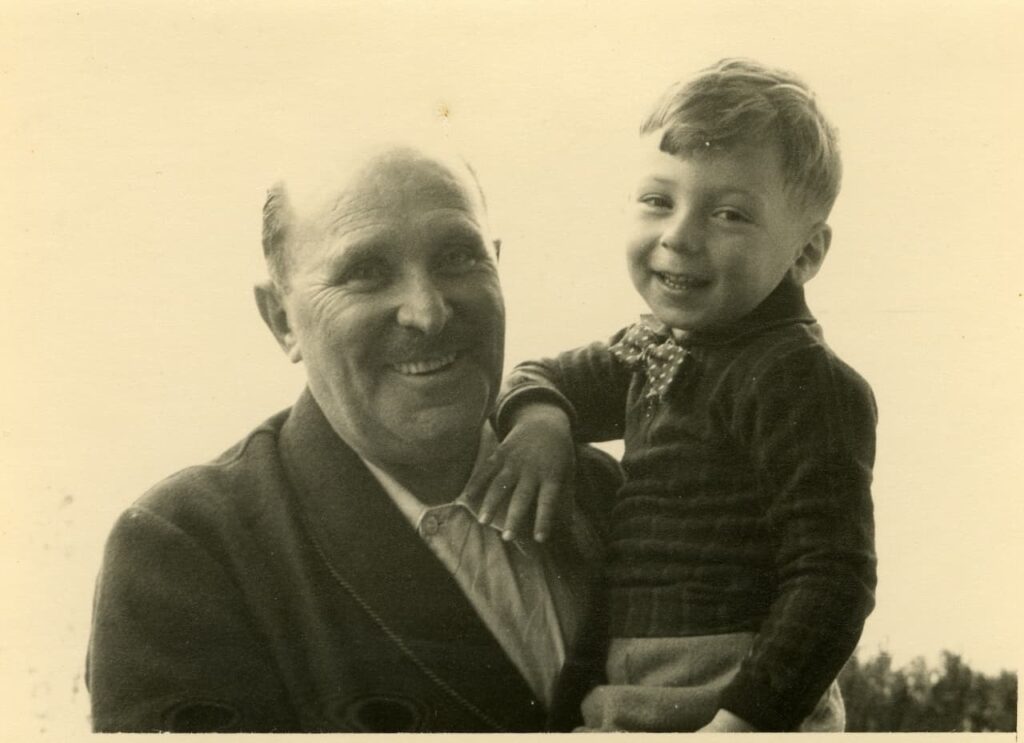

To compensate for Paul and Lisl’s efforts to inoculate me with a ‘proper’ cultural education, my grandfather Szigo regularly took me to see football matches. He was passionate about football all his life. In Vienna, he and his brother Richi supported FC Austria. In Buenos Aires, he became a fan of River Plate. In the early 1960s, he purchased two season tickets in the ‘platea’, the best area in the Estadio Monumental, Argentina’s largest stadium, where in 1978 the World Cup final would take place. At the time, large parts of Argentina’s stadiums did not have seats and huge numbers of fans would be squashed into wide open areas, where supporters would jump in unison, sing and produce music at very high decibels.

I often accompanied Szigo on Sundays to the Estadio Monumental. The key match of the day took place at about 4pm, but my grandfather would insist that we leave his home at about 10am. He said that this way we would avoid large crowds, but I think he was just looking for a good excuse to leave the oppressive presence of Lilly, and spend the day with me.

I loved these Sundays with my grandfather. He would hold my hand; we would walk from his home to the stadium (about 20 min) and spend the day in the imposing stadium, watching one match after the other (first the 12-year-olds played, then the 15-year-olds, and so on, until the main team arrived on the field, by which time the stadium was completely full of about 70,000 fans). We would eat one hot dog after another, accompanied by Coca Colas. By the time we returned home, we were both exhausted by the noise and excitement of the matches, and I had learned how easily large groups could become fanaticised.

My grandfather was a kind-hearted, wonderfully simple man, who enjoyed the little things in life, of which football was the absolute highlight of his week. He knew all the players and all the playing tactics. He would not get emotional about the outcome of a match—it was the experience of being part of something bigger that he enjoyed so much. And of course, on the Sundays when we were together, it was the time with me that he cherished so much. He would introduce me to all the people he knew, proud to be in the stadium with his grandson. He was not a loquacious or expressive man, but I could tell how happy he was every time we went to the Estadio Monumental together.

In June 1968, River played its main rival Boca Juniors, a match that always created a furore. The match itself was mediocre and ended 0 to 0, but when it finished, one of the doors of the stadium remained locked. About 70 people died that day, crushed by those who, not realising that the door was closed, kept pushing forward to get out. The tragedy created instant headlines worldwide and Paul, who was in Israel at the time, heard the news and phoned his parents immediately, thinking that perhaps Szigo and I had been to the match. My grandmother responded that yes, we were at the stadium, but had not returned home yet. You can imagine the scene when we finally showed up at my grandmother’s, about an hour and a half after the match had ended. I had invited my friend Alan Roberts that day, and we had taken our time, my grandfather commenting the match with countless others, while Alan and I consumed panchos (the Argentinian version of a hot dog), followed by choripáns, Fantas and Coca Colas. We finally left the stadium at a particularly leisurely pace, my grandfather insisting that we were better off letting the large crowds drift away before we moved…and of course totally unaware of what had happened in another part of the stadium.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko