From the time we moved to Beccar and in the following years, my father’s business grew steadily and his earnings increased significantly. The 1960s were a time of great economic growth throughout the world, including Argentina. You can sense Paul’s satisfaction and self-confidence in this photo, taken in 1962, at the Teatro Colón, in front of his newly acquired Ford Falcon, a prestigious car at the time.

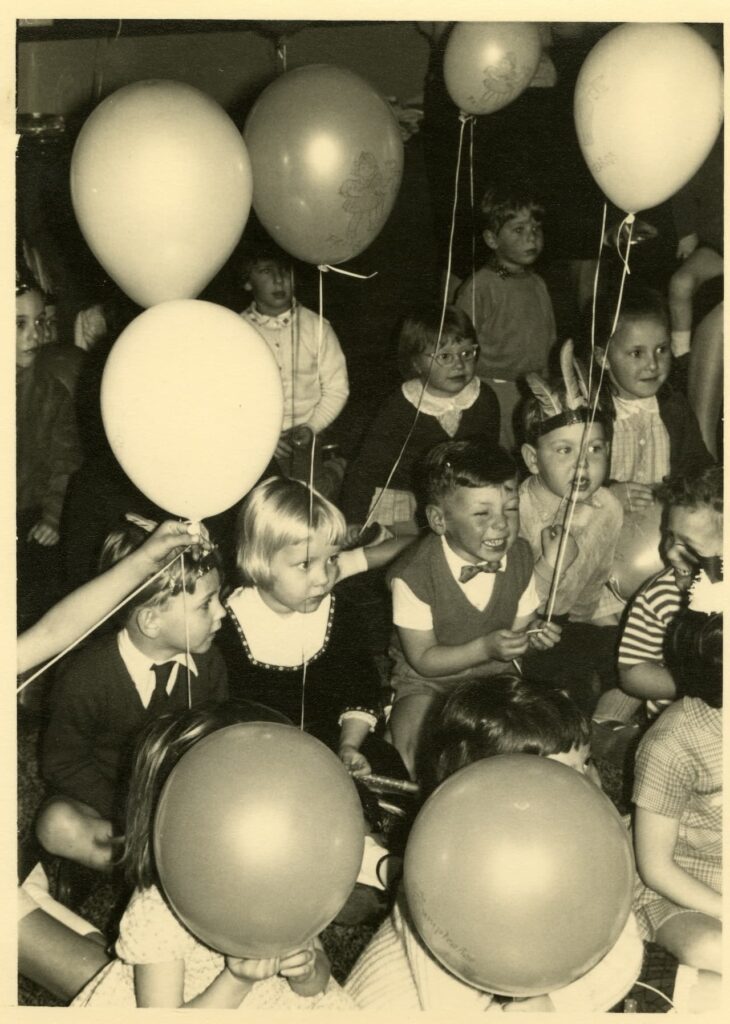

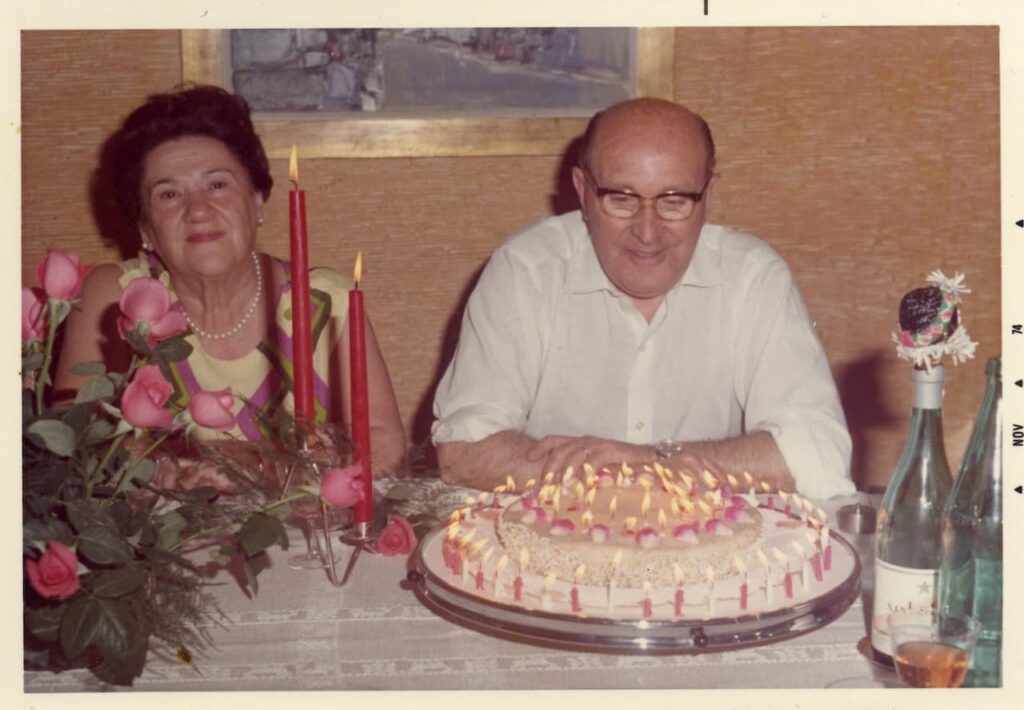

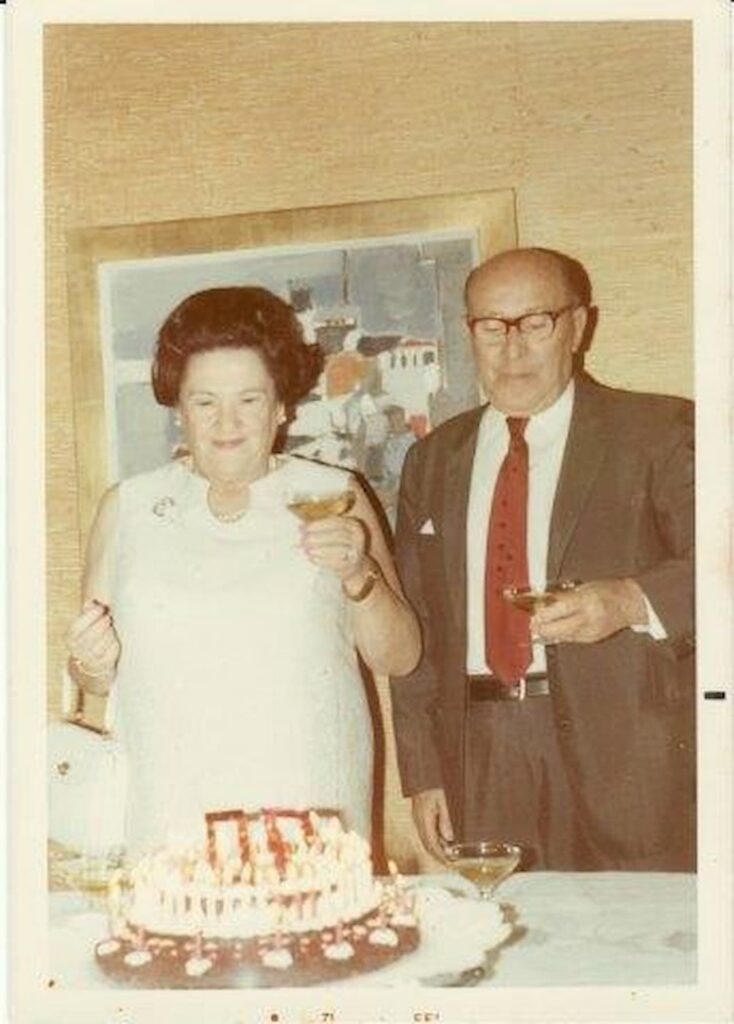

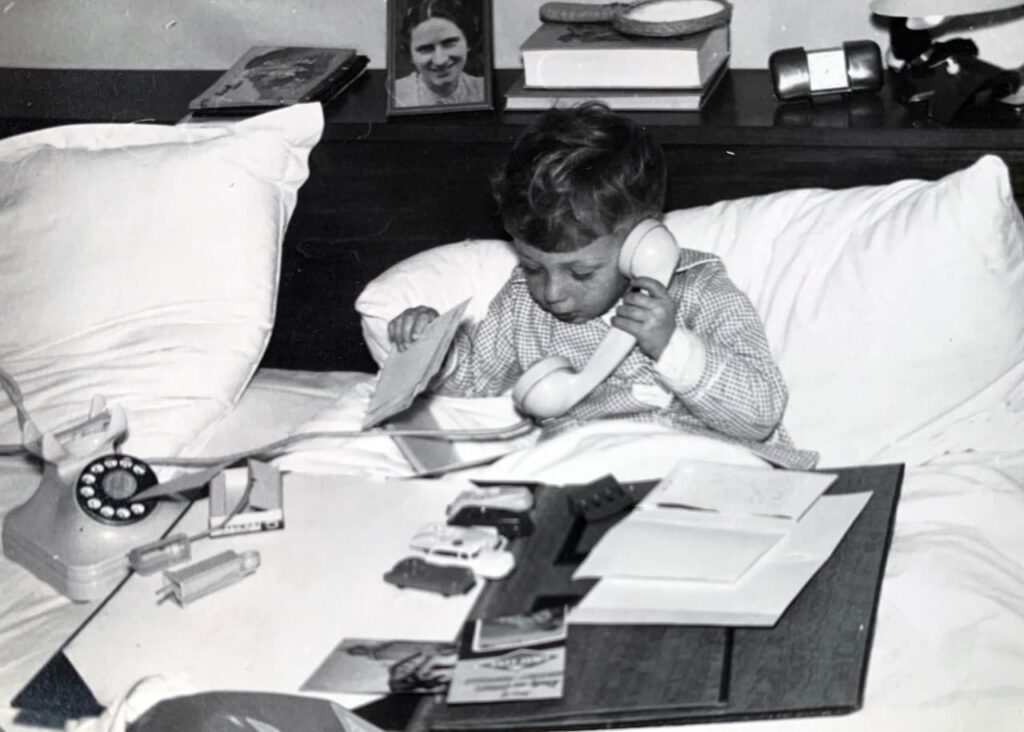

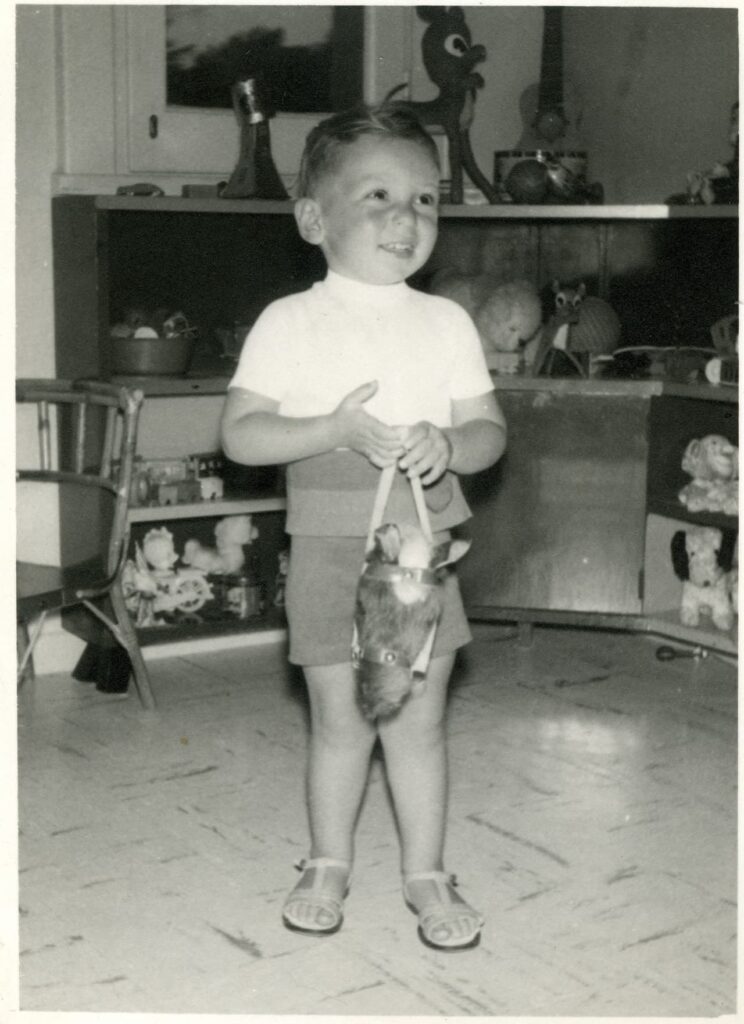

Celebrations in my childhood invariably involved home-cooked food. Birthdays were always special occasions, with elaborate cakes taking centre stage. My parents spared no details (or costs) for birthday celebrations, they invited many children and often magicians or musicians to animate the party.

Beyond birthday parties and other events like Christmas, food always took centre stage in our home and every meal (especially dinner) was a cause for celebration. We ate well and a lot, usually the heavy Viennese specialties, conceived for the cold months in Europe, but served year-round, even in Buenos Aires’s hottest months. Lisl inherited her mother’s gift for cooking and we had guests often, who would be lavished upon and could barely move after a meal at our home! Much later, my brother Eduardo convinced my mother to write down the many recipes she knew by heart, and now we both have copies of hundreds of my mother’s best dishes, many of which we still reproduce today. My love for cooking and for smartly dressed tables (but not necessarily for cakes or heavy meals), comes from this time.

My parents rarely went out (why should we, my Dad would say, we eat so well here!). This ‘hominess’ would be something that my brother, my sister and I would inherit. We’ve always felt best eating our own food, within our four walls. And, generally, spending time at home is something that, then and now, we’ve always cherished.

On many Saturday evenings, my parents would have friends over for dinner. Almost all of their guests were German-speaking, immigrants like them. After dinner, my father would entertain the crowd with jokes. He had an elephant’s memory for funny occurrences, which would invariably begin with: ‘This reminds me of a story…’ Many of his jokes involved Jews. I learned early on that Jews have a strong sense of self-mockery. But beware of a non-Jew telling a story about Jews, that’s not funny, it’s anti-Semitism!

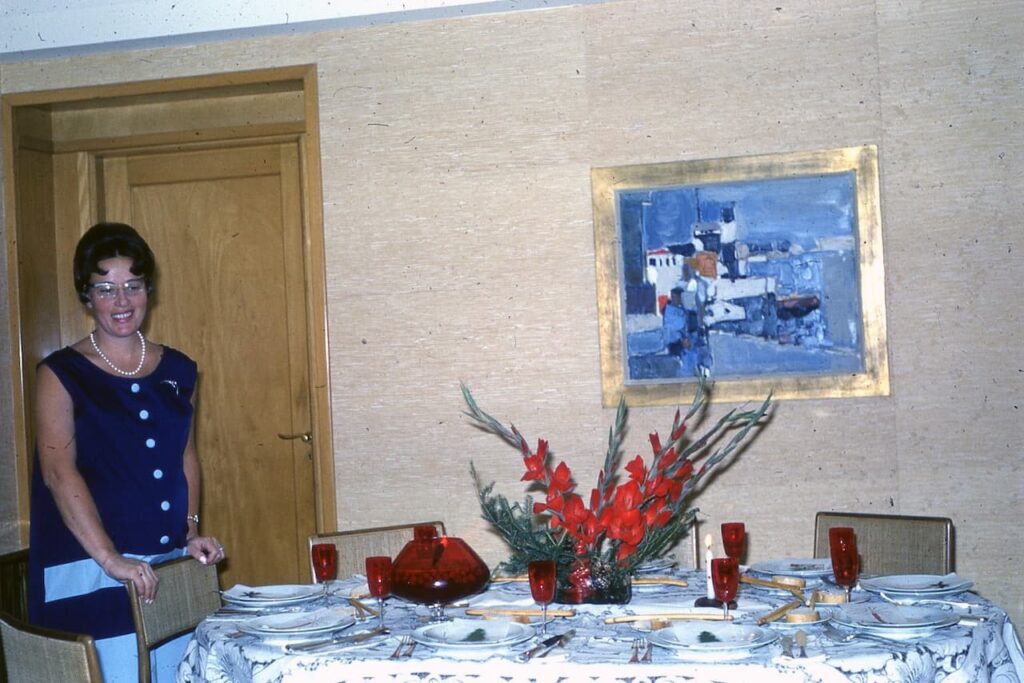

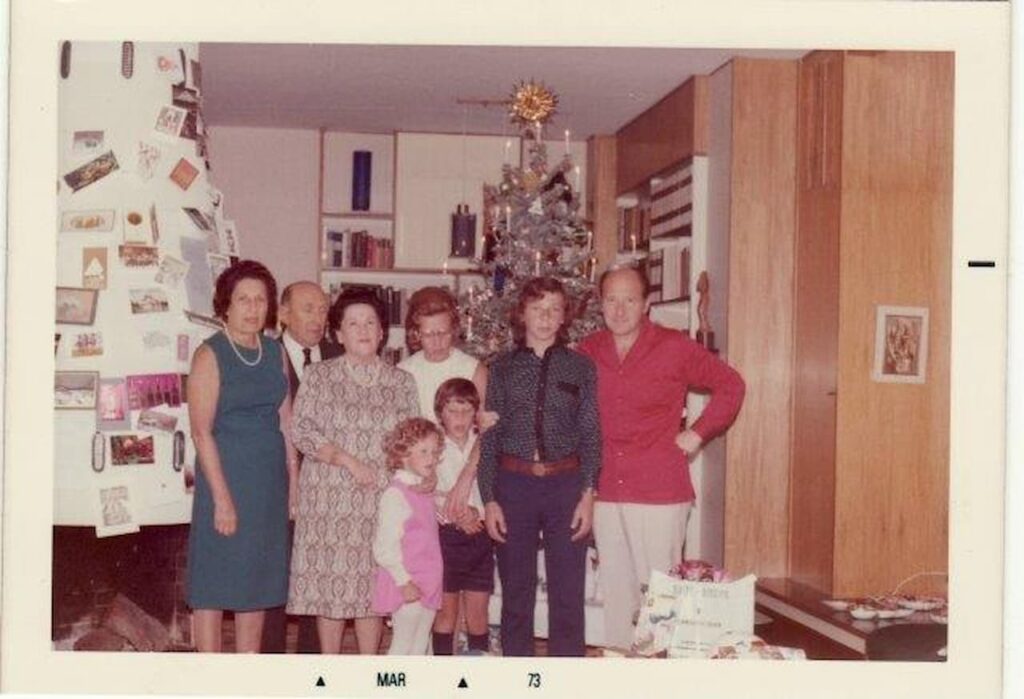

Christmas was always a very special event at our home. The preparations would take weeks and my parents closed off the living room area before December 24th, so that the children could not see what was happening. Lisl always bought a live tree (a rarity in Argentina), which was elaborately decorated with a huge number of objects (some from her childhood in Vienna), which were stored in special boxes. At 5pm on the 24th, a little bell would ring, the doors would open, and we were overwhelmed by the magic of the lit tree, the Christmas music and the many presents, all beautifully wrapped. The tree included real candles, something that no other home had, and between December 24th and the New Year, we would light the tree every evening and sing Christmas songs in German before dinner. On the 24th, everyone was very well dressed and alcohol was served (a rarity in our home). Lisl prepared a Christmas ‘Erdbeerbowle’, which she served out of a red punch bowl, into special red glasses, which she used only for Christmas. It included strawberries that she had macerated for a few days in an orange liqueur. My grandmother Lilly forbade Szigo to drink alcohol, even at Christmas, but Szigo would still get a bit tipsy by eating the macerated fruit.

For many years, dinner on the 24th started at 6pm (an absurdly early time in Argentina) and included a whole array of invariably hot and heavy dishes (a ridiculous menu, in the middle of the summer). It’s only when I was an adolescent that Lisl finally accepted the idea to drop the Austrian way of doing things—the meal now started at about 9pm and included a more reasonable selection of (mostly) cold dishes.

In the years after World War II, German-speaking Jews and non-Jews lived side by side in Argentina without any big fuss. One of the people who my father was in regular contact with was Adolf Eichmann, one of Nazi Germany’s key organizers of the Holocaust. Eichmann had been living in Argentina since 1950 under the name of Ricardo Klement and was working at Mercedes Benz when my father got to know him. At the time, my father sold rubber and other industrial goods to Mercedes Benz, and Herr Klement happened to have been one of the buyers who Paul was in contact with. After his capture and later trial in Israel, an event that my parents followed step by step, I asked my father if it had ever occurred to him that Herr Klement could have been a Nazi. Well, my father said, we of course always spoke in German when we saw each other and I knew through his accent that he was a German, not an Austrian. I also knew that with a name like Klement, he was not a Jew. But it wouldn’t have occurred to me at the time to enquire further about possible Nazi sympathies. You know, in the years after the war, those of us who had managed to make it to Argentina, were just happy to have survived. We didn’t see each other socially with non-Jews, but we didn’t want to know more than we had to about other German-speaking people’s backgrounds.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko