Princeton afforded me the opportunity to try my luck on a few business ventures. During my freshman year, I sold beer mugs to my fellow students, with sufficient success to earn me close to $1,000— a lot of money for me at the time. But in my Junior year, I developed a venture that turned out to be even more lucrative.

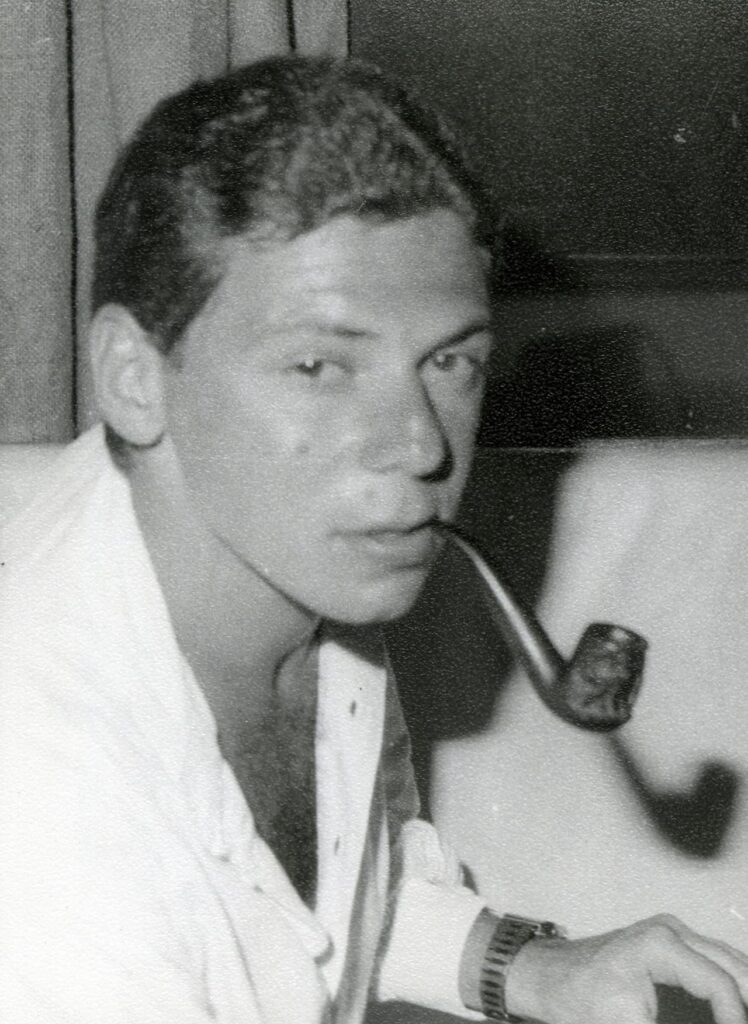

I had begun to smoke a pipe during my second year at Princeton. The same way as nowadays I’m fascinated by tea, because I like the immense variety, the subtlety of different forms of preparation, and the beauty of different teapots, I got intrigued by pipes and pipe tobacco at the age of 20. Soon, I had collected half a dozen pipes and as many books. I learned all about the different materials used to manufacture pipes and the history of pipe smoking throughout the ages.

After a while, I founded The Briar and Clay Society. It soon had two dozen members. The activities involved extensive wining and dining always in beautiful settings, picnics, and the odd lecture on the smoking habits of native Americans or the favourite tobacco flavours sold in Parisian XIXth century bordellos.

Through my contacts in the Princeton community, I had gotten to know a pipe manufacturer. One day, I asked him whether he could carve a special pipe for me, including the letter P (for Princeton) and the number 80 (my year of graduation). He did, and the result was great. Wherever I went, I would take my ‘Princeton’ pipe. One day, during a reception, an elderly lady came to me and asked where I had gotten this pipe. I told her and she asked whether I could facilitate her getting one for her husband, who was a Princeton graduate, Class of 1955.

From then on, I started to sell ‘Princeton pipes, of the finest briar, including your year of graduation, carved by hand by a local artisan, the ideal present for Christmas or a birthday’. With the help of the Alumni Office, who transmitted names and addresses to me, I started to write to the wives of alumni. I chose the older group, alumni who were 50+. Since I knew each alum’s birth date, as well as the name of his spouse, I wrote personalised letters, which arrived about two months before the alum’s birthday, suggesting that a personalised pipe might be a very original present for her husband. In October of 1978 I hired a secretary and with her help, sent out about 300 personalised letters, inviting spouses to offer their husbands ‘a most memorable present, one he will never forget’.

The business took off like a rocket and a few months before leaving Princeton, I had already sold more than 150 pipes. Interesting was the fact that many of the ladies who bought pipes indicated that their husbands did not smoke, but that the pipe ‘looked great’ on their husband’s desk.

It was a lucrative business. I paid $15 for each pipe, and sold it for $85. Before leaving the campus, I sold the business to a sophomore for $ 4,000. All in all, I made close to $15,000 from this venture, a huge amount for me at the time. I have no idea what happened to The Briar and Clay Society or the pipe business after I graduated from Princeton, but this early entrepreneurial experience gave me confidence to try out other ventures in the future.

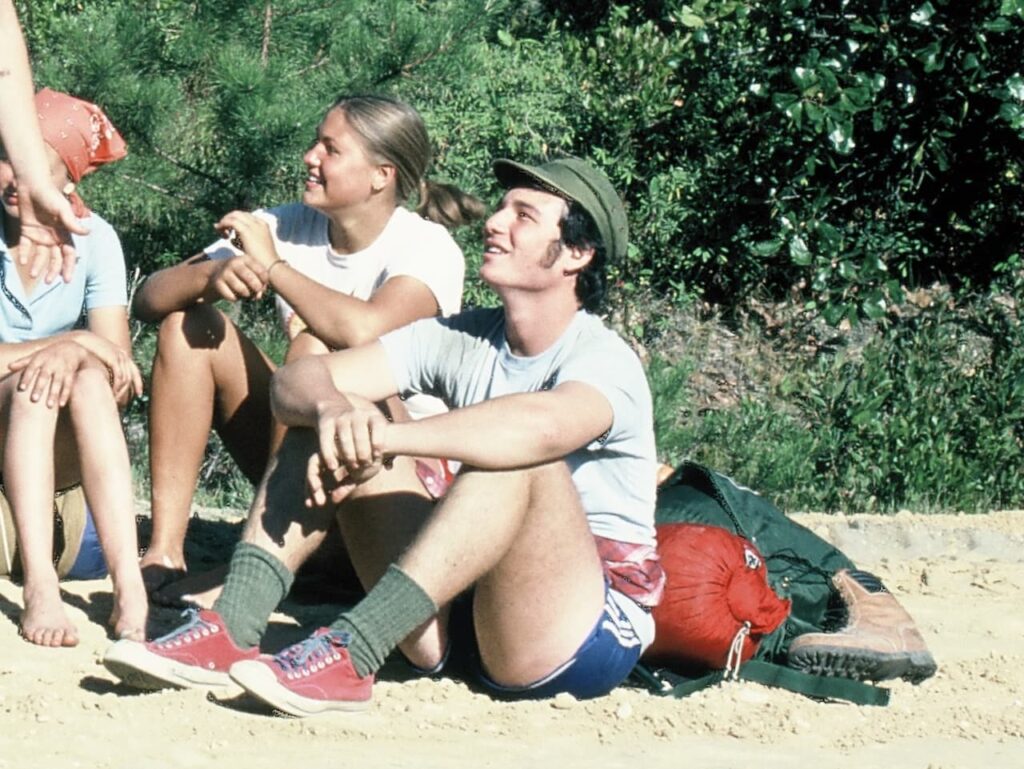

Princeton provided a fertile ground for lasting friendships. One of my soul mates was Bernardo, who I met at the very outset, and who was my roommate for the remainder of my college years. Bernardo had been raised in Puerto Rico, but his family was from Buenos Aires, so we hit it off immediately. Bernardo was really bright, very sociable, totally relaxed and ready for a party at any time of the day or night. His working schedule was the inverse of mine: he left everything to the last minute, appeared totally disorganised, but at the last minute, before an exam or a paper was due, he would pull one or more all-nighters and get his stuff done, with uniformly excellent results. Then he would start the cycle again. I was totally impressed by this master of procrastination’s success, but still incorporated nothing into my Germanic-style work ethic.

Bernardo introduced me to marijuana, but it did not strike a lasting chord with me. I would get high very quickly, after only a few puffs, say a few silly things, wander off to Wah-Wah (the local grocery shop), buy a big bag of chocolate-chip cookies, sit in a corner and eat them all, then go to sleep. After doing this a few times, I concluded that marijuana was not right for me—I preferred to spend my evenings a little more awake!

My experience with cocaine, which also happened during my college years, was very different. My other roommate Bailey invited me to visit one of his friends in Vermont, who had a farm there. It turned out that this friend was also a dealer. When we arrived, there was a large block of pure cocaine on the kitchen table. We sat around the table and Bailey’s friend started to produce lines of coke on small mirrors. I snorted once, then after a few hours again, then again, until it was 4am. I realised then that I could have continued forever.

Then as now, after 10pm, my body begins to send strong signals to go to sleep, but here I was, long past midnight, totally awake and thinking of nothing more than more cocaine. Not only this, but I had no appetite, despite the fact that we had had nothing to eat since the previous day at lunch. And: I felt that every conversation with Bailey and the dealer was the most interesting interchange I had ever had, and every object in the dealer’s small room merited a very attentive study. The next morning (it was already afternoon), when I woke up, I decided that cocaine was far too dangerous and addictive for me, and never tried the drug again.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko