When spring of my second year at HBS arrived, it was time to think of my career. With no prior business experience, other than the little exposure I had had to banking and my time at Simko in Buenos Aires, I had no idea what I would be good at, or what I would enjoy doing. So, one day, I pulled out all the cases I had taken since starting at HBS—there were almost 500. I placed in a pile all those that I had really enjoyed. They included ‘Dunkin’ Donuts’, ‘Benihana’, ‘Smuckers Ketchup’ and ‘Coca Cola’. I realised that every case was about consumer marketing. I researched which would be the best company in this area and quickly found out that Procter & Gamble (P&G) was the very best address.

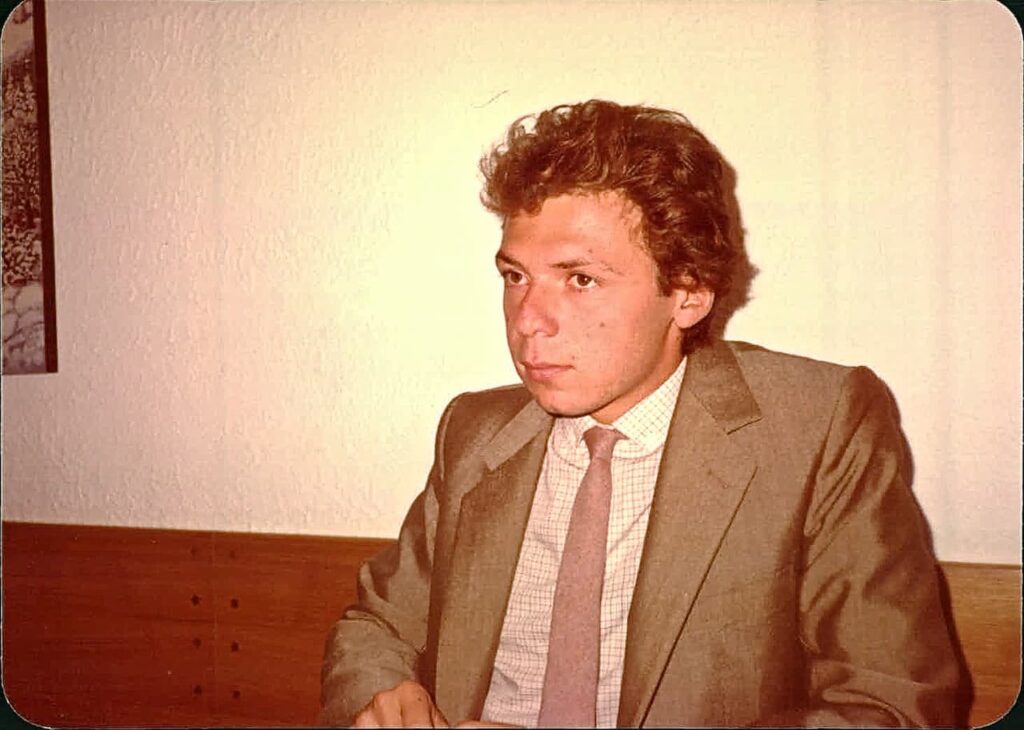

I cut my hair, got myself a jacket and a tie and contacted P&G. From the start, I loved my meetings with P&G—a principled, straightlaced company, that was totally focused on understanding consumers. This was a firm that thought long-term and only hired at the entry level. Their salaries weren’t great, but they nurtured and developed their personnel, and had a competitive, but warm and very friendly culture. They very quickly offered me an entry position in marketing. There was only one negative: Cincinnati, Ohio. I couldn’t imagine living in the Midwest, but eventually acquiesced, thinking that it was a small price to pay in return for getting trained by P&G.

I also applied at Young & Rubicam, at the time one of the world’s best known advertising agencies. For the final interview I was invited to New York, where the meetings started at 9am. I had arrived the evening before, and early in the morning went for what I thought would be a short run, However, I ran in the wrong direction and got lost, arriving at the hotel less than 30 minutes before my interviews started. I had just enough time to shower, change and sprint over to the Y&R office on Madison Avenue. My morning interviews went well, but then lunch came and Y&R had, in good advertising style, booked a table in a fancy restaurant with a large terrace. It was a hot spring day and I was placed on a seat where, gradually, the sun began hitting me. The lunch started at about 1.15pm with, as was customary in the industry at the time, a dry martini. I had had nothing to eat and no water to drink since the evening before and was completely dehydrated after my 90-minute run. We all had a second drink, then wine with the meal and port to accompany cheese. I was very slow walking back to the office for my afternoon meetings.

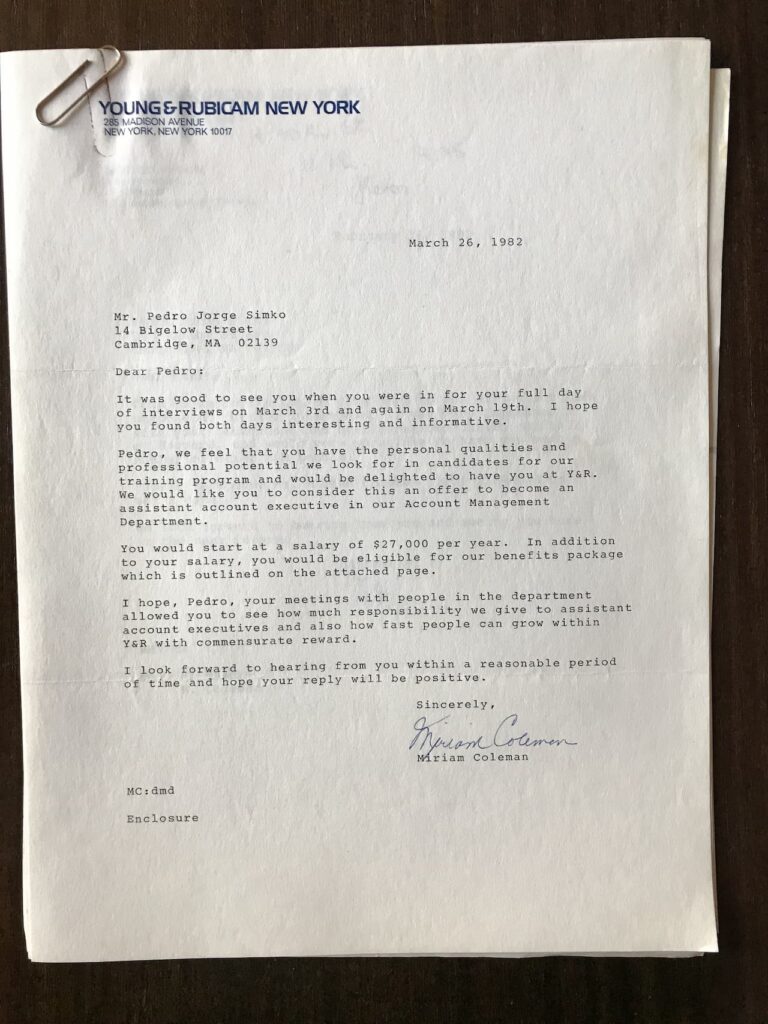

A few days after my interview, I received a call from Y&R. It was the Head of Personnel. She said that they faced quite a paradox with my application—my morning interviews were brilliant, but the afternoon ones were nothing short of dismal, and that they thought that the lunch may have played a role. Would I care to come back and interview once more? ‘Yes,’ I said, greatly relieved. This time, I made sure that I was well fed and properly hydrated for my meetings. I received an offer, which I declined in favour of P&G. It was my first, but by no means my last encounter with the advertising industry.

A few weeks after accepting their offer, I received a call from P&G in Cincinnati. They had looked at my background once more, realised that I spoke a few ‘foreign’ languages and thought that perhaps I might be interested in starting with P&G at their Swiss office, located in Geneva. Would I care to go and have a look? They couldn’t guarantee anything, since Geneva had their own hiring practices, but they would be happy to facilitate an interview. I said yes, with pleasure.

A few days later, my plane ticket arrived. It was for Rochester, New York. I called P&G and asked why I was being sent to Rochester. ‘Oh,’ said the assistant who booked the flights, ‘I was told that you needed to go to Geneva. I looked it up on the map and the nearest airport is Rochester. We could also fly you to Ithaca, if you prefer; both these airports are about two and a half hours from where you need to be.’ I was being sent to Geneva, New York.

This incident said a lot about P&G at the time—it was an almost exclusively US-based company, where anything outside the US was unfamiliar, even to the people in charge of booking flights. This was about to change, and I arrived at exactly the time when P&G’s top management had their sights set on transforming the company into a true multinational. But clearly, the message had not yet arrived at the lower echelons.

After the confusion about my plane ticket was sorted out, I landed in Geneva, Switzerland on a morning in mid-April, 1982. I left my luggage at the hotel and went to the GATT office (now OMC), where I had an appointment with a Harvard professor who was spending a year there on a consulting project. It was a bright, sunny day and the professor had an office on the top floor, overlooking the lake. He warmly welcomed me and started to tell me about his research. He had a large office, including an area with two sofas and a coffee table, but he seated facing his desk and the window. ‘Would you mind if we change seats?’ I said after a while. ‘Is something the matter with your chair?’ he asked. ‘Oh no,’ I said, ‘it’s just that I can’t concentrate—instead of listening to you, I find myself looking out of the window at the lake and the white mountains in the distance!’ The rest of the conversation was held on the couch, but I still had trouble concentrating, my mind kept drifting back to the magnificent view from the professor’s window.

After my time with the professor, I walked back to the town by the lakefront. By the time I arrived at the Noga Hilton Hotel (now the Kempinski), I said to myself that if P&G offered me a job in Geneva, I would take it, no matter what the job was about or the financial conditions. And that I would spend the rest of my life in this town. It’s exactly what I did! My coup de foudre for Geneva has never waned. To this day, whenever I return to Geneva, I feel the same deep love for this town. The passage of time has changed nothing in my passion. It may have even increased over time. On that spring afternoon in 1982, I had found my home.

Through an extraordinary coincidence, Jorge Luis Borges also thought of Geneva as his home. A few years after I settled in Geneva, he would return to die in the city where he had lived as an adolescent and where he felt that he had spent his most auspicious years. This is what he had to say about Geneva:

Of all the cities on the planet, of the diverse and intimate homelands that a man seeks and deserves in the course of travel, Geneva seems to me the most conducive to happiness. Unlike other cities, Geneva is not emphatic. Paris is not unaware that it is Paris, decorous London knows that it is London, Geneva hardly knows that it is Geneva. The great shadows of Calvin, Rousseau, Amiel and Ferdinand Hodler are here, but no one reminds the traveler about them. Like Japan, Geneva has been renovated without losing its yesterdays. The mountainous alleys of the Vieille Ville remain, the bells and fountains remain, but there is also another great city of western and eastern libraries and shops. I know that I will always return to Geneva, perhaps after the death of the body.

With my professional future now clear, I had no patience to stay longer than I needed to in Boston. As soon as I finished my last exam in the middle of May, I took my savings out of the bank, closed my account and boarded a flight to Athens. To the disappointment of my parents (especially Paul), I did not stay for graduation. I much preferred to explore Greece than wait for another three weeks to receive a diploma. It took two decades before I received my diploma, which arrived in the post one day with a message from the university saying that since I had never claimed it, they were shipping it to me. The note included a belated congratulatory message.

Before leaving the US, I stayed for a few days in New York and started a diary. The first entry is from Greenwich Village and it is dated May 20, 1982, the afternoon before my flight left. In it, I reflect on my time in the US and I conclude that there was very little that I was leaving behind. During my six years in the US, from the age of 19 to 25, arguably the most important in a person’s development, I did not succeed in establishing an emotional relationship with this nation. Yes, there were friendships, like the one with Eric, that meant a lot to me and which I would cherish and keep forever. But the US lifestyle was not for me. The focus on quantity vs. quality, the relentless materialism, the superficiality and lack of sincerity in most interpersonal relationships, and the general absence of deep and happy family connections, made me feel like a stranger in this otherwise friendly and welcoming country, which didn’t yet feature the tension and antagonism of the Trump years.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko