Both Szigo and his father participated in WW1. They were immensely proud of it. During their Sunday family get-togethers, the conversation often circled around their heroic activities as Frontsoldaten (soldiers on the front). Szigo, who was not quite 18 when the war ended, joined the army as a volunteer as soon as the army would take him (probably during the last months of the war, when Austria-Hungary began to run out of 18+ year-old soldiers). At the time, the worst offence was not to have served in the army. It was particularly important for Jewish men who had recently immigrated to show to the Austrian community that they were true patriots. Many years later, after the Nazis had occupied Vienna and the situation became increasingly unbearable for Jews, Szigo continued to believe that his participation in the army during WW1 would save him and his family from disaster. ‘The Nazis will need experienced soldiers like me, once another war starts’, he used to tell my father in the early months of 1939.

After his time as an Eintänzer and smuggler, Szigo became a wholesale salesman for Kolman & Ferber, whose business was corsets, bodices and similar products for tailors. It’s not clear how successful he was as a salesman, but his good looks and charm did get him into trouble—he had to leave his position after one of the owners wanted him to marry his daughter, and Szigo refused.

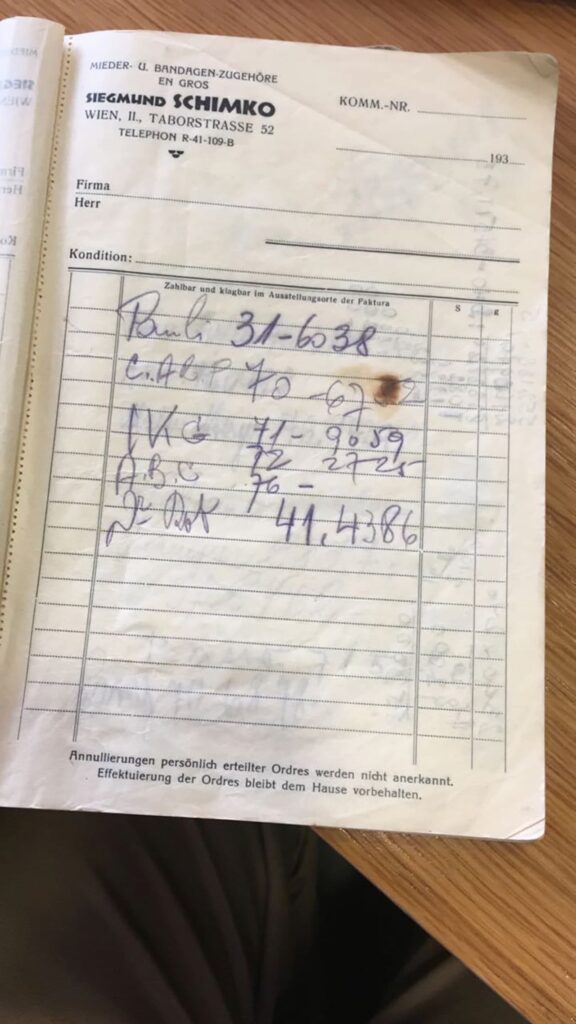

He then joined Auer & Co, a competitor to Kolman & Ferber. A few years later, around 1935, he set up a similar line of business under his own name, in his apartment. We don’t know how successful he was, but clearly he scraped enough of a living from it to maintain his family, including Käthe Karolyi, who lived with them.

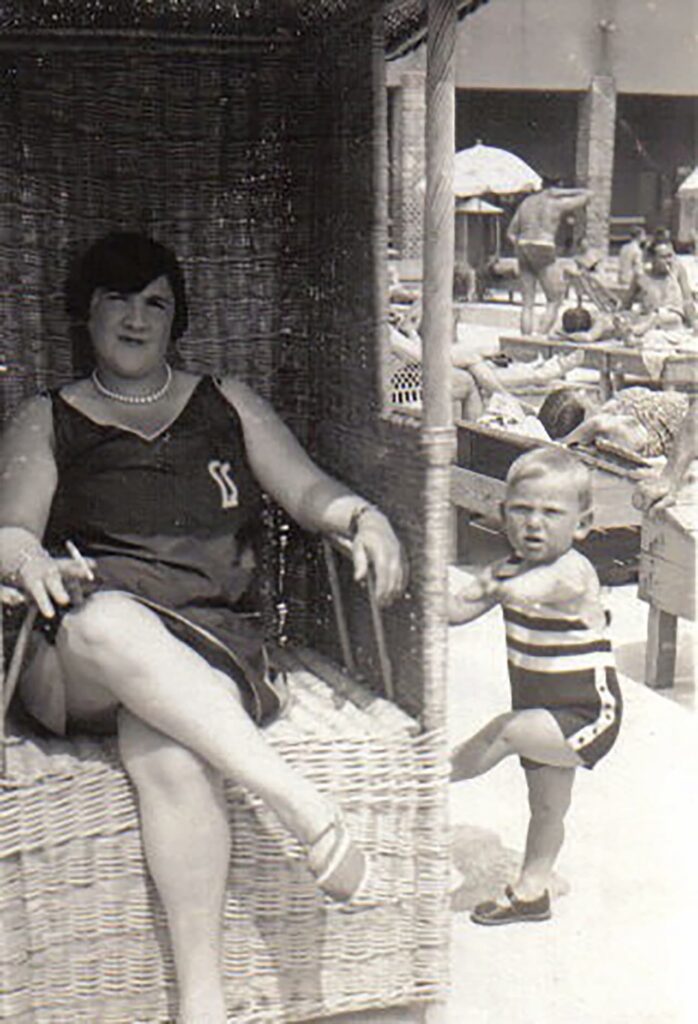

For a long time, my father Paul, born in 1927, was the only child on both sides of his family. A lively, healthy, intelligent and outgoing boy, he grew up spoiled and admired by his parents and relatives.

My grandmother Lilly was by no means an intellectual (I never saw a book in her home). She was a fussy and self-conscious lady, for whom manners were paramount and the world revolved around the constant worry of what people might think of her and her family. Leaving the home required lengthy and elaborate preparations to ensure one was ‘presentable’. She insisted on my father wearing white gloves whenever he left the home (just imagine what the gloves looked like after he played in the sand). The boy was required to wear shorts until his 18th birthday and force-fed to ensure he looked plump enough to appear ‘healthy’. Despite detesting cigarettes, my grandmother smoked (but only in public and never inhaling, since it made her cough). She considered that smoking made her appear fashionable, and that was all that mattered.

Despite her complications and fastidiousness, Lilly was a good mother for my father—she was totally and uncompromisingly committed to him and adored him. On every possible occasion, in private or in public, she would say that ‘mein Pauli’ was the brightest, the best looking and the most impressive human being she had ever come across. Anything he said or did was instantly celebrated. Her devotion and admiration of my father, mostly seen as ridiculous by the outside world, had a lasting effect on my father. Throughout his life, he never once had doubts about himself or his abilities. The self-confidence that Lilly instilled in my father would prove to be enormously helpful to him as he ventured through a life that was often quite tumultuous. I wonder if he would have ever dared to start his own business, without an education, without financial backing, without significant contacts, if it hadn’t been for the ferocious self-assurance that Lilly’s attitude ingrained in him.

My grandfather Szigo was in many ways the exact opposite of my grandmother—relaxed, funny, someone who never took himself too seriously or thought too much about what others might think of him. Life was uncomplicated for him, and he was able to put up with a lot of grief, starting with his mother-in-law. Käthe, who had been totally opposed to her daughter’s marriage, took revenge on my grandfather on every possible occasion. Almost every day, and often in the presence of my father, Käthe would make trouble for Szigo. She invented stories about him, even going as far as telling the young Paul that his father was having extramarital affairs. But my grandfather somehow withstood the constant attacks and certainly Lilly never wavered in her love for my grandfather. My grandparents spent a happy and united life together.

Samuel led a comfortable life in Vienna, although he and his wife Johanna would be forced to emigrate in the late 1930s and would finish their days in the late 1940s in Buenos Aires. Johanna had 15 siblings, including two pairs of twins. She was the aunt of Paul Amadeus Pisk, who emigrated to the US in 1936 and became quite a well-known musician and composer. He studied in Vienna with a few of the most famous musicians of his time, including Arnold Schönberg and Anton Webern. Some of his compositions were played throughout the world, including the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires.

Samuel’s brother Max became a physician and quite a well-known public figure. After WW1 and until his death in 1920, he represented the Socialist Party (SDAP) in the parliament of Niederösterreich. Max worked at Vienna’s state hospital and from 1899 onwards also exercised additional duties in the insurance business, which led to frequent travel outside Austria.

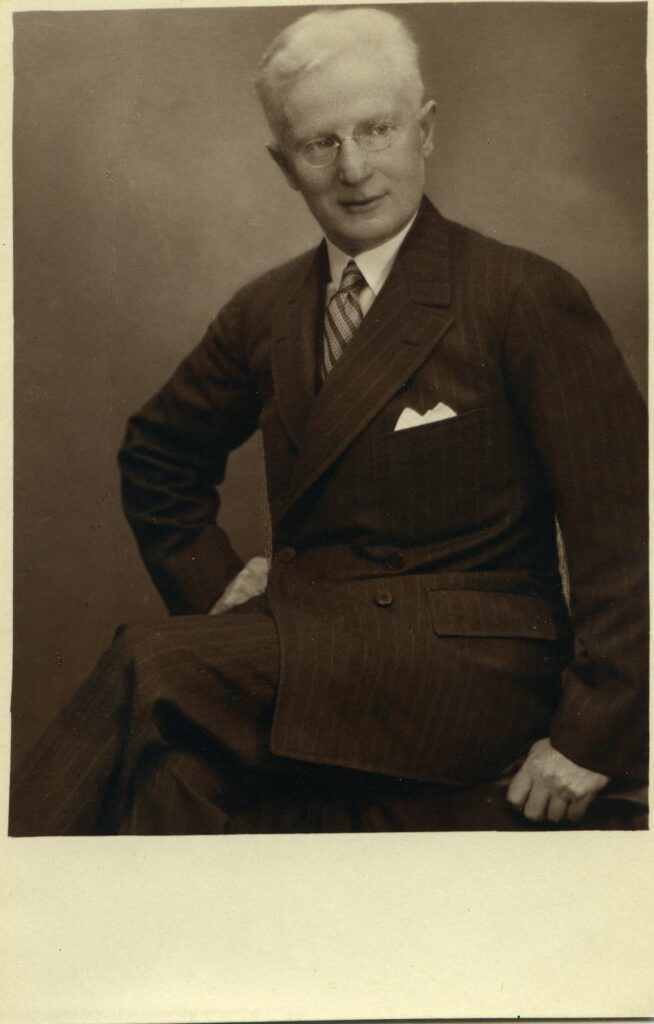

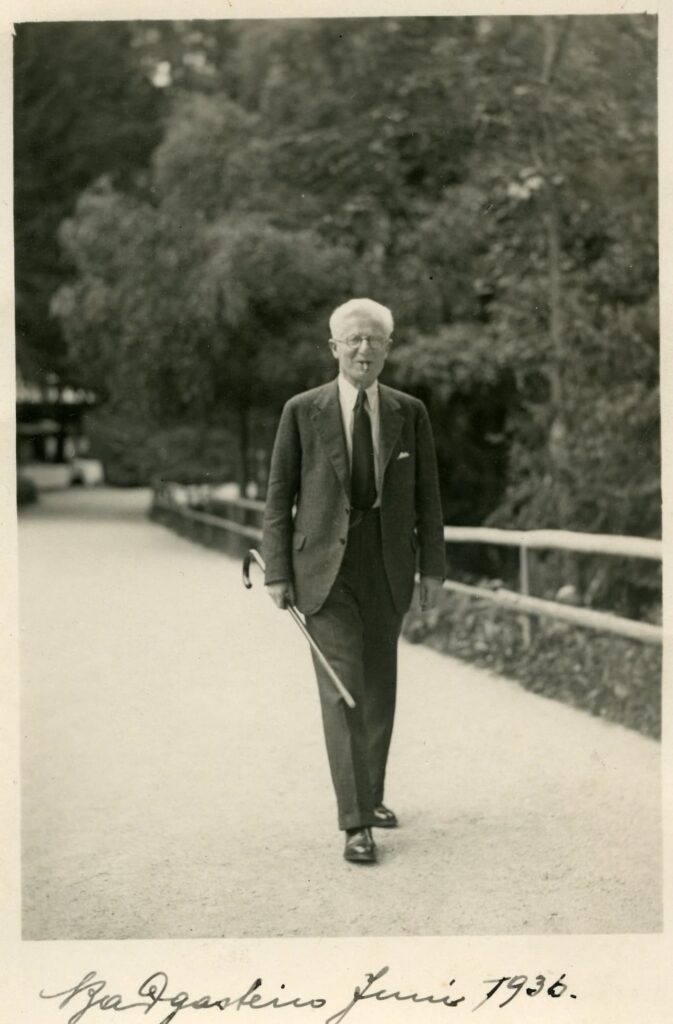

Dolfi and Lina, about whom little is known, finished their days in the UK, as did Eduard. Photos taken of them in the 1930s, show them as decidedly fashionable and well-to-do Viennese citizens. Dolfi, who I suspect was gay at a time when you didn’t want to tell anyone about it, seems to have spent a considerable amount of time in the very fashionable Bad Gastein. Eduard, who died at the age of 101 in Manchester, was an officer during WW1 in the cavalry, an honour that shows that he was particularly well positioned in Austrian society, where it was very uncommon for Jews to reach such status in the notoriously anti-Semitic Austro-Hungarian armed forces. The artistry of the photo and the evident pride that Eduard shows are a further indication of his standing in society. Eduard’s longevity meant that he visited us in Argentina around 1963, when he was in his 90s.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko