In the autumn of 1983, I was told by P&G that I was ready for Sales Training. At the time, promising Marketing Brand Assistants were sent for six months ‘into the field’ to experience what sales was like. Most Geneva marketing personnel that had qualified for sales training, had been sent to the UK, but I wasn’t able to because of the Falklands War, which had only recently finished, and Argentinian nationals were sill barred from the UK.

One day in late September, I was called into Samir Ayash’s office. A very tall, imposing Lebanese, who incessantly smoked a pipe, he reigned supreme over E&SO’s extensive global salesforce. He was a busy man, very conscious of his position, who usually never met with Brand Assistants, considered by him to be much below his level of management.

Samir went straight to the point: ‘We’ve found you a six-month sales assignment in Vancouver, Canada. You’re leaving in a week. It’s the very first time that we’re sending someone from Geneva over there. You better not screw up. If you do, it’s not only the end of your career at P&G, it’s also the last time that the Canadians will offer us a sales position in their country. I’ll be watching closely!’

Seven days later, on a Friday morning, I landed in Vancouver. There was no P&G office there, but I had a boss who lived in the surrounding area. I spoke to him on the phone, he told me that I had the weekend to find accommodation, and on Monday at 8am we would meet for an in-depth briefing. ‘Where can I find an apartment?’ I asked. ‘Well, just look in the Vancouver Sun,’ he said.

I did succeed in finding a one-bedroom apartment in the centre of town, on Pendrell St., only a few hundred metres away from Vancouver’s magnificent Stanley Park, where I moved in on Sunday evening, in time for my first meeting the next morning.

My boss was Western Canada’s regional sales director and had little time for me. He handed me over two large binders. One of them had the names and addresses of all the customers in my area, which included not only Vancouver, but also Victoria Island. In the east, my territory reached all the way to Hope, a two-hour drive from Vancouver. Getting over to Victoria Island required careful planning—there weren’t many ferries and if you missed the last one (because one or the other client was late, or the meetings took too long), you were stranded there till the next day.

The second binder included a description of the brands I was selling. It was a hodgepodge of products, from household cleaning products, such as Cascade, Spic & Span and Ivory Liquid, to (for me) totally exotic products such as Crisco Shortening, as well as a huge selection of Duncan Hines cake mixes and ready-to-spread cake frostings. I tried a few mixes at home and found them inedible, but apparently Canadians loved this stuff (or so I was told). At the time, P&G was struggling with Duncan Hines, and would eventually sell the business, but in 1983 high targets were given to me because I had arrived just in time for ‘baking season’ and ‘we’ve got the mixes that every mother will love to serve her family’.

The next day, I started on my sales tours. I would call beforehand, make an appointment and then arrive at supermarkets with the cheerful message: ‘Hello, I’m you’re new P&S Sales Rep, I’d like to show you the exciting new products we have for you this season!’ Most of the shop owners received me with a bemused look and said: ‘Oh, it’s great you’re here! Before we talk about anything else, come with me, I have something to show you.’ They would then take me to their back room and point to the piles of P&G boxes they had in storage. ‘Find a way to sell this stuff before we talk about any other business, OK?’ one client after the other said to me.

Two weeks after my arrival, I called my boss. I said that I had visited over two dozen clients, large and small, and that it was impossible to sell in my area—every shop was clogged with products that my predecessor had sold in before leaving. Apparently, he had significantly increased the orders in order to cash in on a bonus.

‘That’s your problem, Pedro,’ my boss said. ‘You have your sales objectives, you need to achieve them.’ Then he hung up.

Images of Samir Ayash started to appear in my mind at all moments of the day. And during the night, I would wake up sweating, with Samir Ayash’s words ‘you better not screw up’ pounding on my head.

I felt very lonely in Vancouver in the initial weeks, and this, together with the work pressure, contributed to spells of insomnia, which only made things worse. I stopped running, despite being beside a beautiful park.

I knew no one. I couldn’t call anyone (it was far too expensive to use the phone for international calls). And in the time before the internet, if you didn’t have local contacts, you were totally isolated.

On one of my first weekends, I went for a walk in Stanley Park. The weather was still nice and there were lots of people around. I got into a conversation with a woman who was kind and friendly. She looked a bit older than me (in her 30s, I thought) and we arranged to see each other the following Saturday. When the day came, I went to her home to pick her up. But when I arrived, I realised that she was in fact much older than me (probably late 40s). While ‘my date’ was getting herself ready, her daughter, who was in her 20s, showed up and said: ‘So you’re my Mom’s new boyfriend!’ I was terrified. While both were away for a moment, I went to the door and just ran away.

This incident showed how desperate I was to make contact with people in Vancouver. I did, over time, get to know people I liked, but it was a slow process. Short-term, I decided to concentrate on my work.

Most of my clients were tough, but kind. But some others were less so. On one occasion, I travelled to Hope, about 150 km from Vancouver, to see the manager of Buy-Low Foods, at the time the largest supermarket in this middle-sized town. The only time he said he could see me, was on a Monday at 7am. So I got up at 3.45am, left home at 4.45am and arrived just in time for my meeting. After waiting for about an hour outside in the cold, an employee appeared, who told me that the boss would not show up that day. No other time was proposed for my meeting and no explanation was given for why the manager had not appeared.

Until my time in Vancouver, I had always lived in environments that had been kind to me. I had loving parents, and a family that had always encouraged, if not celebrated me. Wherever I had lived, I had been surrounded by friends. I had attended great schools and, at P&G Geneva, the fact that I had been to HBS and Princeton, meant that everyone treated me with great respect. Whenever I opened my mouth, people would listen.

Now I was surrounded by people who didn’t know where I came from and couldn’t have cared less. I was one of many salespeople trying to peddle their stuff to young managers, who were often overwhelmed by long working hours and for whom I was not so important. It was a tough and unforgiving environment, a wakeup call for me. I realised in what a pampered environment I had lived until then. During my six months in Vancouver, I grew up tremendously. It was a formative experience that I never forgot and that helped me for the rest of my life. From this time onwards, I never again took kindness for granted. Many years later, when I started my own business, my time in Vancouver helped to become mentally fit for the coldness and indifference of the real business world.

After weeks of feeling tense, tired and overwhelmed, I gradually calmed down, and started to look more carefully into the business agreements we had with our clients. I discovered that the largest volumes were generated by clients that were part of national supermarket chains. For every case that was sold in my area, an ‘advertising’ contribution was paid by P&G to the clients’ headquarters. This was money used by the supermarket central offices to fund national advertising campaigns. But none of the contracts I examined explicitly said that P&G’s contribution had to go to the national headquarters. Apparently, it was ‘customary’ to do it this way, and nobody, in decades, had questioned the system.

So, I went to see my largest clients, those that were part of chains, and told them that from now on, the money that P&G was paying to the ‘national advertising fund’, would belong to them. The funds could be used to advertise in the local press to push for their local business, vs. disappearing somewhere in Ontario in some ‘national’ fund.

The surprised clients double-checked the contracts and agreed with me that what I had in mind was perfectly ‘legal’ and a great idea for their business. I started to contact the local media. I would write the advertising myself, advise the clients where to place the ads and book them in local newspapers or on the radio, or sometimes produce flyers that were distributed door-to-door. Soon the P&G business in my area started to explode. The more the clients bought from me, the more their ‘advertising fund’ would grow, so most large clients started to free up large spaces inside their shops to showcase P&G products that offered particularly large contributions to the advertising fund.

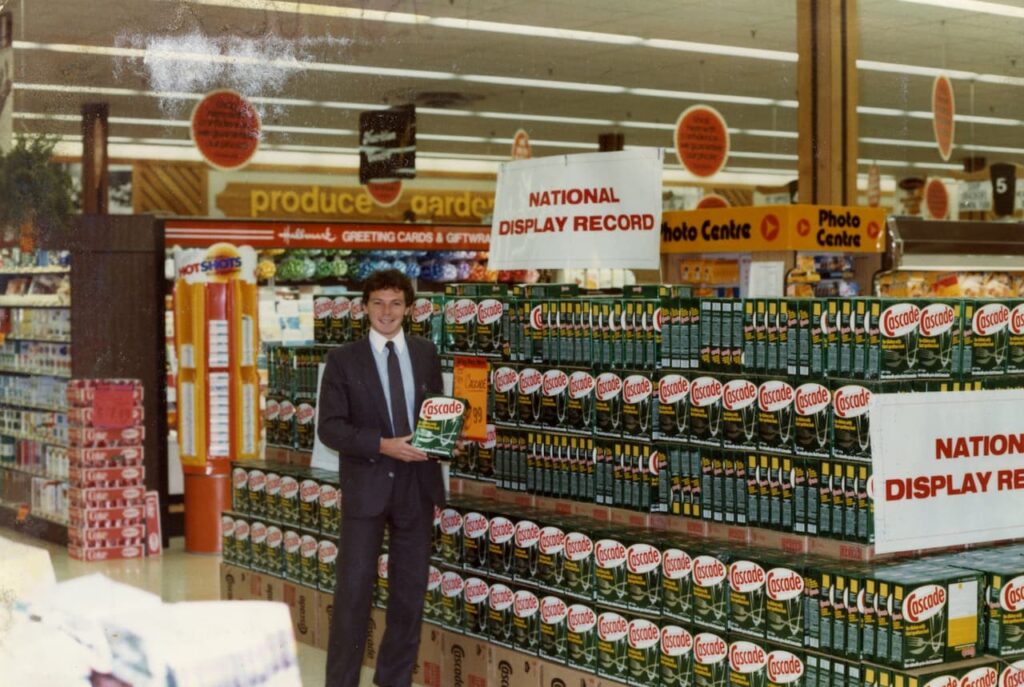

I said nothing to my boss about this. After about two months I received an urgent message. Could I please call my boss on a certain day, at a certain time. On the agreed date, both he and his boss (the Canadian Head of Sales) were on the phone. They had seen my sales numbers and wanted to know what was happening. ‘What exactly do you need to know?’ I asked. ‘Well,’ said the big boss, ‘you have a small area, but over the last two months, your sales have been the highest of any sales representative in all of Canada. In fact, you have sold so much in some stores that you qualify for National Display Record Awards. You’ve earned not one, but three awards in only one month. We’ve never had this in Canada before, no salesperson has ever won three awards, let alone in the same month. And no one, in the history of Canada, has ever won such an award in British Columbia. Usually, these distinctions go to sales reps in Ontario or Québec, which are much larger territories’.

I then explained what I had done with the advertising fund. There was a long silence. Then the big boss started to laugh and said: ‘You sonofabitch, you are right, there is no obligation for P&G to pay this money centrally. What do we do now? The people in our clients’ headquarters will eventually figure it out and will put a stop to it. But you know what, that’s my problem, you just keep going Pedro, sell them what you can and keep the local advertising going. Oh, and tell this guy Ayash, to send me a few more Pedros!’

My assignment finished a few weeks later. When I told my clients that I was leaving they couldn’t believe it. Some asked whether they could write to ‘someone’ so ‘Pedro can stay a bit longer’. Others asked if I could continue writing their advertising, even if I was in Geneva. Many invited me to dinner and gave me goodbye presents. I later heard that a few months after my departure, most supermarket headquarters realised what had happened and the local managers in British Columbia were not allowed to keep the advertising funds for themselves any longer. But in one case, the loophole became the rule: Overwaitea, under pressure from their outlets in British Columbia, from then on decided to disband the central advertising fund and allow the local supermarkets to advertise on their own. For years thereafter, I would receive a Christmas card from the Overwaitea Vancouver manager—each time he thanked me for what I had done for his business and for Overwaitea as a whole, which apparently grew faster than its competitors in the following years.

Apart from work, Vancouver allowed me to make two great discoveries: Chinese cooking and cross-country skiing. In early January, while reading the local press, I stumbled upon an ad, inviting people to enrol in a Chinese cooking course. Conveniently for me, the course was on Saturdays. So, during my last weeks in Vancouver, every Saturday I joined a group of six or seven people (none of whom were Chinese, not even the teacher). We would go to Chinatown, buy exotic-looking food, and then cook together in the teacher’s apartment. It was a lot of fun, and I returned to Geneva with many recipes, all kinds of weird spices and a huge, steel iron wok.

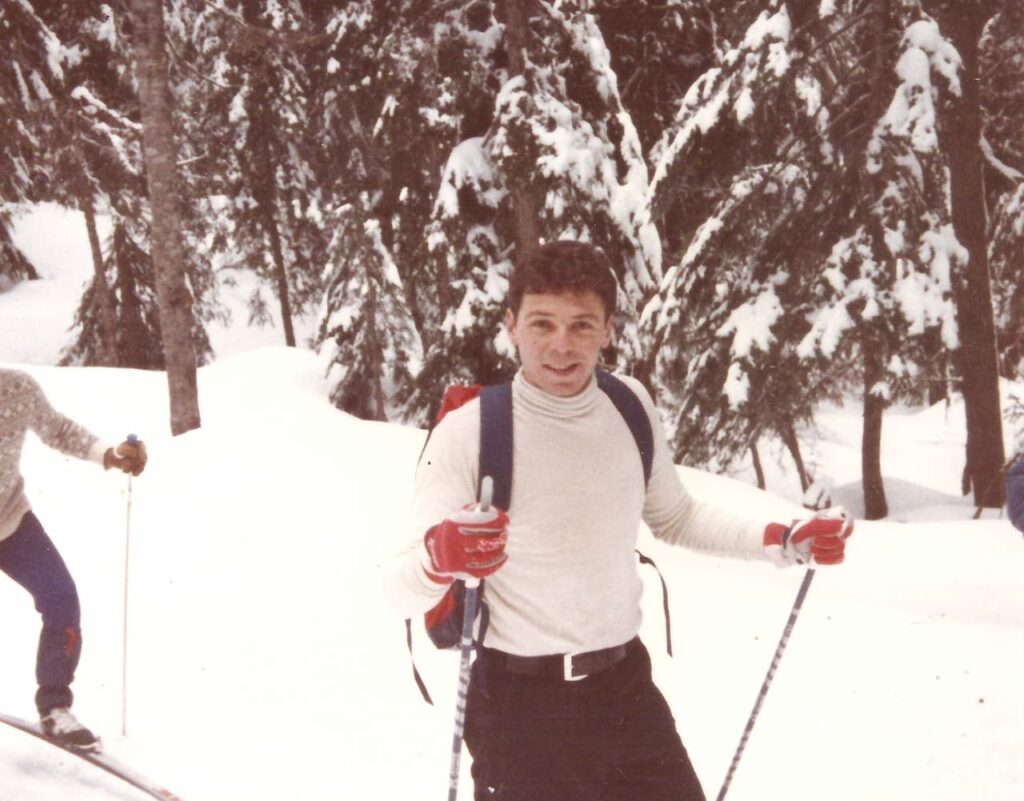

Vancouver is covered with snow in the winter and a paradise for cross-country skiing. While there, I bought my first equipment, took two or three lessons and initiated what would become a lifetime love-affair with this sport.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko