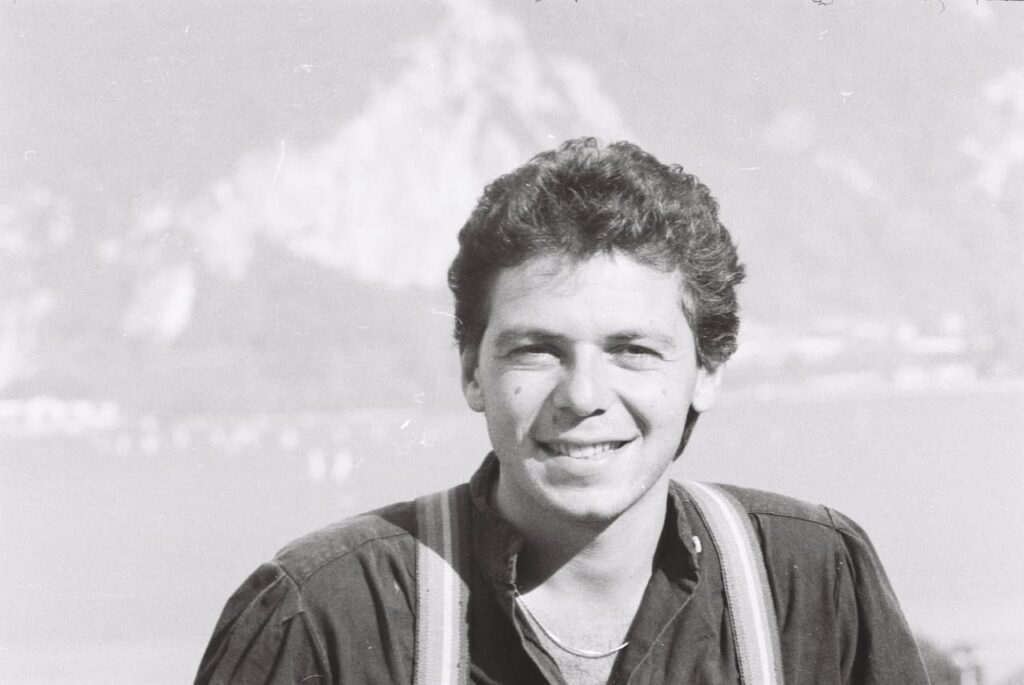

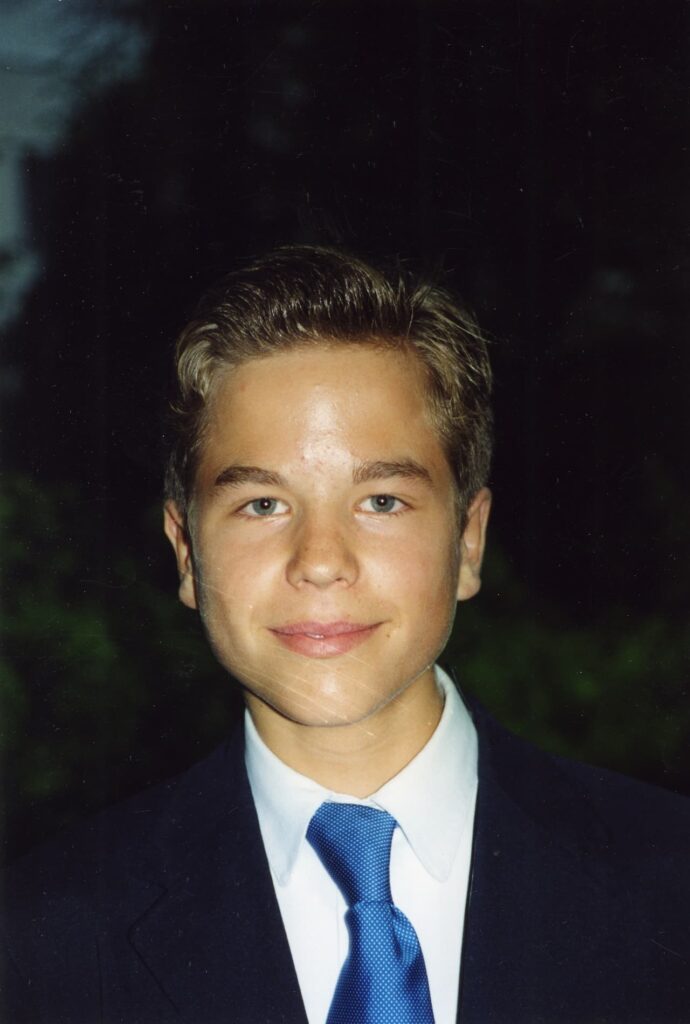

My next boss was Ramesh Vangal. John Langdell had been quiet and relaxed, with lots of time for me—perfect for my first few months at P&G. Ramesh was his exact opposite, a thunderstorm. He was in charge of Kuwait, at the time a rapidly growing and important business for the company. The team was also larger: Ramesh already had an assistant, Michel Recalt, of mixed Cuban and French descent. Both Ramesh and Michel would develop stellar careers beyond P&G in the years to come. In early 1983, however, they were two hungry wolves, trying to prove to the world how excellent they were.

Before leaving, John had rated me as ‘outstanding’. In the very competitive P&G environment, this was a very serious endorsement. At my first meeting with Ramesh, he said: ‘So I hear that you walk on water. Fine. Let’s see if you really do.’

Two days later, I was on a plane to Kuwait, with a long list of issues to ‘push through the distributor’ and three days to do it.

I arrived in Kuwait on a sunny morning and headed straight to the distributor’s office, arriving at Ali Abdul Wahab (AAW)’s office before 8am. The person in charge of P&G’s business at the time was Tawfiq Abu Rabie, a quiet, introverted man.

At the reception, the night porter gave me a puzzled look, then informed me that Mr. Abu Rabie would be in ‘any minute’. About four hours later, Tawfiq finally arrived. After a short introduction, I presented him with the long list of items that Ramesh and I had put together, told him that I wanted to go through them one by one, and leave with signed agreements, a detailed plan of next steps and clear, measurable progress benchmarks going forward. ‘We have two full days to do this,’ I said with a smile.

Tawfiq, who hadn’t quite sat down yet, looked at me straight in the face, and for a while said nothing. Then he stood up, went to his cupboard and took out a small rug. ‘What are you doing?’ I asked. ‘I need to pray,’ he said, rolled out his mat in a corner of the office, knelt down and began the Dhuhr ritual. I didn’t know what to do. Should I stay? Should I leave? In the end, I just moved my chair a bit to the side and watched in silence.

As soon as Tawfiq had finished, I started again: ‘So with which item should we start, Tawfiq?’ I asked. ‘It may be best to tackle the biggest issues first. Here, let’s talk about what to do about the Tide business. I think it would be wise to drop prices on the two smallest sizes, this will ensure a broader distribution,’ etc. After I had finished my discourse on pricing, including the pros and cons of doing this or that, Tawfiq stood up and said: ‘I will have lunch now,’ and left the room.

I waited for Tawfiq to return. He did, for about an hour at 5pm. By then, I was worn out, extremely irritated and tired. Our meeting was very short. Tawfiq just said: ‘Let’s talk tomorrow.’

The next day we met for about an hour. After I once again tried to go through my ‘to do’ list, he asked me how I liked working at P&G. I said I loved it, but that we had work to do. ‘Let’s concentrate on this,’ I said. And whether Ramesh was in good health, he wanted to know. ‘Yes, yes, Ramesh is doing fine.’ ‘And what about Michel, how’s his Arabic coming along?’

My flight was on Day 3 in the late afternoon. I was determined to get through my list of items, at least through some of it. But Tawfiq wasn’t around. After a few hours waiting, I was told that he would be spending the day at Al Jahra, a town about 20 km from Kuwait City. So, I left for the airport.

When I returned to Geneva, I didn’t have to wait to see Ramesh. He showed up in my office the moment I arrived and said: ‘We need to talk.’ He then explained to me that Tawfiq’s boss’s boss, the owner of Ali Abdul Wahab had called the CEO of P&G’s Geneva operation, and had asked for ‘this Harvard man’ to be given another assignment. I was considered ‘inappropriate’ for doing business in Kuwait.

My reaction was swift. I asked Ramesh if I could return to Kuwait. ‘What do you mean?’ he asked. ‘I’d like to return,’ I said. ‘When?’ ‘Now.’ Ramesh stood there with his mouth open and I added: ‘There’s a plane leaving for Kuwait in two hours. I’d like to take it.’

The next morning, after landing in Kuwait, I went to the hotel, took a shower, put on a white shirt with no tie (I had continuously worn ties and a blue jacket previously), and headed for the AAW office. When I arrived, I said that I wanted to speak with Mr. Abu Rabie. I’m looking at the schedule, said the assistant, we were not expecting you today. ‘I know,’ I said. ‘I’m not sure if Tawfiq has time,’ the assistant said. ‘It doesn’t matter,’ I said, ‘whenever he is available, I know how busy he is, I’ll just wait.’

I waited for about three hours. Then I was escorted into the office. ‘I’m here to apologise,’ I said. ‘I’m very sorry for my behaviour in the last few days. This is my first job, you know, and it’s also my first time in the Gulf. I have a lot to learn. If you and your colleagues would give me another chance, I will do my very best to learn and, who knows, perhaps I could be of some help to you.’ I then stood up and left.

Nothing happened the next day.

But on the third day, I received a message in my hotel. Would I like to join Tawfiq for lunch?

Tawfiq and I spent a very long lunch talking about our families. He wanted to know if I had brothers and sisters, what they did in life. He asked whether my father was in business, and where he came from. I told him about Vienna and about my Jewish origins. ‘Ah’, said Tawfiq, ‘so we are cousins!’ He then told me his own story. He had grown up in Jaffa, what is now Israel, and was forced to leave his home in 1948, when he was a child. After many stops, he and his family had landed in Kuwait. He told me about his family’s orchards in Jaffa and their business selling oranges. He said that the hardest part of his exile was not being able to know what had become of the orchards. His wife was from Beersheba, also now part of Israel. They had met in Kuwait and had three children. ‘Every evening at dinner we sing the songs of our homeland,’ Tawfiq said, ‘so the children don’t forget where they come from.’

The next morning we met again, this time at the office. I asked Tawfiq a few more questions about his family and then, at some point, he said: ‘So about this Tide business that you are concerned about, I think that there’s two or three things we could do.’

From then on, I visited Kuwait many times and slowly, step by step, Tawfiq and I covered the items that had been on the initial list that Ramesh and I had put together. It took many months to get everything done, but the business grew and by October 1983, when my assignment on Kuwait had ended, I had earned another ‘outstanding’ rating, this time from Ramesh. And I had learned a fundamental lesson: if you want to be successful in business, you need to start by understanding who you are dealing with, respect where they are coming from and adapt to their cultural needs.

Tawfiq and I became good friends and I was invited several times to his home. I met his wife and his children. After a while, I learned a few words of Arabic and would make them laugh. They touched me profoundly with their simplicity, their honesty and their love for each other. I still remember their songs, which they always sang before the meal started, while holding hands with each other. Like so many other Palestinian families, the Abu Rabie’s were forced to leave Kuwait in the aftermath of the 1991 Iraqi invasion. Sadly, I completely lost track of them afterwards.

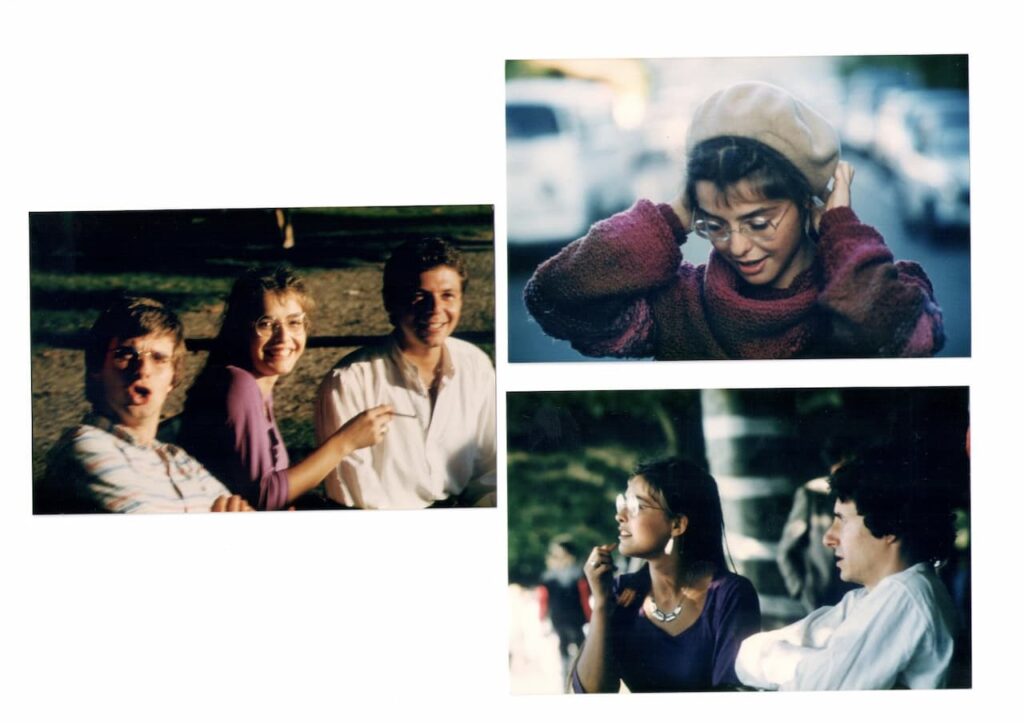

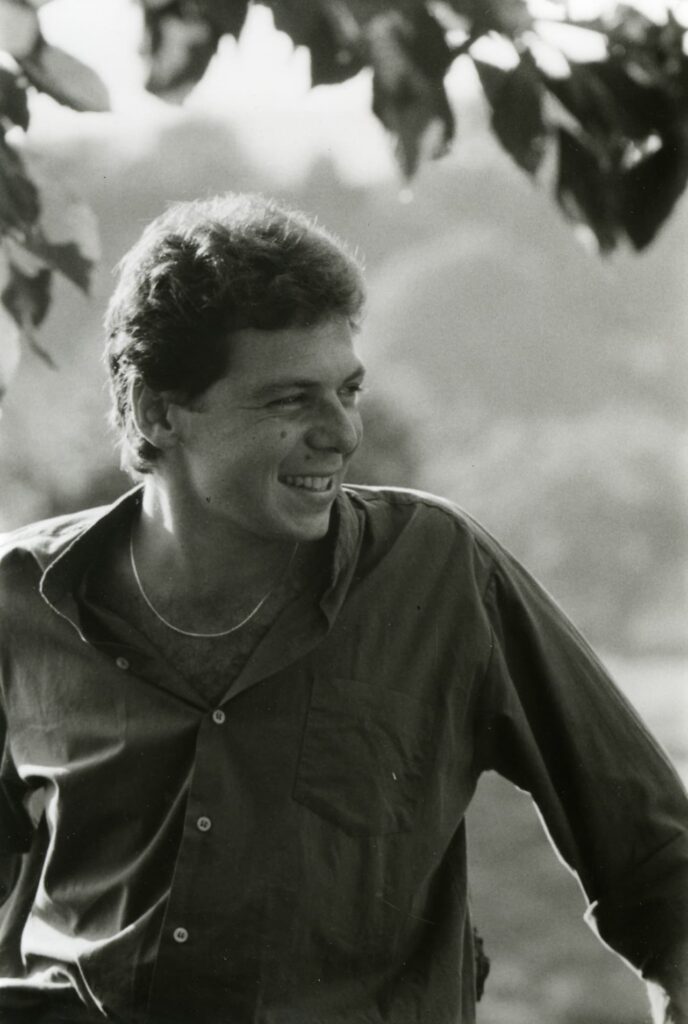

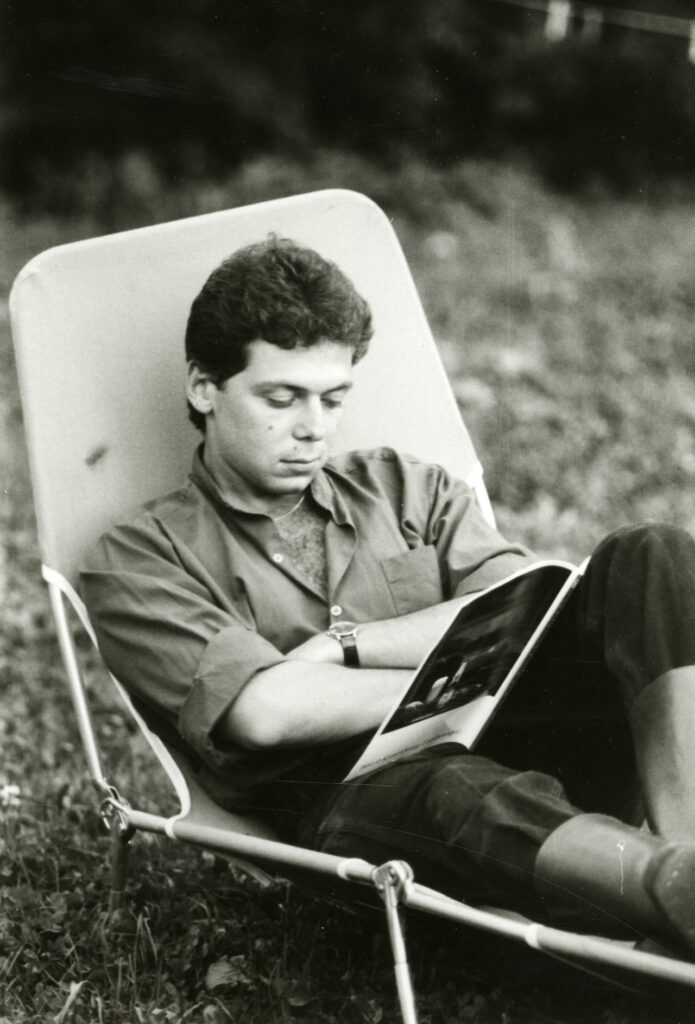

Despite my heavy travel schedule (I was now spending about half of my time in Kuwait), I maintained a very active social life in Geneva, with frequent trips to the countryside, wonderful meals with friends and a few romances. Fer had meanwhile met Brigitte, who would become his first wife, and the three of us frequently spent time together.

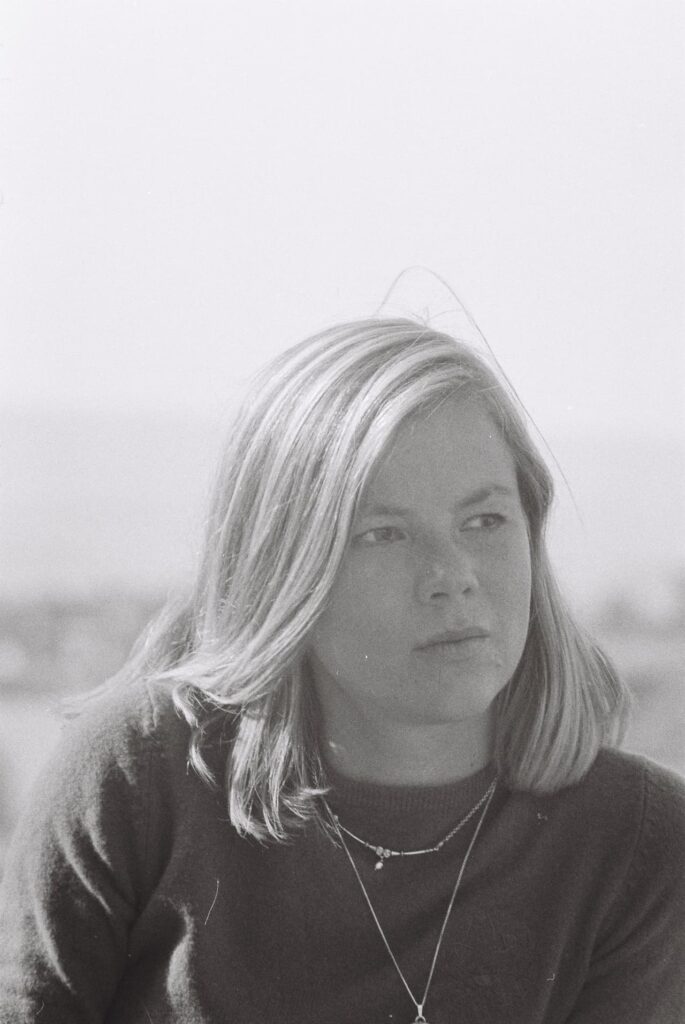

It was also during the summer of 1983 that I met Kerstin, who would remain a lifetime friend. From Germany, Kerstin came to Geneva to take a few courses at the university. We travelled together extensively, and she helped me to considerably improve my German language skills. She had a wonderful diction and read enormously. I owe my discovery of Thomas Mann, Hermann Hesse and Günter Grass to her. Later, I would become the godfather of Carlos, her third son, which further consolidated our friendship.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko