Harvard Business School was a shock for me. While at Princeton, I had been surrounded by hugely interesting, smart and multifaceted people, who rarely took themselves seriously and who, for the most part, believed in a balanced lifestyle. The HBS I witnessed in the autumn of 1980 was filled with hard-nosed individuals, whose only interest appeared to be to make money, lots of it, at any cost, with little or no interest in what contribution they were making to society. Nearly all the students were two or more years older than me. Few had any interests or wished to talk about anything else but how best to get rich fast.

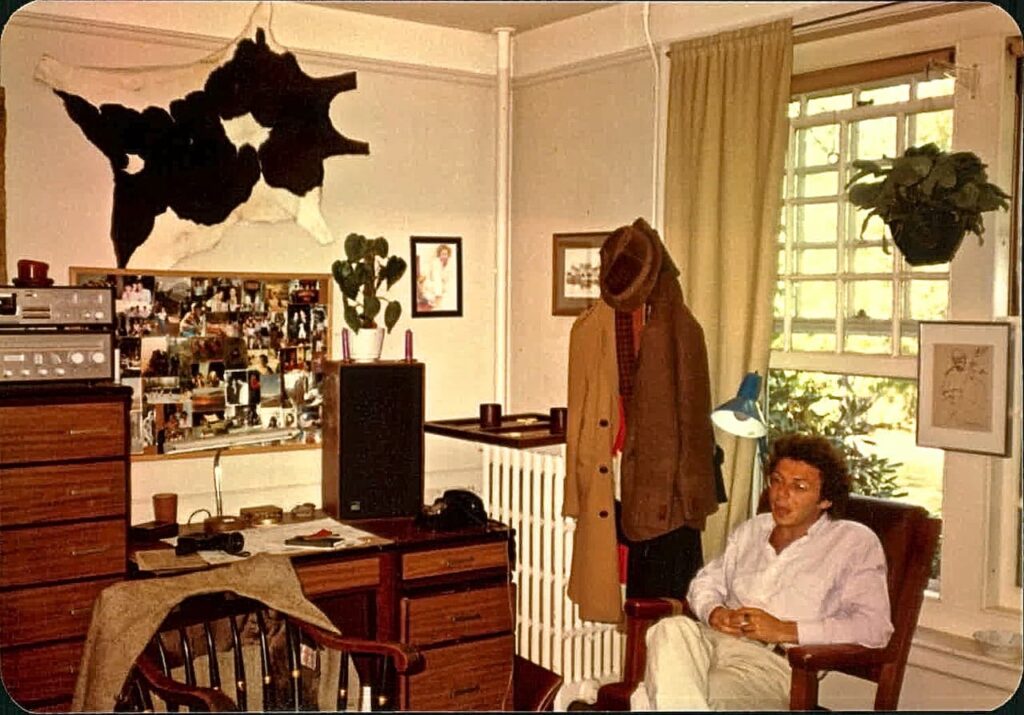

While most men wore short hair and went to class wearing a blazer and button-downed white shirts, I showed up to with long hair and wearing wooden clogs, accompanied by sleeveless or brightly coloured shirts. On weekends, I often went to discos in Boston with lips painted in bright red and a feather earring.

What made my first year bearable at HBS were Sally and the Boston Marathon. Sally was from California and, like me, one of the few HBS students who were admitted directly from college. We hit it off instantly and spent together most of our time outside class. The roommate I had been assigned to (a Cuban-American, who I disliked intensely) moved out in the first weeks (he couldn’t stand the idea of having a roommate), and Sally moved in with me.

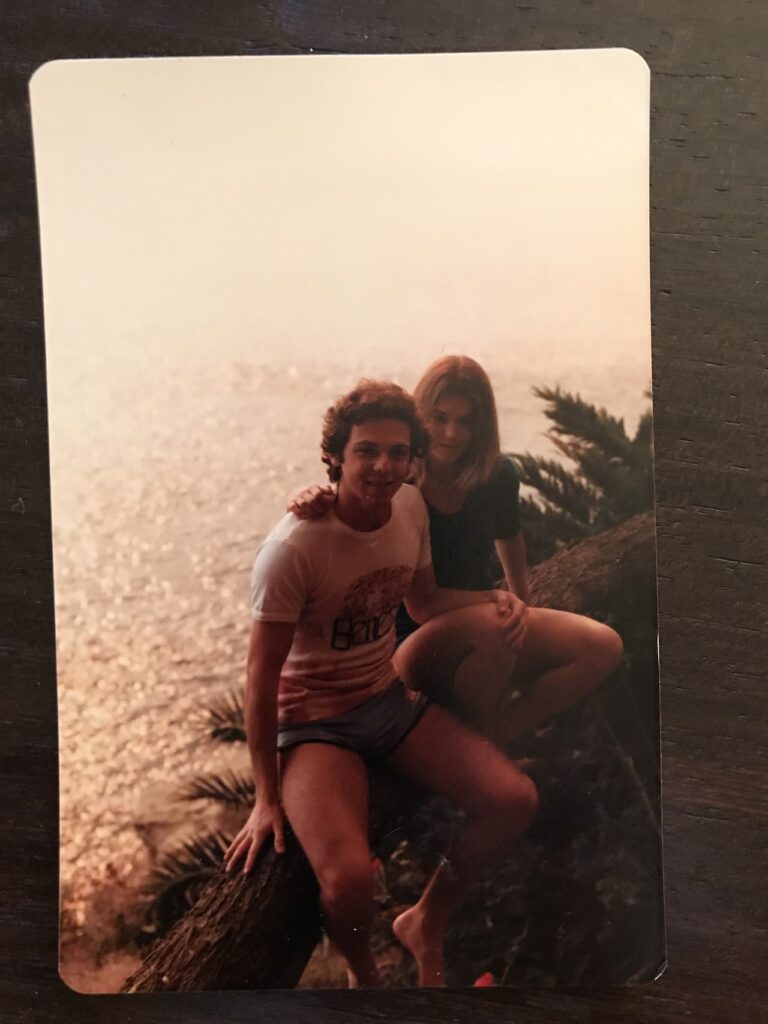

I connected really well with her and, during breaks, went to visit her in her home. Her family lived in South Laguna Beach, in a house that you only really see in films. Descending from a hill, it featured a dozen or more rooms, each one with a perfect view of the sunset on the Pacific. At the bottom there was a private beach, at the end of which were a few large rocks. These rocks prevented the neighbours from peeking in, but were also perfect natural trampolines from which to dive into the water. Wandering around, I found them to be filled with mussels.

I was really excited to find fresh mussels and asked Sally’s mother what recipe she usually used to cook them. ‘Oh no,’ she said, ‘we don’t eat that stuff.’ ‘You mean, you don’t eat mussels?’ I said. ‘We do sometimes eat mussels, but it’s dangerous to take them from those rocks, we’ve been told that they’re poisonous.’ ‘What makes you think that they’re poisonous?’ I asked. We wound up calling the hospital, where we were told that during two months of the year, all mussels were poisonous and should not be consumed. They were safe to eat during the month that I was there. So, I went down to the beach and got a bucketful of large mussels. Back in the kitchen, I found nothing to cook them with. There was no garlic, no parsley, no oil and no bread. In fact, the Upjohn’s fridge, other than a few frozen pizzas, and two or three bottles of milk, had absolutely nothing in it.

I went to the supermarket and bought all I needed. Under the sceptical eyes of Sally’s mother, I then prepared what was to become the Upjohn’s first home-cooked meal since they had moved into this house, about five years earlier. All their pots and pans were brand new, but they had never operated the stove. All of their meals were take-out, or just eaten at the many fast food places found around their home.

When I asked for what time I should prepare the meal, Sally’s mother stared at me with a blank face. ‘We don’t have meal times here,’ she said. ‘What do you mean?’ I asked. ‘Well, people just come and go. They buy their stuff and consume it at their leisure.’ I was puzzled, but Sally said that I should aim for 7pm and indeed a few of Sally’s siblings and her mother were there at this time. But I couldn’t get everyone to sit around the table at the same time. And I don’t think that mussels meunière was anything that the Upjohn’s had ever tasted. So, in the end, I had several large helpings of my mussels, accompanied by large pieces of French baguette. Sally accompanied me, and her mother politely had one or two mussels, all the while looking at us, ready to pick up the smallest sign of food poisoning to rush us to the hospital. But nothing happened. It was a delicious meal. I was later told that from that day on, Sally’s mother decided that It might be a good idea to cook at home every now and again. And, why not, ‘mussels à la Pedro’, but only for guests.

Sally’s family was my first exposure to the American lifestyle. It made me reflect on how fortunate I had been to have grown up in a family where people got together for meals several times every day, where home cooking was celebrated, where bedtime stories were told and where just being together was something people valued. What sense does it make, I thought, to live in such a beautiful house, if you don’t connect with the others? Sally and I broke up in the spring of 1981. We had been together for about six months. At the time, I was heartbroken, but I wonder if our relationship would have had any real future. We really came from very different worlds.

The HBS coursework was very heavy, but I didn’t have much trouble following it. There were no textbooks, all of the learning happened through the study of three cases per day. According to the university’s guidelines, each case took about three hours of study and analysis. After a while, however, I realised that it didn’t make sense to study each case in depth. What was important was to find out what the key learning point was for each one, and to focus only on this. So, one hour of work per case proved to be sufficient for me, and I succeeded in having my evenings free, as had been the case during my Princeton years.

During the obligatory 12 first-year HBS courses, there was only one that had anything to do with people. It carried the ambiguous title of ‘Organizational Behaviour’, and was considered ‘a filler’ and ‘soft stuff’ by my fellow students. The message from the HBS faculty was clear: if you want to make it to the top of the business ladder, what you need are great analytical, strategic and (especially) financial skills; an understanding of people, what makes them tick and how best to inspire them, didn’t matter. No wonder that over two-thirds of the graduating class at the time I was there, went into consulting and investment banking. Very few became what HBS said it aspired their students to be: industry leaders, running large companies and contributing to a better world. HBS has changed over time, and some of the regular conversations I had with the Dean in the late 1990s may have helped (I told him at the time that nothing in the HBS curriculum had prepared me for running my ad agency. I reminded him that 80% of gross national product in industrialised countries comes from the service industry, and that you cannot possibly be successful in services if you don’t understand or cater to the needs of the people in your organisation).

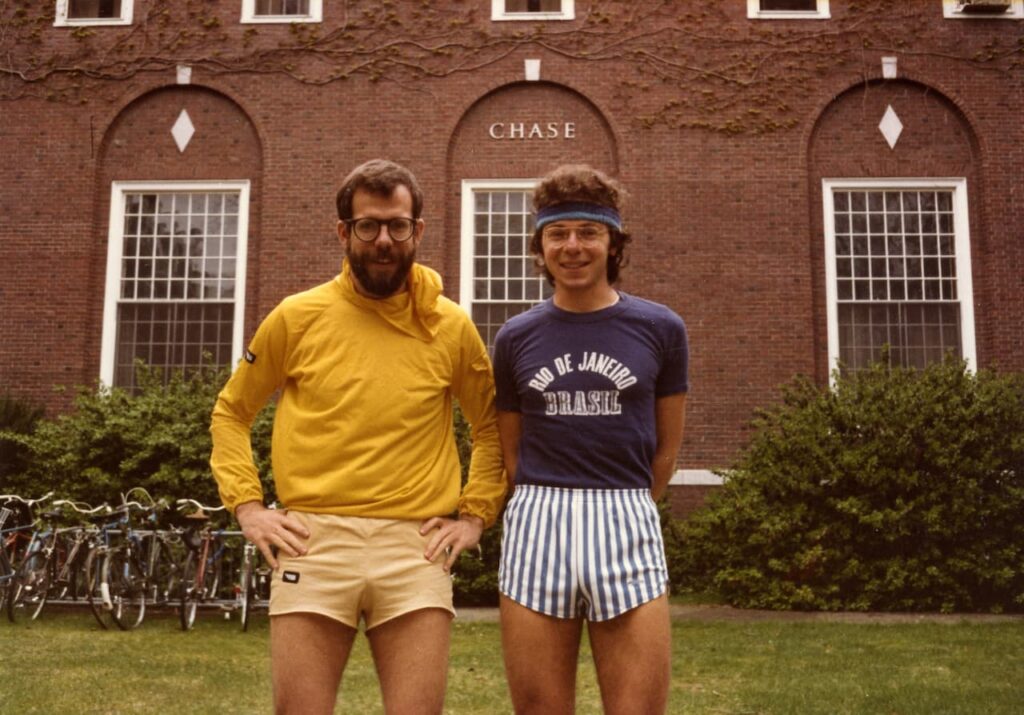

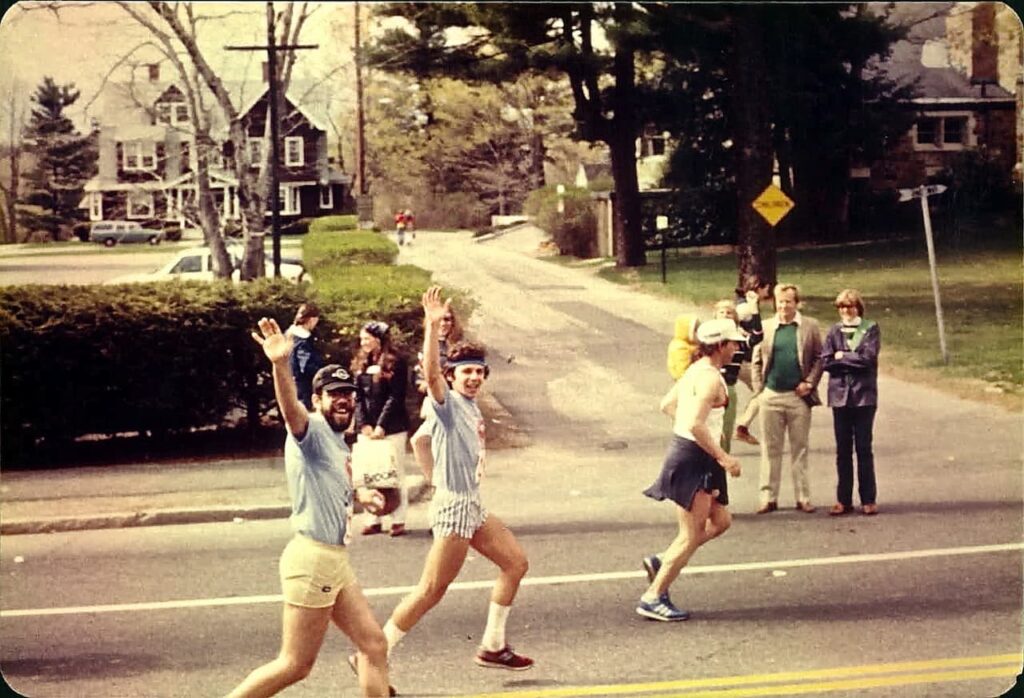

What greatly helped me maintain a very happy study-life balance during my first year at HBS was my preparation for the Boston Marathon. A few days after I arrived, I hooked up with Ed Nelson, a section-mate who was also a runner. We decided to train together for the April 1981 marathon. Already at that time, the Boston Marathon was one of the world’s most prestigious. It was impossible to qualify for it, but in 1981 you could show up on the day and run behind the qualified runners. This was called ‘back of the pack’ and that’s where Ed and I ran.

Training for the marathon provided for daily exercise and a long-term objective. It regulated my appetite and quietened my mind. Ed and I ran every day at 2.30pm, immediately after our classes finished. We followed a training program which was given to us by the HBS Runner’s Club. It involved running by the river Charles, with distances ranging from 5 to 25 km.

Running the marathon was an event I’ll never forget. Ed and I ran side by side, slower than what we would have been able to, finishing in 3h54min.

The consequence was that there was no time during the run when we were not in great shape, completely relaxed, cheering and saluting the crowd. The run is in a straight line from Hopkington to the very centre of Boston. It’s a delightful trip, of which we enjoyed every minute. I felt great at the end, and after a few days was running again regularly.

I ran the Boston Marathon again the following year, but it wasn’t the same. Without Ed, who had decided that one marathon was enough for him, my training was less continuous. It was fun to run with a group of friends, including Eric, who came up from New York, but I made the big mistake of wanting to run faster. I finished the 1982 marathon in 3h25min, but the faster pace came at a steep price—I ‘hit the wall’ a few km before the arrival line and finished totally exhausted. It took me months to recover. I never ran a full marathon again.

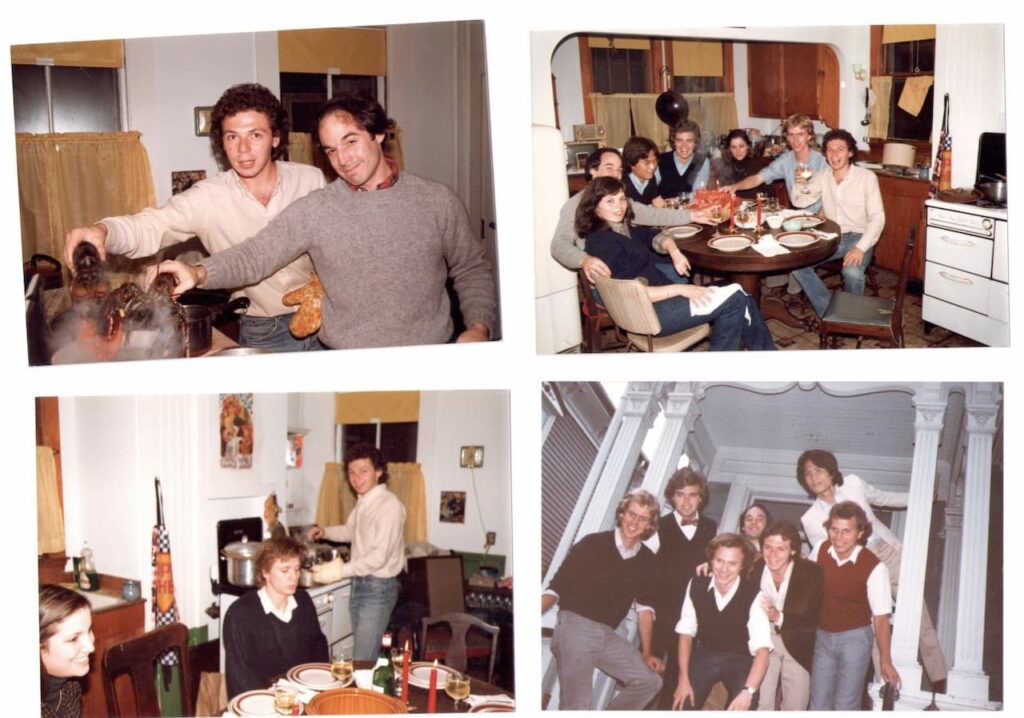

My second year at HBS was much more fun, in large part because I lived off campus with five Norwegians, one Chinese and one American. We were students, at HBS, MIT and Harvard Law School, and together rented a house on 14, Bigelow Street, a place we quickly baptised as ‘The Bigelow Club’.

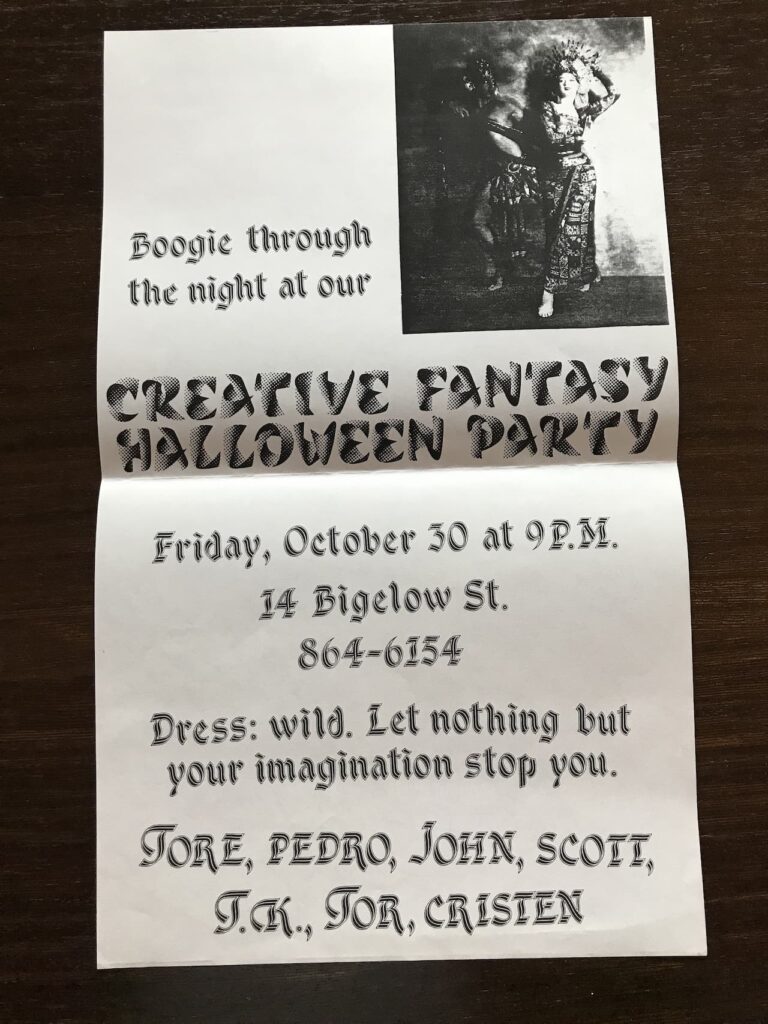

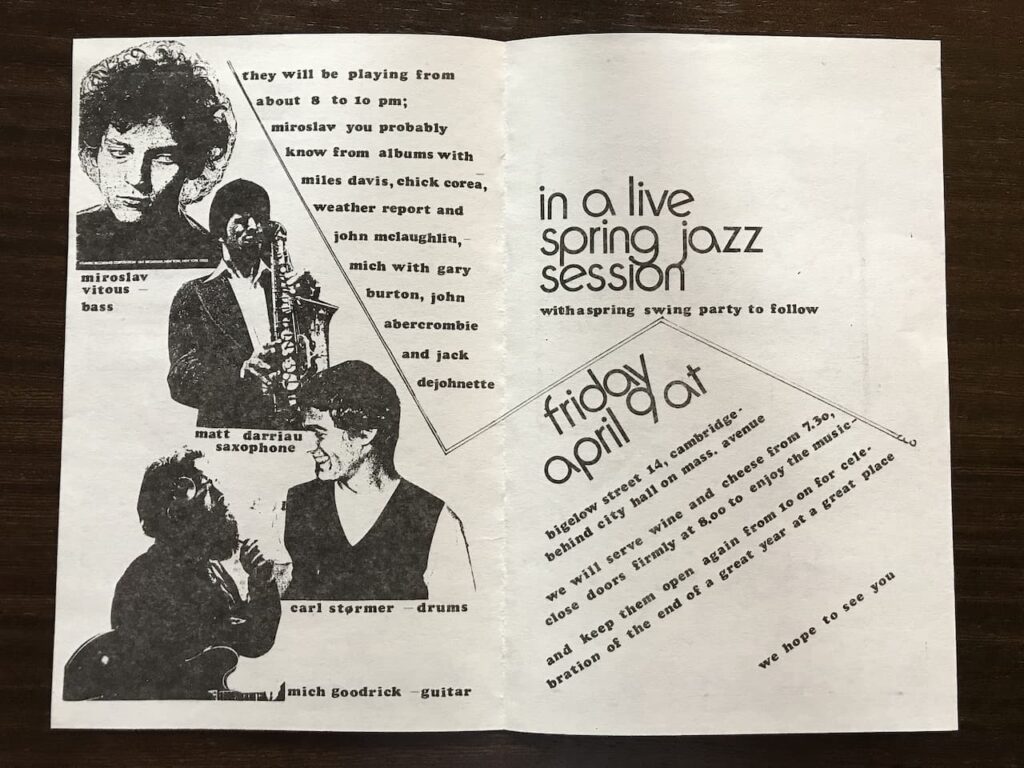

Initially the Bigelow Parties, as they got to be known, took place on Saturdays. After a while, there were parties on Wednesdays and Saturdays. Towards December, parties took place on Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays. By March, there were parties every night, except for Mondays. By end of May, we had no more days without parties.

My roommate Christen, a Norwegian who became a close friend, and I would design the invitations, some of which were quite creative. Sometimes we invited live bands. Before parties, in the afternoon, we would organise lobster races in the kitchen or barbecues in the back yard. We even bought a car, for which we each chipped in $10. The large red Chevrolet Monte Carlo from 1970 died after running for less than one km. It’s probably still parked where we left it, on one of the side streets near the Bigelow Club.

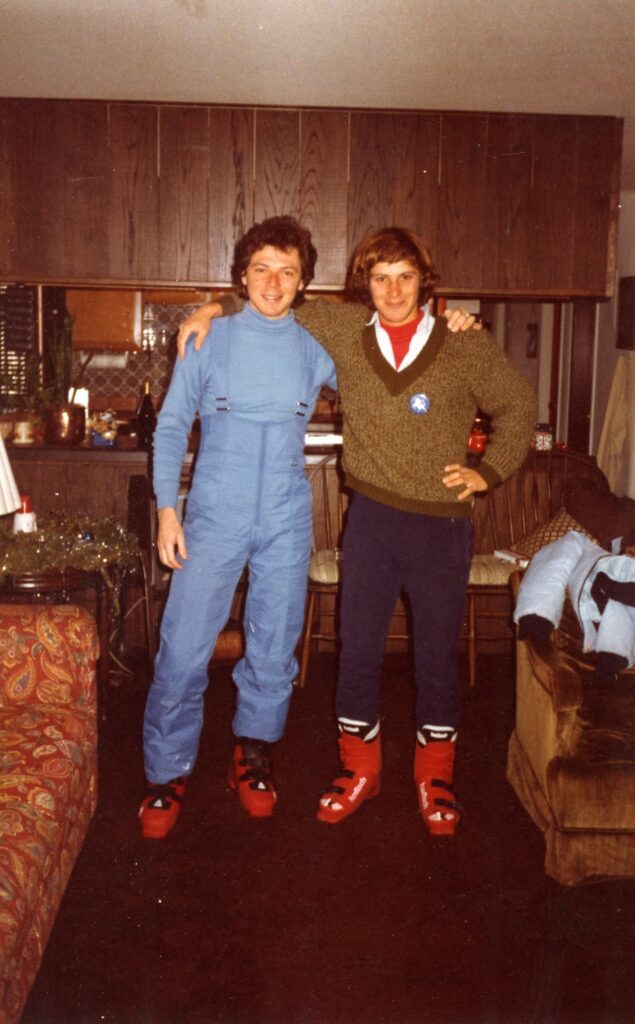

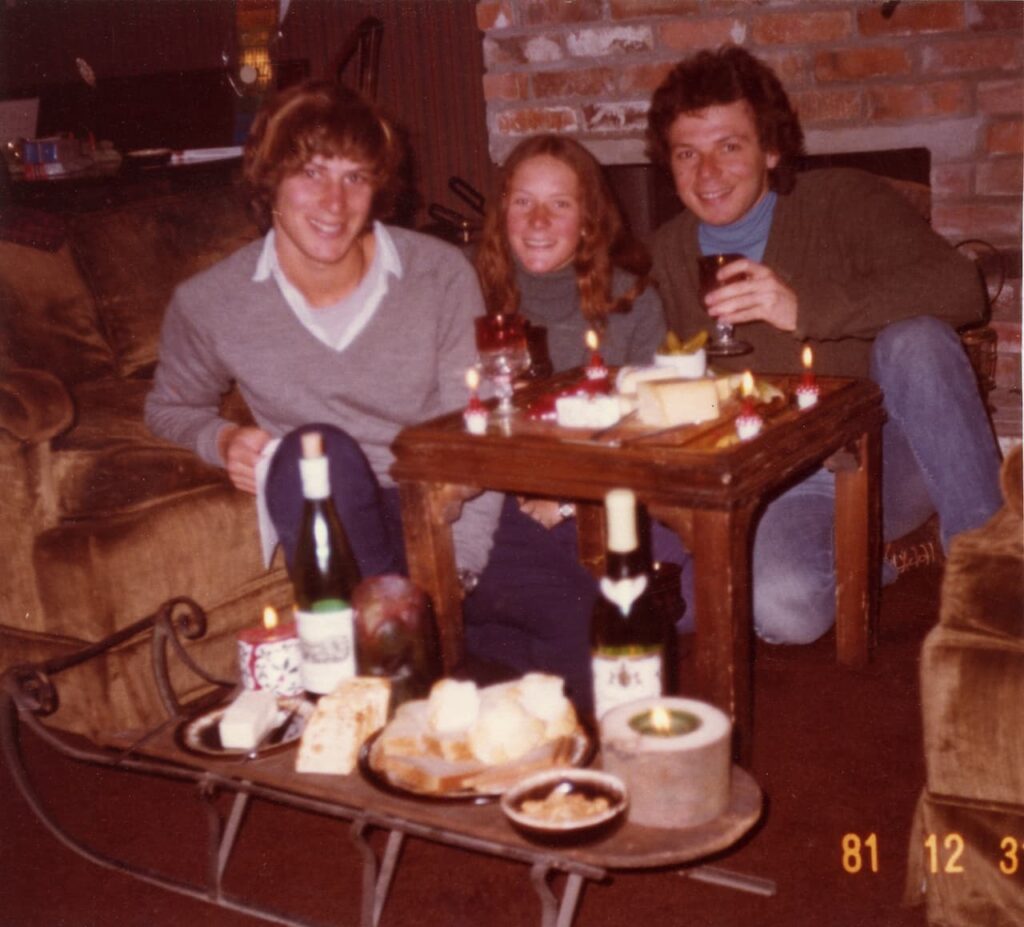

For Christmas and New Year of 1981, Lisl, Edi and Sonia came to the US and we rented a chalet in Aspen. I had only recently learned how to ski and was very clumsy. Edi and Sonia were much better at it. In the evenings we would have gargantuan meals (mostly fondues). It was my first exposure to Christmas in a mountain chalet and I loved it.

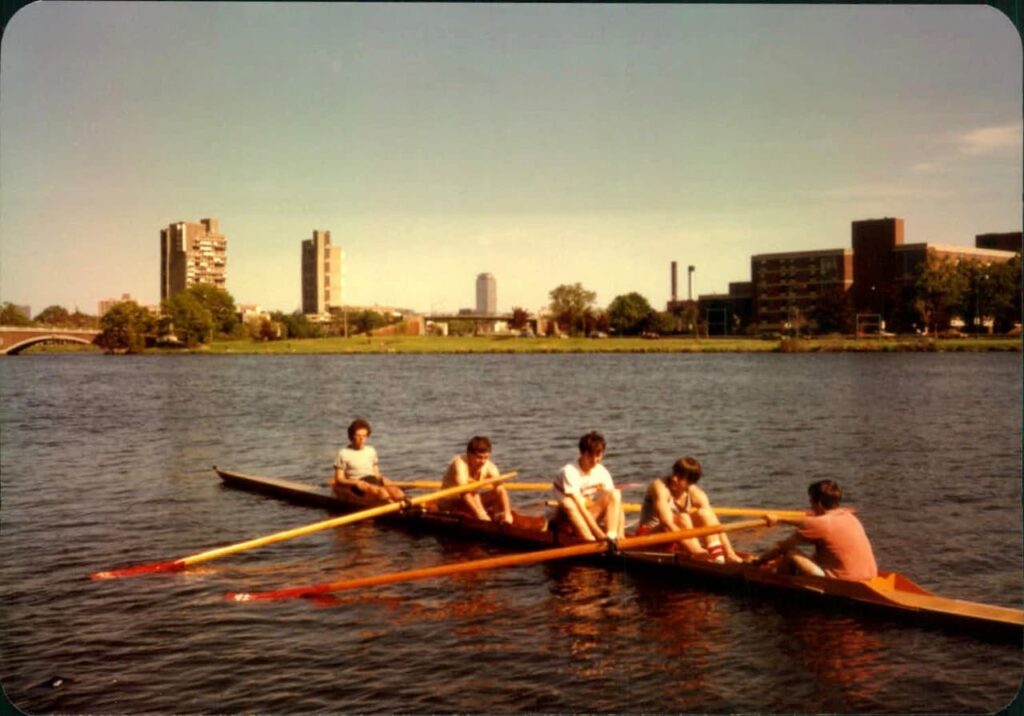

My second year at HBS left time for an additional sport, so I joined the HBS Rowing Club. The whole experience was a bit of a joke, with the crimson oars featuring a large dollar sign, but I loved to be out on the water in the early hours of the morning.

During my two years at HBS, I saw Eric quite often. We would meet in New York, where he was a medical student at Columbia or, more often, at his grandfather’s ‘farm’. I put farm in quotation marks because that’s what it was called, but I never saw any farming happen there. The weekends were all about drinking and playing board games, especially backgammon. The day would usually start with omelettes, into which a bit of beer would be mixed (you know, to give them a fluffy taste, Eric would say). Because only a small amount of beer was needed for the egg mixture, but we never thought of wasting the rest, beer drinking started early in the morning, amid wild cheers and Eric’s M-ectomies (he would buy bottles of Molson beer, from which he would diligently and carefully scratch out the M, proud to drink his own beer).

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko