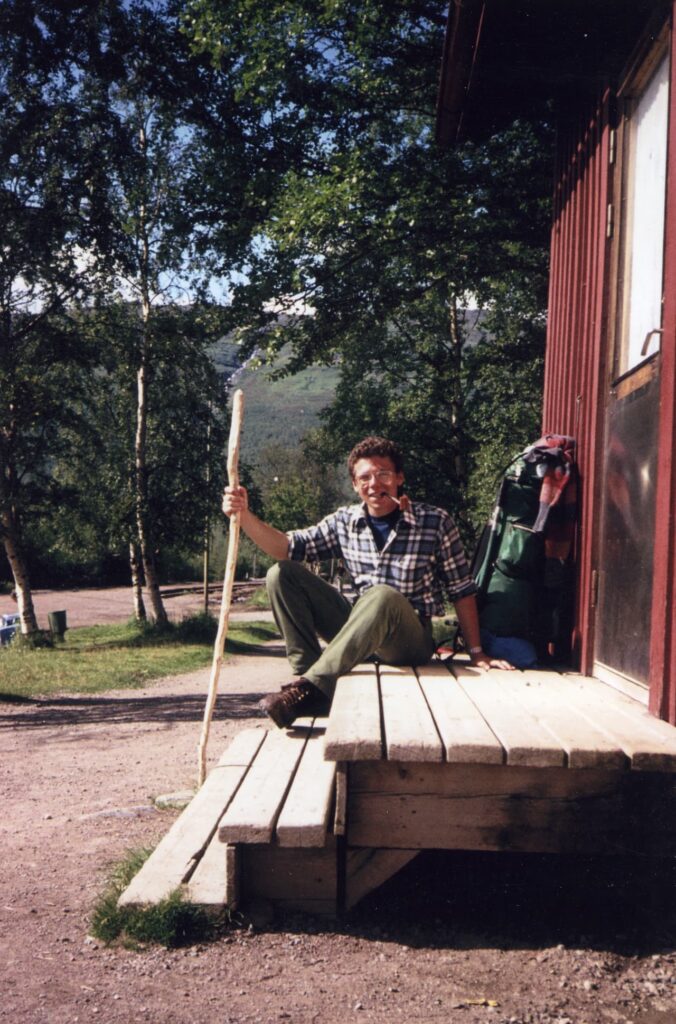

Scandinavia, where I spent the summer of 1978, exercised a unique attraction on me. I loved the freedom of the Nordic people, their strong sense of honesty and their democratic values. In the summer of 1978, I saw many of the Scandinavians I had met in Greece in 1977. I travelled to Nordkapp, the very north of Norway, which at the time was only accessible by boat. I loved the fjords, the majestic blue sea and the introverted, but welcoming people living in this part of the world. As preparation for my trip, I bought a Norwegian grammar book and studied travel guides, some of which were from the XIXth century, that I discovered at Firestone Library. By the time I got to Scandinavia, I was able to communicate quite well in Norwegian, and to decipher their newspapers. I travelled with a tent and cooked my own food (restaurants were prohibitively expensive in the Nordic countries at the time).

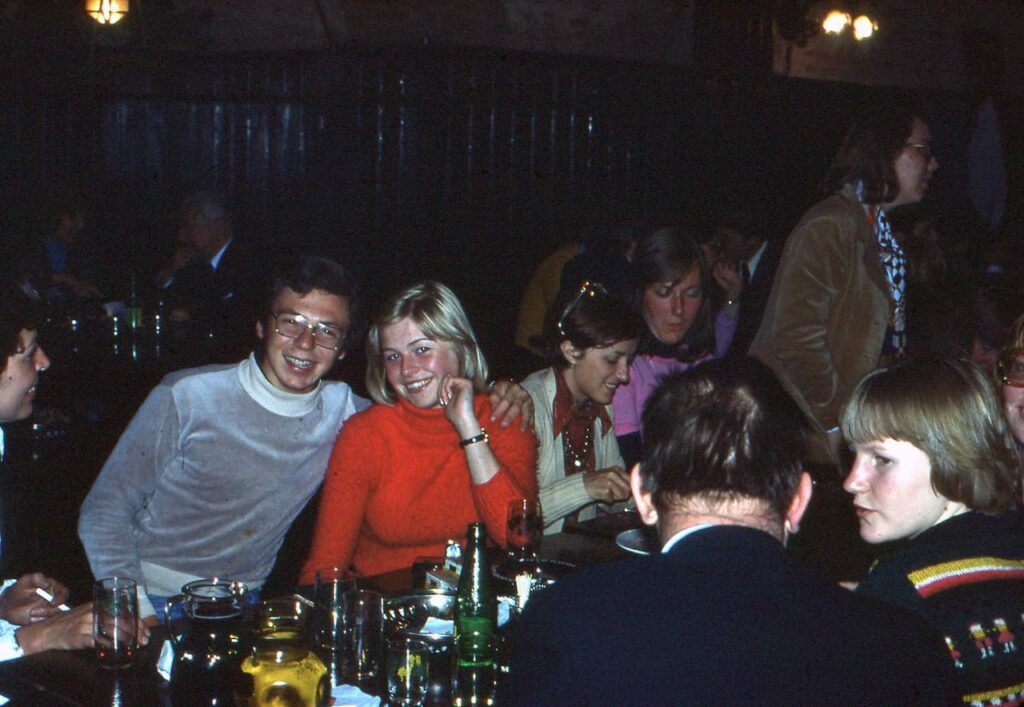

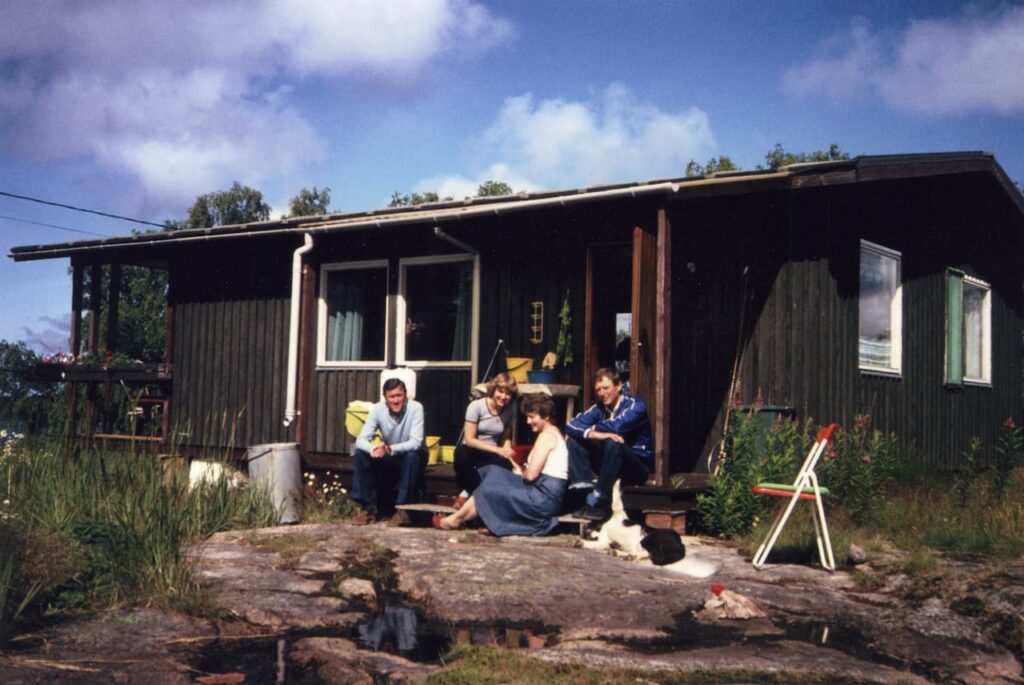

I spent about ten days with Kirsten in Denmark. We rented a canoe and travelled down numerous rivers, camping in the forest. It was mostly rainy, but we had a very good time. It was the third summer since 1975 that I had seen Kirsten, and she thought the time had come for me to meet her parents. I had no idea what family she came from until, on a Sunday morning, I rang the doorbell of a very fashionable home with a large garden in the outskirts of Copenhagen. A man in a blue blazer and a tie opened the door and I realised immediately how inappropriately I was dressed. Kirsten’s father was at the time the President of Danske Bank, and one of Denmark’s best-known businessmen. He was formal and very conservative, and I felt totally out of place in their grand home. Luckily, Kirsten’s mother, who was also exquisitely dressed, was a lot more relaxed and livelier. She did her best to put me at ease. But I did feel ashamed of myself, with my long hair, my little round glasses, my wooden clogs and my yellowish-white workman’s shirts with puffy sleeves. I would again make the same mistake of dressing totally inappropriately a few later when I had lunch with the Prime Minister of Norway.

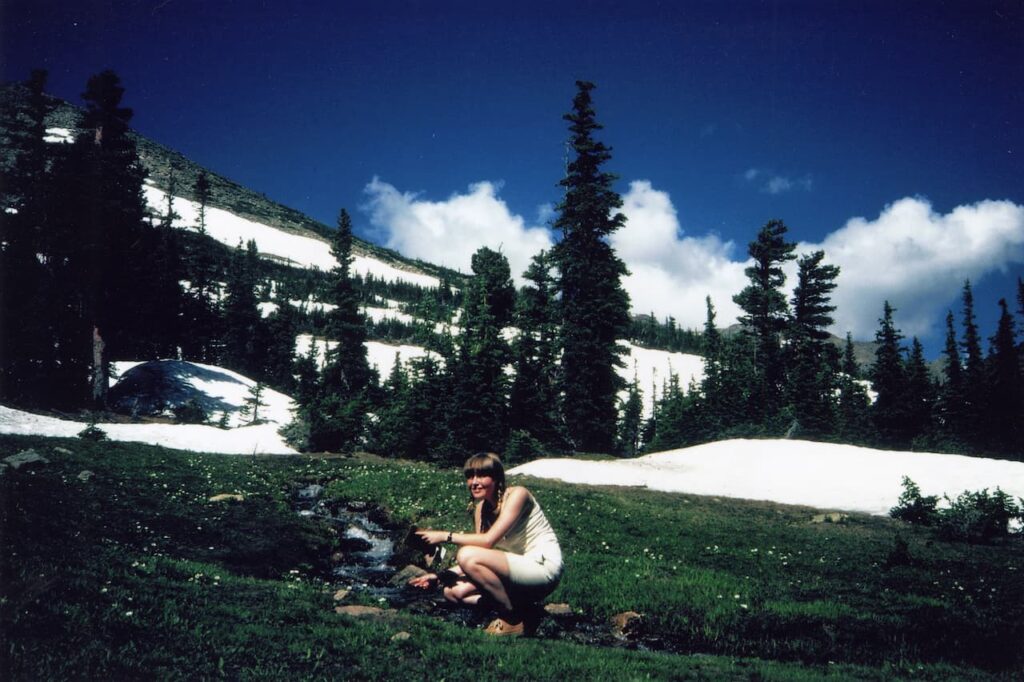

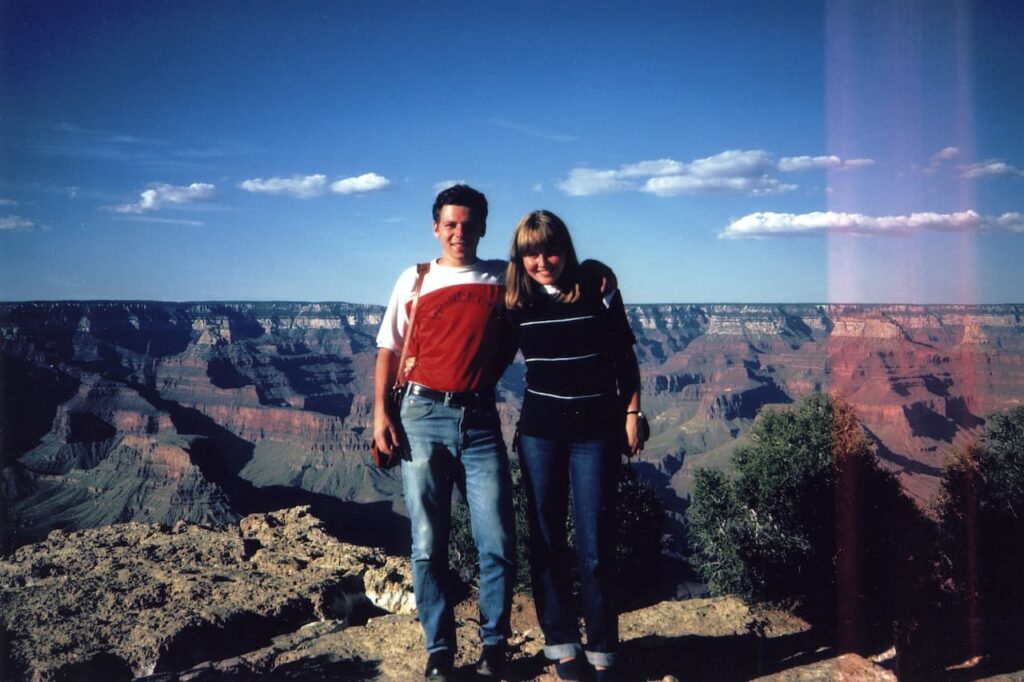

Kirsten and I got along well. She was very bright, enterprising, and we shared a strong interest in discovering the world. She also had the means and the time to travel. We decided during the summer of 1978 to spend the next one traveling throughout the US.

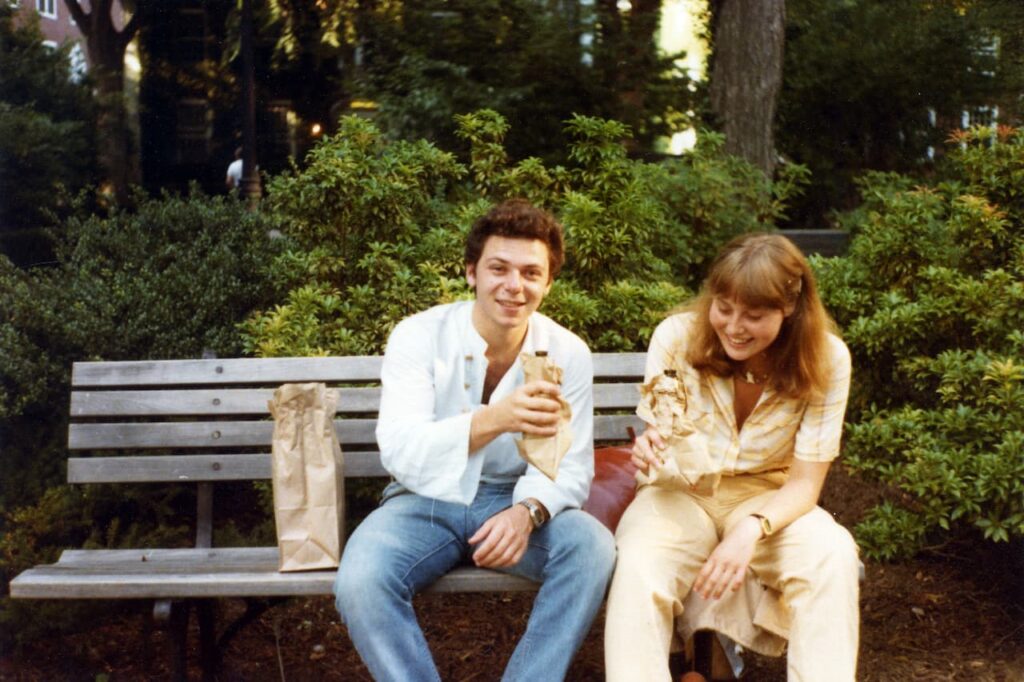

We bought a Greyhound ‘unlimited travel’ ticket and crisscrossed the US. Mostly, we slept on the bus, but I carried with me the tent from the previous summer. At other times we stayed in motels or with my college friends, many of whom we stopped to visit. It was my first experience seeing the US beyond the big cities of the East Coast, and I was not very impressed. The towns, the people, mostly appeared banal, superficial and looking all the same to me. And the food was terrible.

When the time came to choose a major, I set my heart on the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. Apart from the fact that international affairs had always been a subject that had fascinated me, Woody Woo (as we called it) had research facilities that were extraordinary, high faculty dedication and a system of preceptorials and study groups that was very attractive to me. Also, it was the department with the largest international focus and, last but not least, I knew that its students easily obtained funds for field trips. But it was the only department for which an application was necessary, and the selection process was very rigorous. I was accepted and did, indeed, spent two very happy years there. I made full use of field trips, including a memorable one to Luxembourg, to visit the European Parliament, which turned out to be more of a drinking and tourist excursion than a serious academic endeavour.

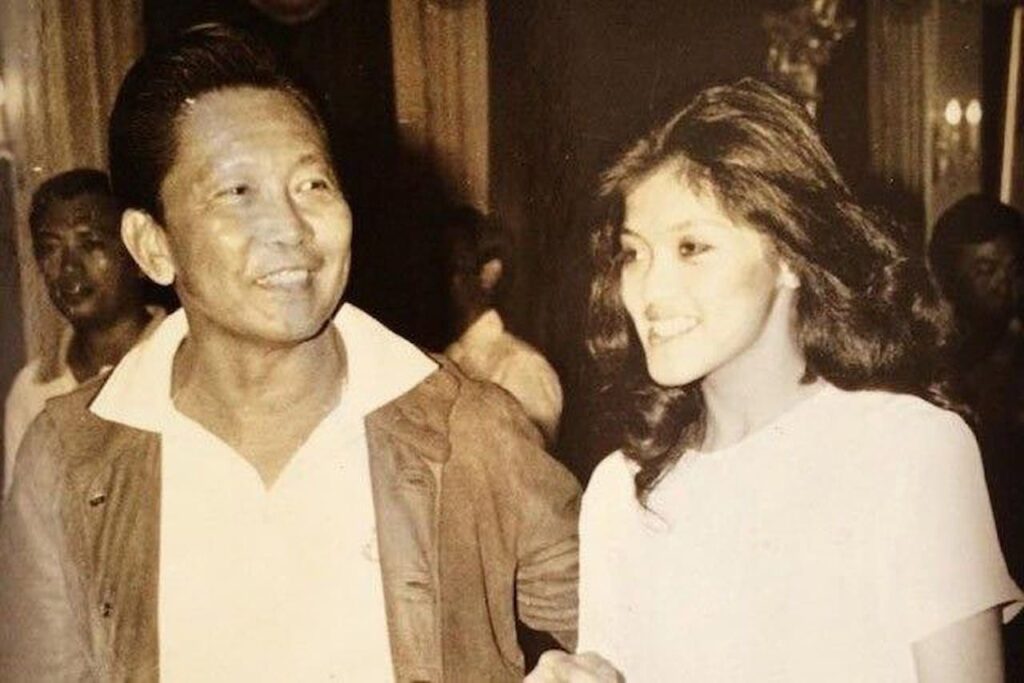

During my third year at Princeton, I met a rather tall girl, with long black hair and an exotic look. We were both taking the course ‘Cuba in the 1970s’, a late afternoon weekly seminar, attended by only six or seven other students. Imée didn’t always do her homework and, accordingly, sometimes had nothing to say during our class. Sometimes she didn’t show up at all. But when she was there and had done the readings, she was brilliant. She could make connections that none of us had thought of—how Angola influenced Cuba, the political evolution of Mozambique and its impact throughout Latin America, the revolutionary experience of the Congolese and what it meant for Cuba. She reflected on the internal power struggles of the Cuban revolutionary leadership. She could speak at length about Che Guevara. And on one occasion, she mentioned her own experience visiting China’s countryside. Mao’s China, I thought, how could she have visited the place? It was a country that no one, not even the world’s best-connected people had ever seen. How had she ever gotten in? I was intrigued.

So, one evening (the class finished at about 6.30pm), I invited Imée to the pub, which was just next to the classroom in which we met. We had one beer, then another and then I asked her where she was from. ‘The Philippines,’ she said. ‘Ah,’ I said, ‘I come from Argentina.’ We then exchanged a few words in Spanish. After a while, I asked her what her family did there. ‘My Dad is the President,’ she said. ‘Ha, ha,’ I said, ‘my Dad is the President too, he’s the President of Simko SA!’ We continued talking and then I suddenly asked: ‘What’s your family name?’ ‘Marcos,’ she said. And then it hit me: this is the daughter of Imelda and Ferdinand Marcos, one of the most charismatic (and hated) dictators of the 1970s. Imelda was world famous for her extravagant lifestyle, including thousands of pairs of shoes, in an impoverished country.

From this evening onwards, for several months until the summer holidays, I saw Imée often. She lived off-campus and was always surrounded by half a dozen security guards. She was far removed from a normal campus lifestyle, had a car and a chauffeur, a maid and a cook. A few Saturdays we would see each other at her place and then she would spontaneously say: ‘Let’s go to New York!’ We would leave at about 10pm and invariably wind up at Studio 54, which in the 1970s was the most coveted and difficult to access discotheque in New York. Imée and I would enter through a back door (the front was mobbed by dozens, if not hundreds, of desperate people, trying to get in and catch a sight of celebrities). It was with Imée at Studio 54 that I met some of the most iconic music stars of the time, including Elton John, Mick Jagger, John Travolta, Billy Joel and Keith Richards. Imée knew them all and we would always be invited to their table.

There was usually a crowd of onlookers and desperate people trying to get close to the stars and I could feel the pressure that they were under. Whenever they left the table to go to the toilet or to wander around, they would be followed. It was impossible for these people to go to the dancefloor. There was a lot of alcohol and even more drugs (mainly cocaine). We would drive back to Princeton in the early hours of the morning. Mostly, I was asleep in the back seat.

These evenings at Studio 54 and my time with Imée gave me a glimpse of what fame and fortune brought with it, and I didn’t like it. I felt that Imée (and the famous musicians she surrounded herself with) mostly led unhappy lives. They were surrounded by people who were asking for favours or were attracted to them for their fame, not because of who they were. Imée couldn’t lead the life of a normal student, she wasn’t free to move around on her own, she couldn’t eat in the university’s common spaces, and she frequently had obligations to attend to, because she was Marcos’s daughter and her father would ask her to meet this or that person, and convey this or that message. It was difficult for her to even reach her parents, and she had to be careful what she said to people, just in case the wrong message would somehow hit the press. I guess I was lucky because I was not American and she felt that she could trust me. I guess she also sensed that I would not take advantage of my knowledge of who she was.

Imée was a very bright girl, who suffered immensely from her lack of freedom and from the suspicion she had that those surrounding her were not really interested in her, but the power and wealth she represented. This explained her frequent ups and downs. On a good day, she was absolutely breathtaking, witty and incredibly smart. But there were many bad days, when she was irritable and mired by depression. She loved her father and thought that he was very bright. But she hated her mother, her lavish spending and the power she liked to make use of.

Imée and I drifted apart after a while, and she would never graduate from the university. Her inconsistency led to the university losing patience with her, and never awarding her a degree. She returned to the Philippines and continued a life of ups and downs, first marrying a golf and basketball professional, with whom she had three children, then divorcing him, then having several very public, short-lived liaisons. She has been on and off in politics and frequently on the front page of the press because of corruption scandals.

My time with Imée made me understand how lucky I had been not to have been born into a family of notoriety and wealth. Being rich and famous, I realised, could be a curse, and explained why many of these people were so unhappy. It was even worse if, like Imée, you were the son or daughter of very famous individuals. On the surface, people like Imée had everything, but in reality, they were often sad prisoners of an environment in which they were not free.

Many years later I learned about the fraud and depravity of Imée’s father’s government, how opponents were mercilessly persecuted and killed, and how the family stole billions from the Philippines, before being forced to leave the country in 1986. Imée has actively participated in the attempts by the Marcos family to regain power in the Philippines since then. It was through corruption that the Marcos’s could live in such opulence. The lessons I learned during our time together were important to me, but I’m ashamed of my lack of lucidity at the time. With a little thought, I could have reached the conclusion, even without the facts that came out later, that the opulence I was witnessing could only have been possible through corrupt practices, and I would have not spent as much time with Imée as I did.

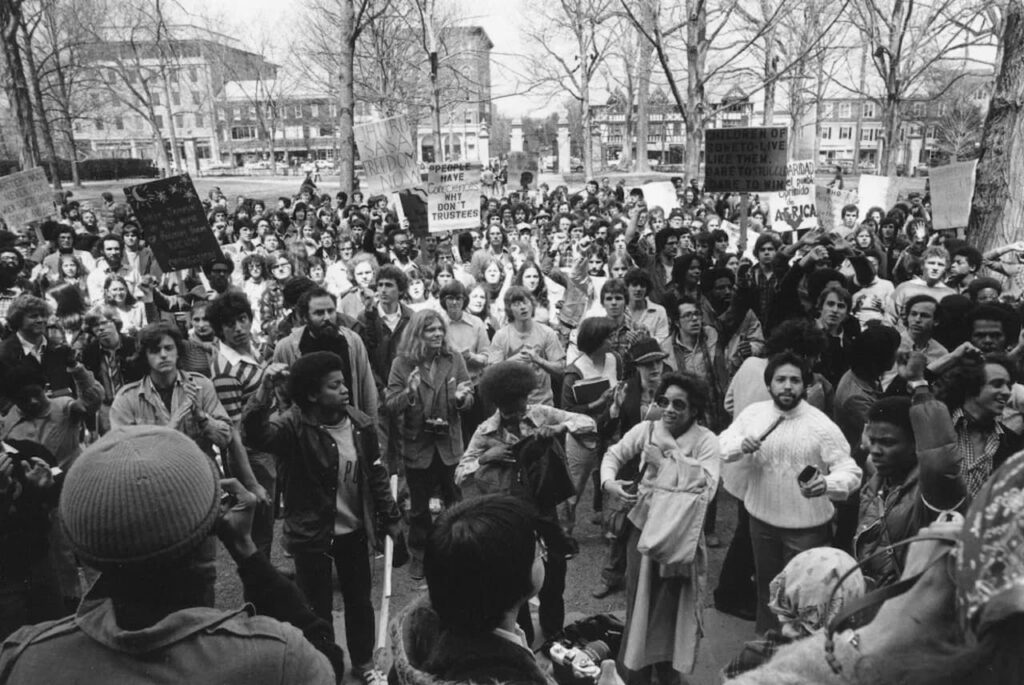

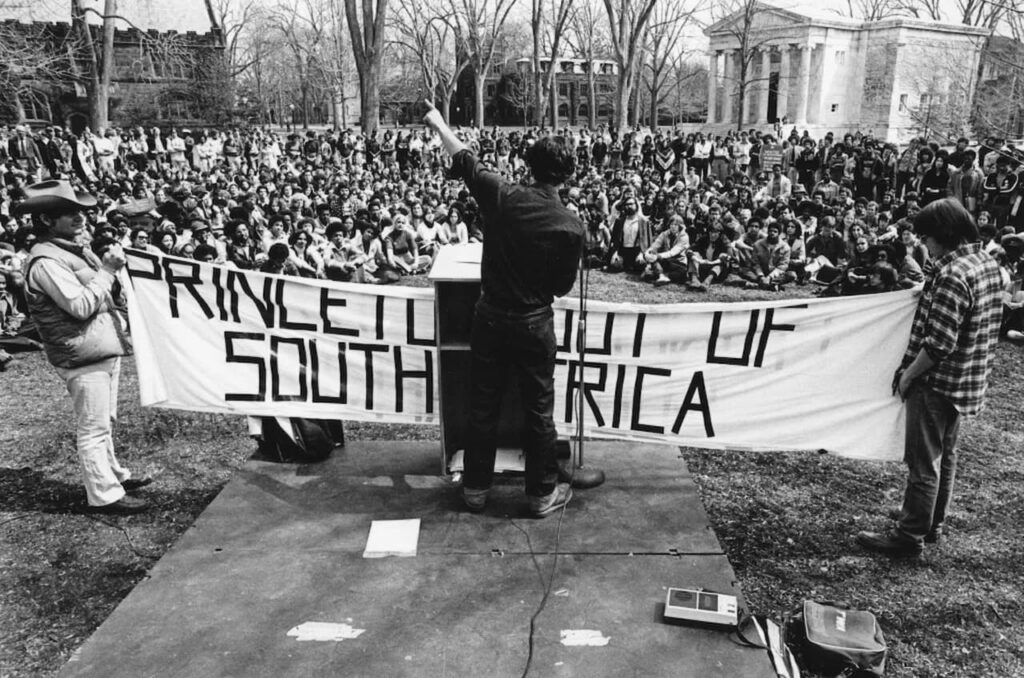

During my years at Princeton, there were not many major political issues that mobilised students. The Vietnam War had finished, as well as the 1973 Arab-Israeli conflict. China was only slowly re-entering the global scene, following the death of Mao, and the cold war between the US and the Soviet Union was in a period of relative calm. But there was one issue that occupied the minds of many students, and that was South Africa, where segregation had been institutionalised through a system called apartheid. Apartheid meant that the black population, who were by far the majority, were relegated to second-class status and had no civic rights. The country was run by a minority white government, who ensured that the white population stayed dominant, not only politically, but also socially and economically.

A movement was started by several US universities, including Princeton, to put pressure on the South African government and the minority white group they represented, by attacking them where it hurt most: their economic privilege. The student movement was aimed at forcing universities to eliminate from their investments any company doing business in South Africa. The largest US universities are private and have very large endowments. The idea of eliminating such investments would not only have a direct effect on the companies in question, punishing them for their investments in a racist country, but would also weaken the power of the local white minority.

I participated actively in the ‘Princeton Out of South Africa’ movement, including a sit-in and brief occupation of Princeton’s historical Nassau Hall in April 1978 (which brought back memories of the El Colegio occupation). I was also part of a large student protest in front of Corwin Hall, at the time when the Board of Trustees was meeting. Both these activities were filmed by film crews, and appeared prominently on US national TV, as well as internationally.

Most US universities, including Princeton, eventually did divest from investments in companies doing business in South Africa, and this contributed heavily to the abolition of apartheid in the early 1990s and the election of Nelson Mandela as President in 1994. The peaceful nature of our movement and the success it had, left a lasting impression on me. Since then, I’m convinced that many of the world’s issues (political, economic or ecological) can be tackled by peaceful citizen action—simply by refraining from investing in companies that do business in areas or for regimes that are detrimental. If we wait for politicians to change the world, it won’t always work. Put under pressure, the private sector can be much more effective in fostering desirable and rapid change.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko