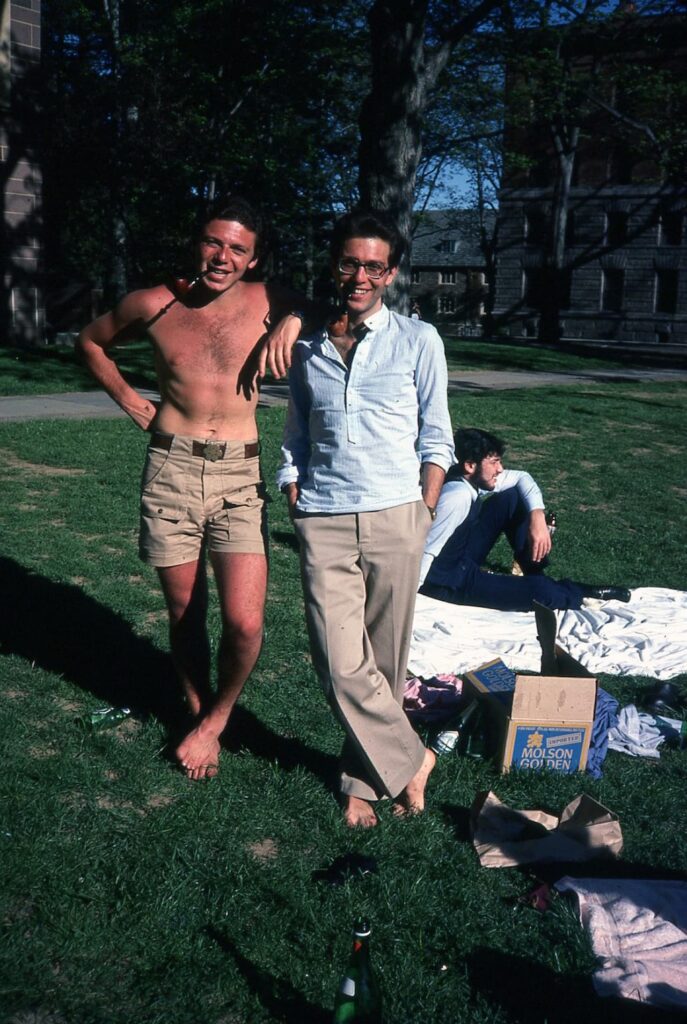

As soon as I arrived at Princeton, I started an active correspondence with Fer, who had returned to Argentina from our year in Europe, and had started to study at the University of Buenos Aires. He was very unhappy. The military government stifled any kind of serious debate or learning. I encouraged him to apply to the US, which he did. He wrote one of the most extraordinary applications that I have ever seen and was accepted with full scholarships to Harvard, Yale and Princeton—an absolutely incredible achievement, which only one person I know has ever repeated. He enrolled at Harvard and for the next three years we saw each other often, in Cambridge or Princeton.

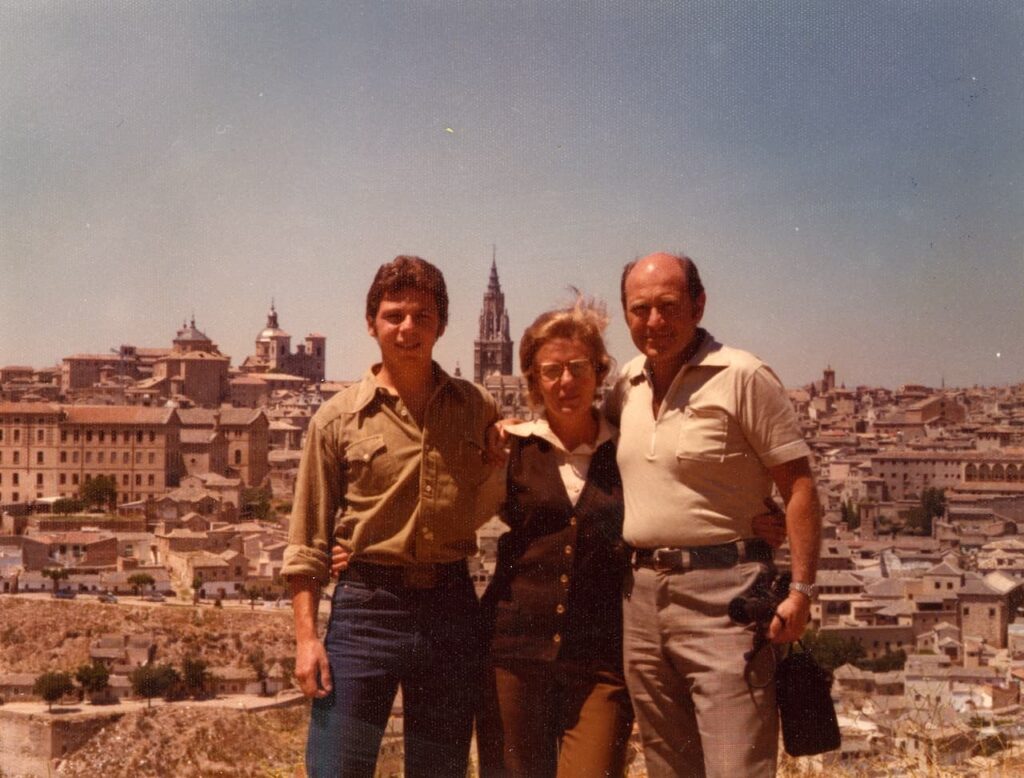

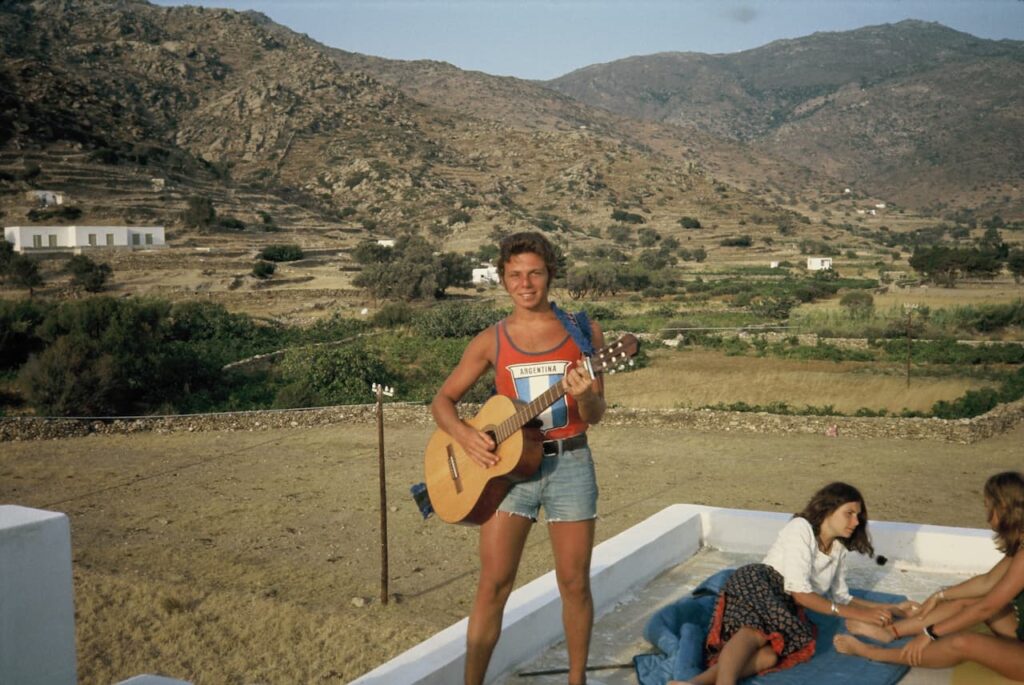

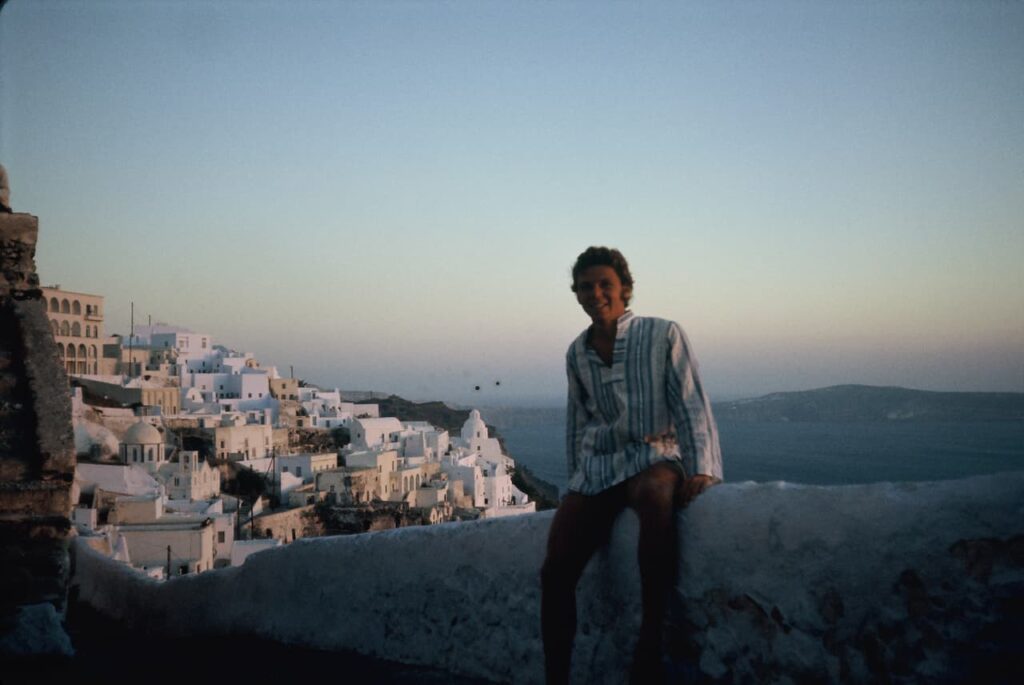

During my Princeton years, the summers were spent traveling. During the summer of 1977, I spent a few days with Paul and Lisl in Spain, not realising that it would be our last holiday together (they would separate the following year). However, the bulk of the summer of 1977 I used to discover the Greek Islands. Or rather, to discover hedonism. It was very much of a rock-and-roll experience. I drifted from one group of people to the next (mostly it was Scandinavians), slept on the beach and spent my afternoons in tavernas. It was also a summer of many liaisons, most of them not lasting more than a day.

It was also during this summer that I saw Kirsten again. We had stayed in touch since our time in Lausanne, and met up for a few days in Greece, where she was vacationing with her sister. We decided then and there to travel together in Denmark the following summer, which we did.

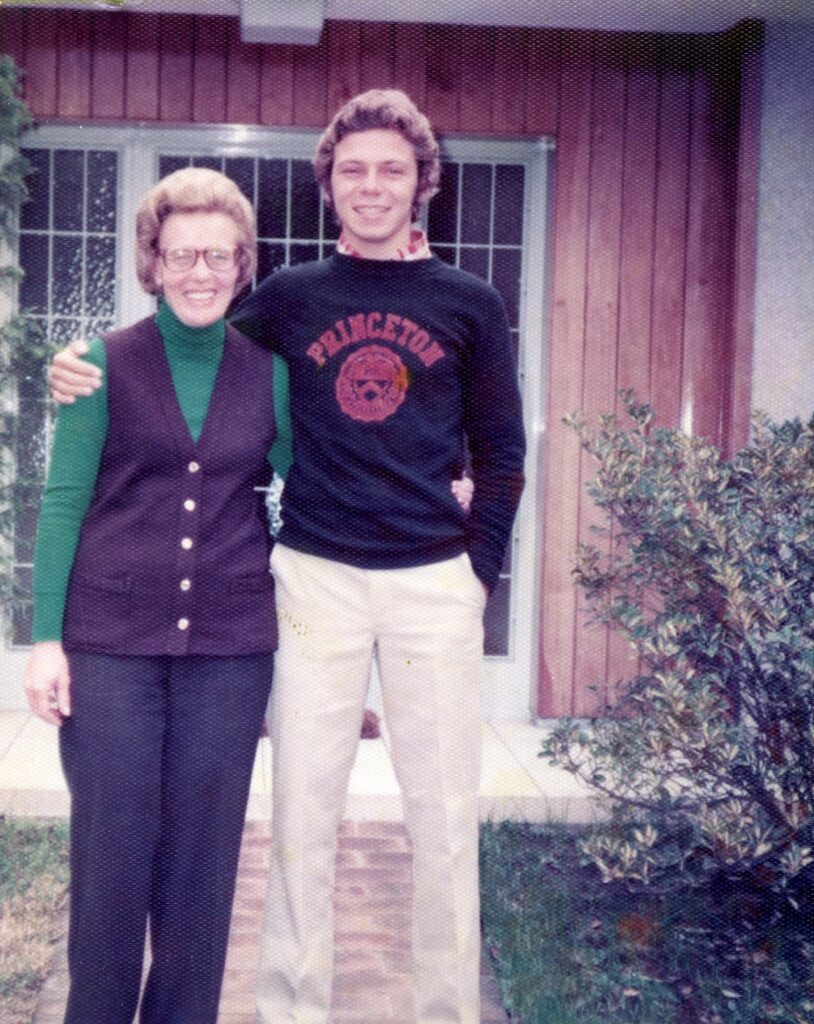

When I landed in Buenos Aires in May 1978 after completing my second year at Princeton, both my father and mother were waiting for me. This was unusual. In the past, whenever I had arrived on a weekday, as was the case now, only my mother was at the airport. My father stayed in the office, called me as soon as I was at home and then joined us for dinner. But this time he was also there. And he was not dressed in business clothes, indicating that he was taking a day off. As soon as we got home, the mystery was lifted: Paul and Lisl told me that they had the intention of separating. ‘What do you mean by intention?’ I asked. ‘Well,’ Paul said, ‘it’s what we want to do, but we are concerned about our children’s reaction, so we’d like to hear what you think of this.’ I said that if they felt that they would be happier living apart, then I was all for it. They both gave a sigh of relief and asked whether I could help them communicate their decision to Edi and Sonia, who were unaware of anything. ‘Of course,’ I said.

Later the same day, Paul and I went for a walk. He explained more in depth what had happened: the years of increasing disconnection between him and Lisl, and her recent love affair with her former psychiatrist, which I had vaguely heard about. Then he told me that he had fallen in love too, with Sylvia Lobstein-Weil, twelve years younger, who I had met. Full of enthusiasm, he told me that he felt again like a 20-year-old, how excited he was to be with Sylvia (who had recently divorced from Stefan Weil, who I also knew), how many things they had in common, etc. Would I like to meet Sylvia? he asked. ‘Of course,’ I said. Another sigh of relief.

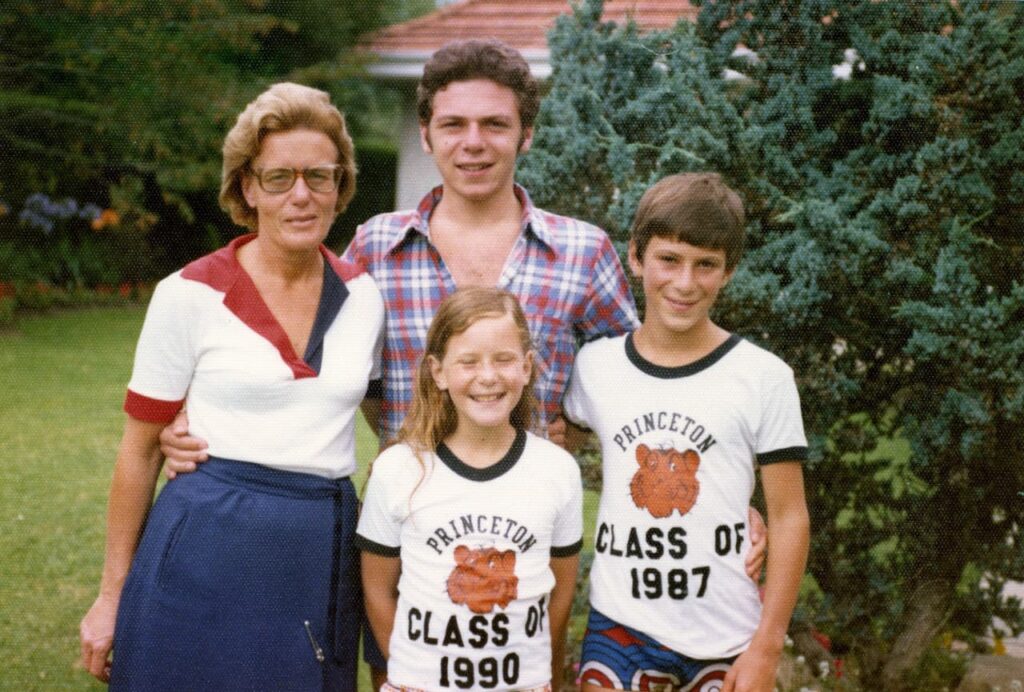

When they heard the news, Edi and Sonia were less than thrilled. Sonia cried a lot, asked why we couldn’t be a ‘normal’ family. Edi kept his disillusionment and unhappiness to himself, but it was clear that what had happened struck him deeply. I tried my best in the weeks that I was in Buenos Aires to be close to them and console them, but it wasn’t an easy time for my siblings. For Edi, it helped that Argentina was hosting the football World Cup. Paul had bought tickets for Edi and I in an indoor facility that transmitted all the matches live on a giant screen. We saw all of Argentina’s games, including the final, in which Argentina for the first time became world champion. We then celebrated for many hours in the centre of town, surrounded by thousands of fans.

During the time I spent in Buenos Aires, I was often at Sylvia’s, where my father was now staying. I reconnected with Carlos and Betty, Sylvia’s children, who were a few years younger than me, whom I had known vaguely. Edi and Sonia were a bit slower in connecting with ‘the Weils’, but over time the impression you gained from seeing us, was not that there had been a divorce, but that the family had grown. There were now five children, and whereas we didn’t all live under the same roof, there was no bad blood between any of us. During the initial months following their separation and later divorce, Lisl offered Sylvia a four-leaf clover accompanied by a note, symbolically ‘transferring’ Paul to her and wishing her much happiness with him. Sylvia has kept the note and the clover in her wallet ever since.

My parents handled their separation and subsequent divorce extremely well. Paul was totally transparent about the family assets, many of which were outside the country and would have been difficult to identify in case their divorce had landed in the courts. He split their assets 50/50, protected my mother from overspending by ensuring that she was left with mostly real estate, but enough cash to ensure a comfortable life. For many years following their divorce, Paul helped Lisl handle the financial assets she received. My father only gradually moved to Sylvia’s home and was present for many years at Lisl’s home for Christmas and all other major celebrations. For the rest of their lives, I never heard either of them say anything negative about the other. They continued to care deeply about each other. Their extraordinary attitude had a big impact on me. When the time of my divorce came, my parents’ attitude stood as a guiding light for me.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko