My parents, Paul Simko and Lisl Ellmann, met in Buenos Aires in 1947. Although they had both been born in Vienna, Austria, they would have almost certainly never come across each other in their native city—their families frequented very different social circles and lived at opposite ends of the town.

My father was immediately smitten by my mother. It wasn’t just her angelical, fragile look that attracted him. It was also her family that really fascinated him.

The Ellmanns are Ashkenazi Jews and, like the Simkos, most probably originate from the Kingdom of Galicia (an area situated between present day Poland and Ukraine, which until 1918 was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire). It’s also possible that their origin is in Moldova, in what is today north-eastern Romania, but their Galician genesis seems much more credible. Before settling in Galicia, the Ellmanns (and the Simkos) probably lived in Germany, from where most Galician Jews immigrated in the Middle Ages.

There has been much speculation concerning the first Ellmann for whom we have a record—Moritz, born in 1836. When asked, my mother said that she had heard that he was a doctor (of what kind, was unclear). Other Ellmanns I spoke to, said that he had been a wealthy businessman, a leader in the community of Braila, Romania, where we do know he lived in the middle of the XIXth century. In fact, we now know that Moritz was a tailor, a common occupation for Jews at the time. In fact, 80% of tailors in Galicia in the late XVIIIth century were Jews.

Whether Moritz was wealthy or not remains unclear, although if the life of Motel Kamzoil, the tailor in Fiddler on the Roof (my father’s favourite musical), serves as any indication, he probably scraped a living and that’s about it. He was certainly not a leading citizen in his community—there are no records indicating that he was anyone special, whereas other Ellmanns in Braila are mentioned in documents of the time. What we do know is that Moritz was married to Amalia Deutsch, born in 1847. They had five children: my great-grandfather Samuel (born in 1864); Max (1868); Eduard (1872), Amalie (Lina) and Isidor (Dolfi), whose birthdates are unknown.

Moritz is unlikely to have been born in Braila. There were only a few Jewish families living in this small town around the time of his birth, and all of them were of Sephardic, not of Ashkenazi, origin. Most probably, Moritz (with or without his parents, of whom we have no records) was part of a large group of Jews who settled in the lower Danube area in the middle of the XIXth century. Conditions for Jews in Galicia had hardened considerably under the reigns of Emperors Francis II (1792–1835) and Ferdinand I (1835–1848) of Austria-Hungary. At the same time, after 1829, the year it was reintegrated into the Principality of Wallachia, the town of Braila had become an attractive destination.

For the previous three centuries, Braila had been occupied by the Ottomans, and its role was a military, not a commercial one. From 1829 onwards, Braila (at the eastern tip of Wallachia) became a rapidly growing port, the place from which Wallachia and Moldavia’s considerable grain exports were shipped to the rest of Europe. Braila’s economic significance continued to increase throughout the XIXth and early XXth centuries, and its population increased more than twenty-fold between 1829 and 1900. Several Ellmanns are found in the area in the second half of the XIXth century, but their relationship to our family is unclear.

So, in the middle of the XIXth century, through a strange coincidence of destiny, your family and mine lived in the same country (Wallachia), only about 400 km from each other.

Sometime between 1868 and 1872, the Ellmanns moved from Braila to Vienna, with their children, Samuel and Max. Eduard, Dolfi and Lina Ellmann were born in Vienna.

So why did my ancestors move to Vienna only a generation (or less) after their arrival in Braila, at a time when this town and the region were booming economically? We cannot know for sure, but there are strong indications that their departure is above all a consequence of anti-Semitism, which resulted not only in a severe limitation of economic opportunities for Jews, but also in an environment of strong public hostility.

Romania’s first constitution, promulgated in 1866, explicitly stipulated that only Christians could be citizens of the new nation, which had been created a few years before through the merger of Wallachia and Moldavia. Only in 1919 would Jews be allowed to become citizens of Romania.

A report provided by the Romanian delegation to the first Zionist Congress in 1897 in Basel offers evidence of the harshness with which Jews were treated in Romania in those days. The report indicates that the 250,000 Jews living in Romania at the time ‘have no rights. They are only allowed to live in certain designated towns, they are at the mercy of civil servants, who not only treat them with contempt, but will not intervene if other members of the public harass them’. The report further indicates that about half of the Jews living in Romania at the time are ‘completely destitute’.

Surprised by the number of completely penniless Romanian Jews arriving in large numbers in New York in the last years of the XIXth century, The New York Times investigated the matter. This is an excerpt from the article the newspaper, published in October 1900:

It appears that the laws of Roumania are of such a character as to make it almost impossible for the Jews to remain there and provide a living. The Jews in Roumania …have extreme hardships which they are compelled to endure, they are practically disenfranchised. Much that is exceedingly humiliating and degrading to Jews is contained in the textbooks in use in the public schools, such, for instance as “A Jew never eats before he cheats.” “A Jew is a leech and lives on the blood he sucks from the poor peasants,” and “Never believe a Jew on oath, even when he is expiring”. Not only in matters of education, but in almost every walk of life the disability of the Jew is self-evident. He is not permitted to reside anywhere in Roumania except in one of seventy-one towns designated as abiding places for Jews, and he may be dismissed even from these on the representation of the police officers that his presence is undesirable. He is not permitted to follow the occupation of an apothecary, a lawyer, a stock broker, a member of the Bourse, the Stock Exchange, a peddler, or a liquor dealer. A still further impediment is found in the regulation which forbids employers of labor to give employment to a Jew until they first have employed two Christians, a ratio they must strictly follow no-matter how many they employ. All Government civil employments are denied to Jews, but they are compelled to do military duty under the conscription law, although equal advancement is denied them on the ground that they are aliens.

Not all Ellmanns left Romania at this time. Joseph H. Ellmann, whose relationship to our family is unclear, appears in the 1901 listing of Jews living in Braila. He must have been a banker, and prominent enough to become, in 1903, one of the founders of the Jewish Colonial Trust, the financial institution of Theodor Herzl’s Zionist movement, the offspring of which is today’s Bank Leumi.

It’s easy to understand why the Ellmanns chose Vienna as their new home. The 1867 constitution of Austria-Hungary for the first time granted Jews full citizen rights—they could reside anywhere they wanted, work in any area and practice their religion freely. The city of Vienna, the vibrant capital of what was then a peaceful, large and multicultural empire, was at the time run by the Liberal Party, which led to a particularly strong economic and cultural expansion. As a consequence of this very favourable environment, the Jewish population of Vienna increased from only 2,600 in 1857 to 147,000 at the end of the century, at which time Jews represented 12% of the Viennese population (from less than 1% half a century earlier).

Jews were now legally accepted in Vienna, but this was by far not the end of prejudice against them. The Habsburg bureaucracy detested them and very few made it into the ranks of the Austro-Hungarian administration. Within Viennese society as a whole, the apprehension, if not outright discrimination against Jews, by no means disappeared. Over the coming decades, as Jews prospered disproportionately from Austria-Hungary’s strong economic growth, they sought to ingratiate themselves with the Viennese public by investing heavily in the arts. Many of Vienna’s most emblematic and to this day most beautiful buildings, including the Burgtheater, the Volksoper, the Staatsoper, the Albertina, the Kunsthistorisches Museum, were financed by generous gifts of wealthy Jewish families.

There may be additional reasons why Moritz and Amalia chose Austria and specifically Vienna as their destination: if they or their ancestors did indeed originate from Galicia, they would have had many contacts with Galician Jews, who after 1867 became one of the largest groups to migrate to Vienna. My ancestors’ relocation to Vienna would have been greatly facilitated by the fact that Galicia was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, of which they were de-facto citizens. Indeed, Jews of Galician origin born after 1816 were considered subjects of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, so Moritz (born in 1836) would have had no problems settling in Vienna.

Whatever factors pushed them to move from Braila, we know that by 1872 at the latest (when Eduard was born), the Ellmanns were in Vienna. There, the generation of my maternal great-grandfather and especially that of my grandfather, did very well for themselves.

The Simkos are Hungarian Jews from southern Slovakia. My great-grandfather Josef Šimko (pronounced Shimko) is from Berencs (pronounced Bérench), Branč (in Slovak), a small town about 15 km south of Nitra, itself less than 100 km from Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia. His wife Regina Langer was born in the same area. They spoke Hungarian together.

Šimko is not a Jewish name. There are many Šimkos in the area of Nitra, but almost none of them are Jews. My ancestors originally arrived in Southern Slovakia from the Kingdom of Galicia, after this territory became part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1772. Today, Galicia no longer exists, its eastern area is now part of Ukraine, its western territory is part of Poland.

It was most probably Abraham Simko who moved the family to Slovakia in the late XVIIIth century. At the time, the family name was not Šimko. What appears to have happened, is that Abraham’s son Samuel, born in 1817, became the land estate manager of a local Slovak landowner called Šimko, and requested of his employer to allow him to use the name Šimko. Indeed, from 1788 onwards, Galician Jews had been ordered to adopt not only ‘fixed’ family names, but also surnames that should be distinctive enough, so as to ensure that they would be easily recognisable as Jewish. Mostly Jews were allowed to choose their own names, but sometimes the authorities chose names for them, and some of these were deliberately selected to be disparaging.

We know that Samuel and his family did retain their religious affiliation as Jews, but they would have felt relieved to carry a non-Jewish sounding surname like Šimko, especially if their original name was a degrading one.

Interestingly, even though southern Slovakia is populated primarily by Hungarians (a language and culture that my ancestors adopted upon arrival), they chose a Slovak, not a Hungarian surname. This strongly suggests that it was political, not ethnic, assimilation that became paramount to them. It also explains why my great-grandfather Josef gave such non-Jewish first names for his children: Ludwig, Sigmund, Sandor, Margit and Richard.

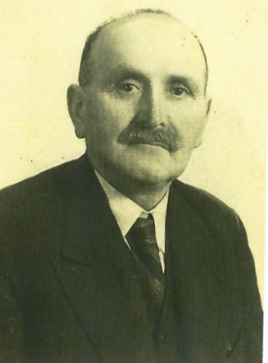

In any event, we know for sure that at the end of the XIXth century, Josef and Regina lived in Berencs, a very small town not far from Nitra, the region being at the time part of Austria-Hungary. The Šimkos owned a general-purpose store. Josef also developed a separate insurance business which was apparently, like his store, successful. They were quite prosperous. A photo from 1897 shows Josef as a young man (he was 26 at the time) and all the other Jewish Šimkos surrounding Samuel, the man who changed the family name to Šimko.

Around 1910 one of Josef’s competitors, apparently in an anti-Semitic act, burnt down Josef’s business. Josef had successfully sold insurance in the area, but for some reason had not insured his own business. Ruined and feeling under threat because of their Jewish origins, despite the Šimko surname, the family then moved to the capital, Vienna, with Ludwig (Lajos), Sigmund (Szigo, my grandfather, born in 1900) and Sandor (Shani). Two other children, Margit and Richard (Richi), would be born in Vienna.

Vienna provided a safe haven for the Simkos and they scraped a living for themselves, but they by no means did as well as the Ellmanns.

Josef became a Ratenhändler, a door-to-door salesman who peddled hardware (brooms, kitchenware, etc.) for families with very modest incomes. Payment was in quotas. This was a good system to acquire business, because the initial downpayment was very low, but it often proved difficult for Josef to obtain payment for the remaining quotas, once the material had been delivered. The friendly salesman was subsequently dubbed a ‘damn Jew’ when Christian families did not feel like paying what they owed him.

The Simkos settled in Vienna’s 20th District, one of the two areas (together with Leopoldstadt, where my father would be born), where most of the working-class Jews lived. Josef and Regina had a small, but comfortable apartment, where my grandfather Szigo lived until he married my grandmother Lilly, and where for many years, until my family left in 1939, the Simkos would congregate every Sunday.

My grandmother Lilly Karolyi was born in Vienna in 1904. She also came from a family of Hungarian Jews, who had settled in Vienna sometime in the middle of the XIXth century. Neither she nor her parents spoke Hungarian any longer and were very proud of their Austrian ‘roots’. My great-grandfather Abraham was an upholsterer. But, as he liked to tell everyone, not just any upholsterer. He was a königlicher und kaiserlicher Hoftapezierer, an upholsterer by appointment to the Kaiser. What probably happened is that one of Abraham’s clients from the nobility did not feel like paying him his dues in cash, so he arranged for a lofty title instead. What is certain is that neither Abraham, nor any member of his entourage, ever met the Kaiser and never worked for the royal household.

The Karolyis weren’t materially better off than the Simkos, but they thought of themselves as much more important people. This would create a lifelong problem for my grandfather Szigo, who was ostracized, if not outrightly harassed, by his mother-in-law, my great-grandmother Käthe (in whose apartment Szigo lived, and where my father was born). Considered by Käthe as ‘below the königliche & kaiserliche Karolyis’, she avoided all contact with the Simkos and Lilly only saw her in-laws sporadically. If we go by the only surviving photo of a Simko family reunion in Vienna, I can see why the Karolyis were put off by the Simkos—it was not in this manner that ‘prim and proper’ Käthe thought that a family should be photographed. You can sense Käthe’s sternness in this photo taken of her in the late 1930s.

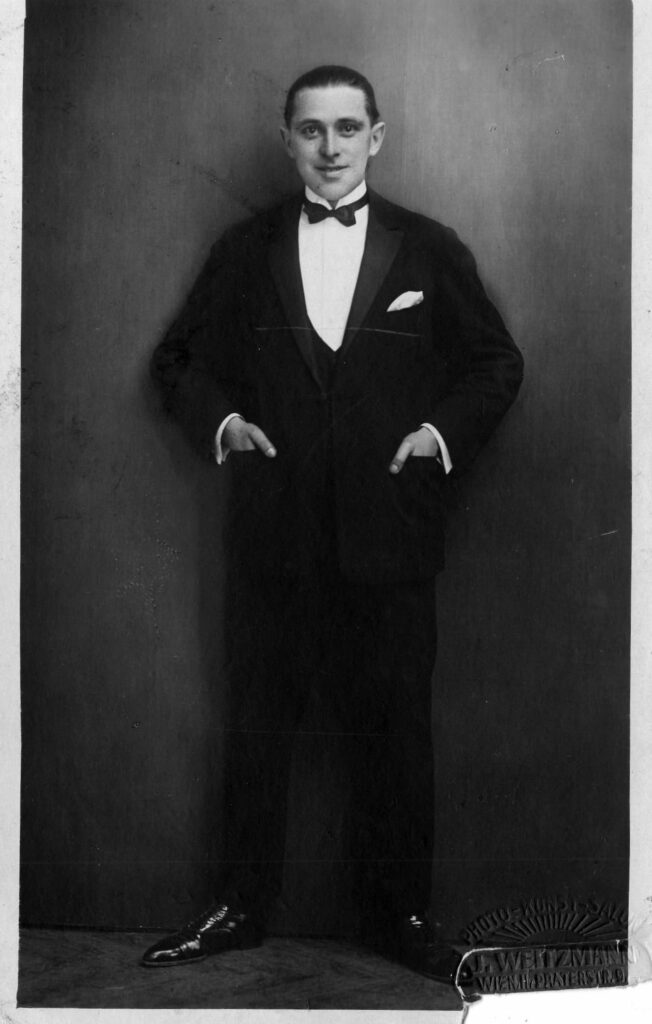

Nevertheless, my paternal grandparents had a happy marriage and spent a lifetime together. Szigo was an easygoing and charming man. He had met my grandmother Lilly after WWI. At the time, he worked as an Eintänzer, a ‘taxi dancer’—a man paid by dance schools to dance with young girls, a popular occupation for young men in an environment where there was a shortage of men following the end of the war. Only good-looking, charming, impeccably dressed and well-mannered men qualified for this occupation, so this tells us something about Szigo.

Apart from his job at dance schools, Szigo had another occupation immediately after the war: smuggler. Armed with his perfect command of Hungarian, he travelled to the Austro-Hungarian border at night, bought food and other necessities on the Hungarian side and re-sold them at a significant profit in Austria.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko