So, in early October, less than two weeks after my failed trip to Cambridge, I was on a flight back to Argentina. In my luggage were the two big books that had been given to me at the US Consulate. My heart was full of enthusiasm to study in the US.

My friends from El Colegio came to receive me at the airport and I was glad to see them, but my mind was elsewhere. It quickly became obvious that the year in Europe had changed me in fundamental ways. I had had experiences that they couldn’t understand. My prospects to study abroad also created a distance that, I sensed, would be difficult to bridge.

So, for the initial months after my return, I was mostly on my own. In the morning, I studied for the SAT exam (my father had obtained additional books, so I had many practice exams to choose from) and in the afternoon I often went to row in the Tigre delta.

In the evenings, Paul and I would work on my applications. It took us a while to decide where to apply—the choice of colleges was just immense. Finally, my Dad’s pragmatism prevailed and we chose 10 schools: four from the category ‘competitive’, four were ‘very competitive’ and two from the ‘most competitive’ list. The selection was more or less random—we really didn’t have a clue and just followed our instincts.

After receiving the application paperwork back from the schools, we realised how much work we had in front of us. Every school had a different set of requirements and most requested multiple essays, all of which had to be typed on a standard typewriter (we didn’t have an electrical one), in multiple copies, using carbon paper. It was a big challenge to ensure that the texts would fit into the allocated spaces on the application forms (once you started typing, there was no way back).

Paul worked with me with enormous dedication. What he lacked in formal education, he made up with his great gift for common sense. He had never had contact with a university, but he nevertheless was very good in asking the right questions: ‘What do you think their real question is here?’ ‘You’ve already talked about this subject in question 2, how about if we mentioned this in your response to question 4,’ etc.

I felt that my father was passionately alongside me. During the two months that the application process took place, all his free time went into helping me. Meanwhile, Lisl made it clear that she disagreed with my plan. She thought that I was ‘too young’ to study abroad and (correctly) suspected that if I went to college in the US, I would never return to Argentina. While Paul and I worked on the dining-room table, Lisl would pace up and down the room, constantly interrupting or making unhelpful comments. I never really forgave my mother for not having helped me at such an important time in my life. And I never forgot how much love and dedication my Dad put into a project that was so important for my future.

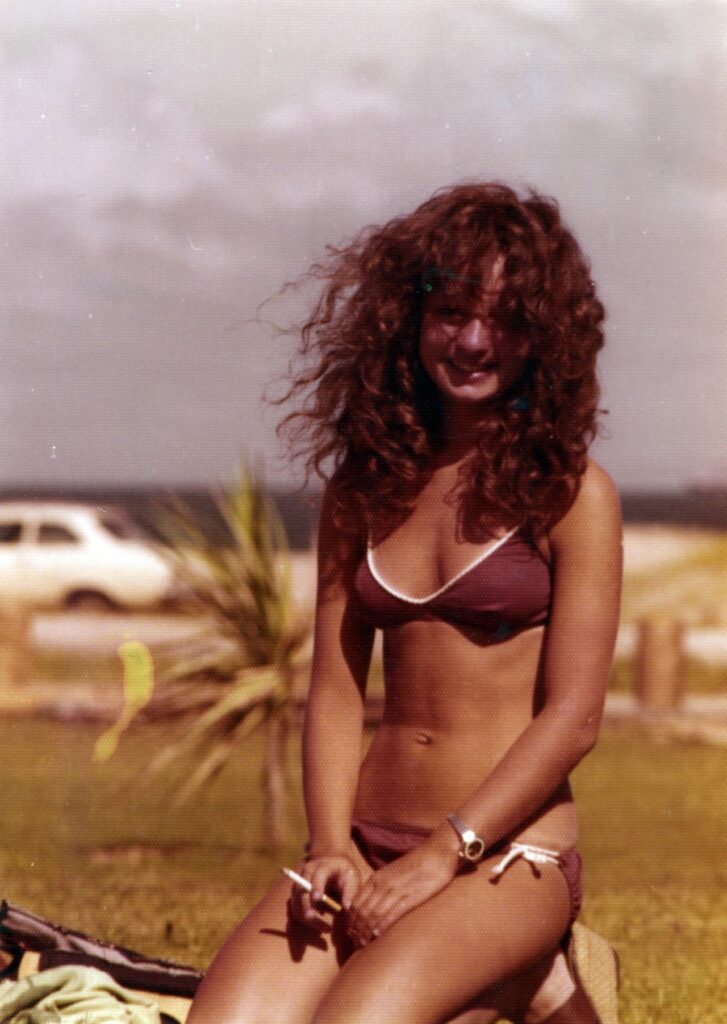

In December, after my applications had been sent in and the SAT had been taken, my hormones caught up with me. Graciela (Grapy) was two years younger than me, beautiful and uninhibited. We started spending nearly all our time together and traveling around Argentina in my first car—Annie’s Citroën 2 CV, which she had recently upgraded for a 3 CV and which she lent to me. It was a very old car, which frequently broke down and often needed to be started manually, with a lever, but I loved the freedom it gave me. Grapy had an identical twin, with whom I also spent considerable time, and to whom I naturally also felt very attracted to. It was mutual, which led to some confusion.

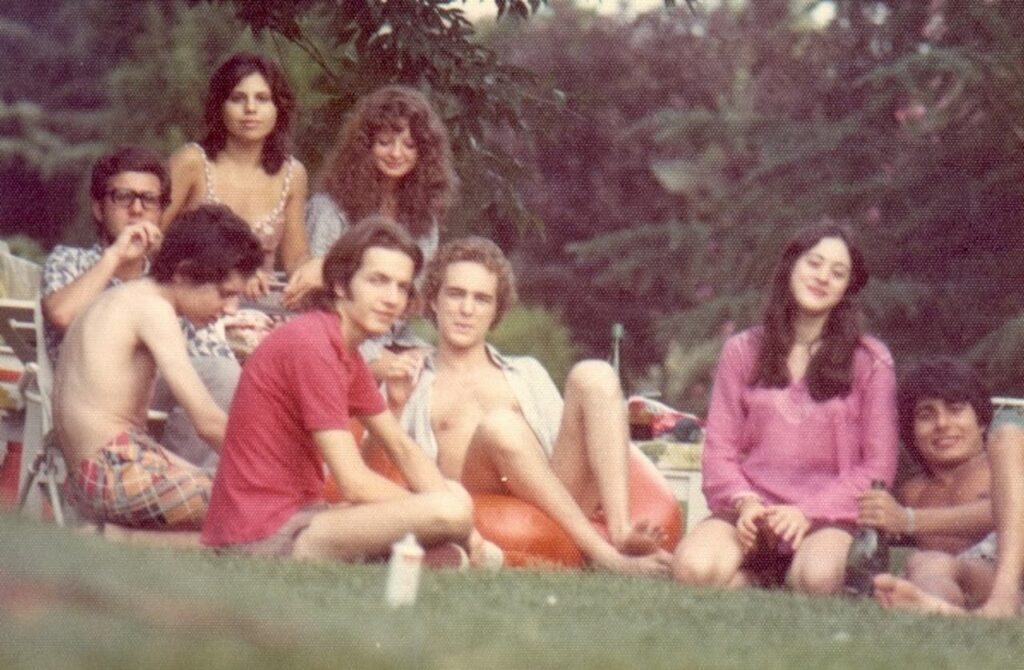

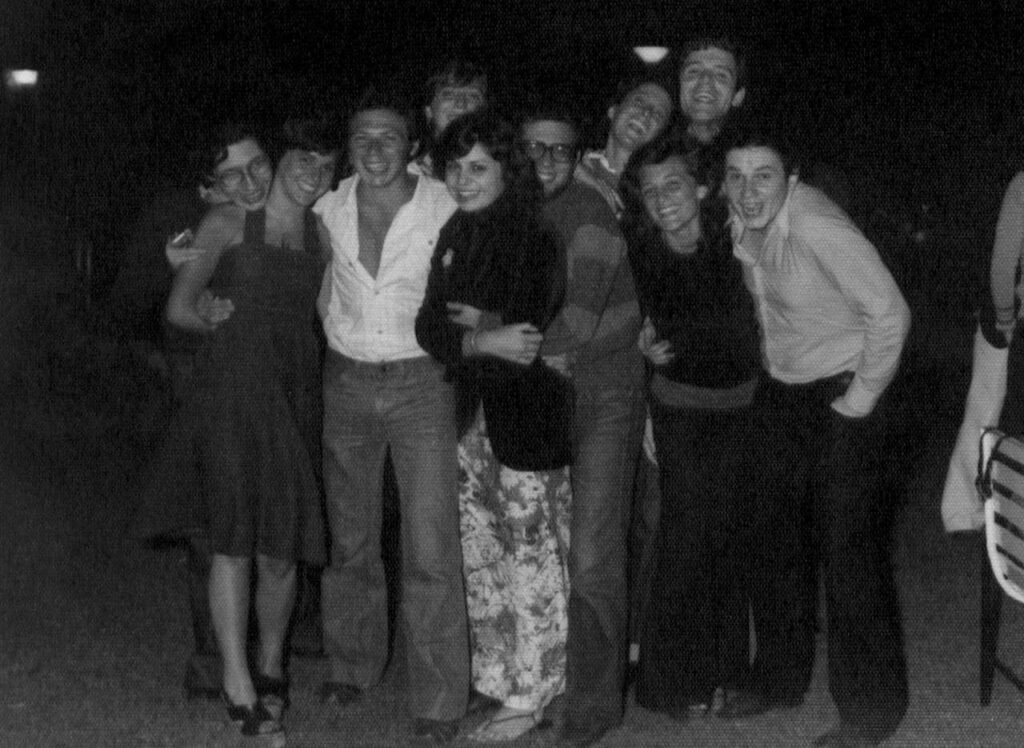

The parties at my house resumed, but they no longer had any political connotations. And alcohol, although in small doses, was now present.

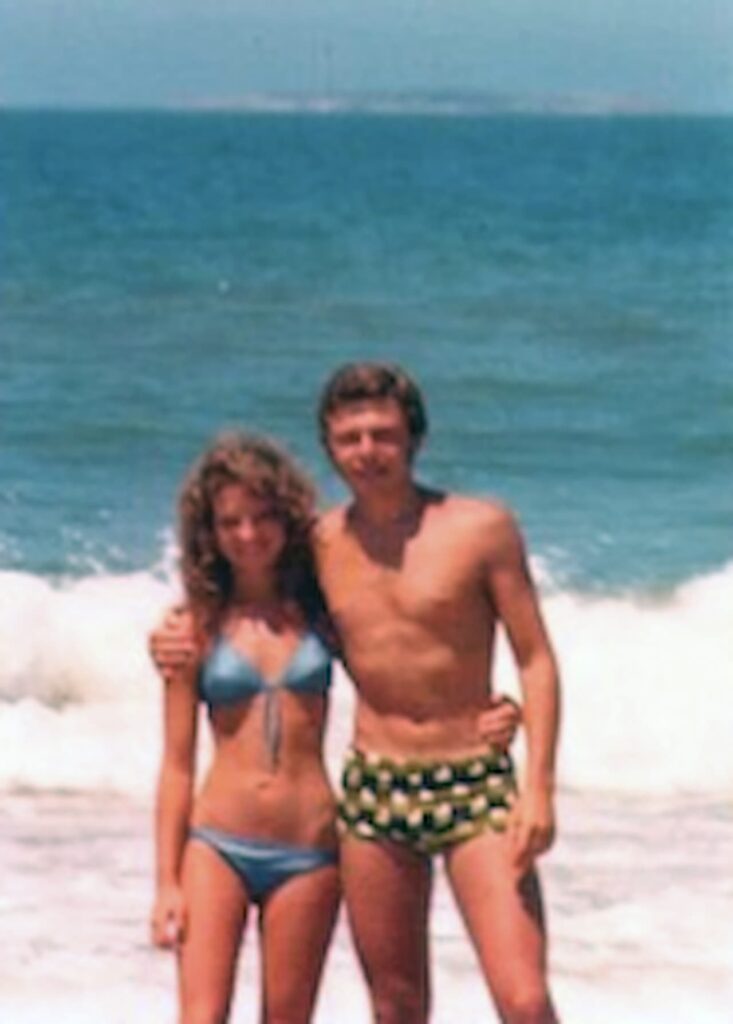

In January 1976, we went to Punta del Este, for the first time to the apartment that my parents had bought in the Edificio Opus Alpha. Grapy came with us. One afternoon, Paul returned from a walk on the beach and told me that he had bumped into an old acquaintance, an American lady. He had told her about my application to universities and she casually asked him when I would go to the US for interviews. ‘What interviews?’ my Dad asked. ‘Well,’ she said, ‘most good colleges will want to interview students before making a decision.’ My Dad and I had no clue that this was the case.

At the same time, the first response arrived—I was admitted to Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. Two days later another answer came, also positive, from Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois.

Paul’s instinct now told him that if I had been accepted so quickly by two universities, Northwestern being in the ‘very competitive’ category, there was a chance that I might make it into one of the very top universities. We discussed it and decided that I should travel to the US and visit five universities, including Northwestern, which was now my ‘safe bet’. So, I hastily wrote to these universities and in early February left for my first ever visit to the US.

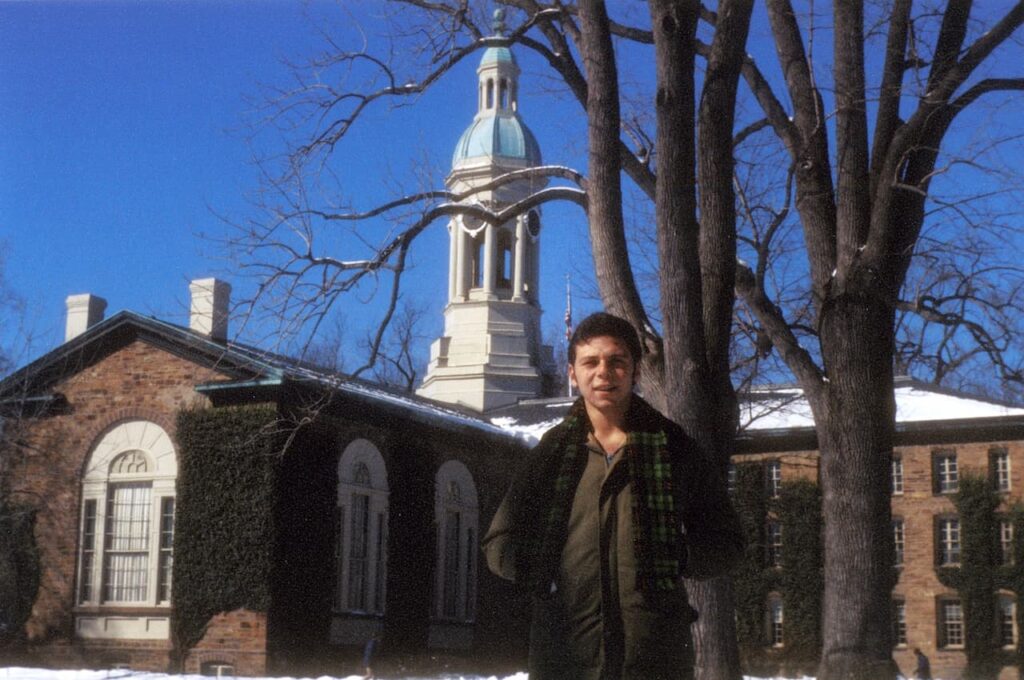

My first stop was in Princeton, which together with Harvard was one of the two ‘most competitive’ universities I had applied to.

I arrived on the Princeton campus in the early hours of a very cold morning, after a sleepless night on the flight to New York from Buenos Aires. As soon as I arrived, I started to look around the campus. The university had arranged for me to stay with an undergraduate student, who then took me to his classes and introduced me to the campus.

The following morning, after a short night’s sleep (I went to several parties), I had an interview at the Office of Admissions. I don’t have a precise recollection of the interview, but I found out later, when I was already enrolled as a student, what happened.

Apparently when my application arrived, the Admissions Office didn’t quite know what to make of it. They had never heard of my high school and were unfamiliar with the public education system in Argentina, since the few applicants who in the past had come from my country had all attended private bilingual schools. I had had no English language courses in secondary school, but the scores on the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) were very good. My SAT scores were mediocre and the teacher recommendations mostly incomprehensible (apparently some of my teachers, instructed by my father that they had to write in English, did the best they could, but just didn’t have the language skills to convey their message in anything else but Spanish).

But my essays were intriguing, ‘refreshing’ and in part ‘totally hilarious’, according to the Admissions Officer. What made the difference was my interview.

During our 90 minutes together, my interviewer was unable to say a word, let alone ask a question. I talked non-stop, explaining to him what an amazing place Princeton was. ‘Do you realise,’ I said, ‘that Firestone Library has the biggest on-campus collection of nineteenth century history books? And, you know, you can just walk in there and select any book by yourself. Do you know,’ I said, ‘that if Firestone Library, despite owning the largest number of books of any college in the US, does not have a particular volume, they will just order it for you, and you’ll get it in less than a week? By the way, did you attend the conference that Senator Williamson gave yesterday? You didn’t? Well let me tell you what he said about US foreign policy. Are you aware that the university has a mime society? It’s open to everyone, you should attend, it’s really great. For sure go in May, when Marcel Marceau, the world’s greatest mime is coming in person to teach a class. In case you missed yesterday’s lecture on “The Coming of the Industrial Revolution”, the professor showed us why it all started in Britain. It was very convincing. I later spent 20 minutes with him, and he gave me a list of articles I could consult on the relationship of raw materials with industrial growth. By the way, when was the last time you’ve been to the boathouse? Do you realise that the university just received two new racing boats? They’re in fiberglass, you know. They weigh 30% less than those in wood. I saw the lightweight team train and spoke to the coach, who allowed me to watch the training from his boat…’ Etc., etc.

After an hour and a half of listening to my monologue, the Admissions Officer signalled that time was up. I shook his hand, but mentioned on the way out that in case he had the time, today’s anthropology course on “Gender equality” was sure to be a hammer and that he should not miss it. ‘And, before I forget,’ I said, ‘there is a concert in the chapel at 7pm. The program includes the Monteverdi Vespers, one of the most amazing liturgical baroque compositions ever created. I can’t believe they’re producing it here on campus—you know it requires a choir of at least 20, does the university really have as many singers or are they reaching out to the Princeton community to complete the choir?’ At this point, the Admissions Officer had to politely, but firmly say that he was thankful for this exhaustive rundown on everything the university had to offer from this candidate-turned-university-salesman, but that he now absolutely, really had to leave for another meeting.

After having to relax with a cup of coffee following my onslaught, my interviewer recommended to admit me on the grounds that I would undoubtedly fit into the Princeton community and that, unquestionably, I would profit from the experience (if I didn’t die of a heart attack from over-involvement in campus activities). I would certainly challenge more than one professor, but he felt that I would have the intellectual honesty of accepting defeat in front of superior arguments. He also said to the full committee, that while he had never before encountered a more verbose candidate, I was also the most enthusiastic applicant he had ever interviewed, and that getting the campus fired up would not be such a bad idea for the rest of the undergraduate body.

I somewhat calmed down and caught up on my sleep for the rest of my tour of US universities, which included Harvard, Northwestern and UCLA. In the end I got admitted everywhere, except for Harvard, where I was placed on the waiting list. But by the end my trip, it was clear to me that if Princeton admitted me, that’s where I would go.

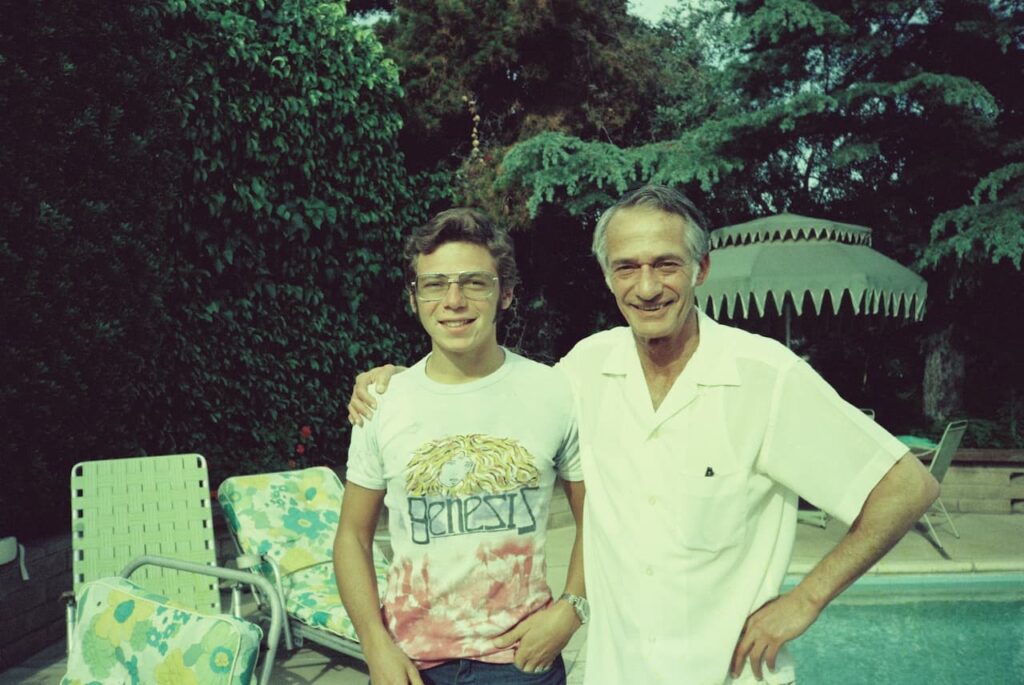

During my time in LA, I stayed with Alfred Lustgarten, my grandmother Annie’s brother-in-law. Alfred said to me that he played the violin in a symphonic orchestra, but while I was there, I never heard him practice. He had inherited a fairly large sum of money, was single after Annie’s sister had died a few years earlier, and was totally relaxed. He lived in a house with a large swimming pool, and spent a lot of his time drinking and/or at parties. He was very kind to me, showed me around LA, introduced me to dozens of people and was thrilled to have a (drinking) buddy around, even if only for a few days. When I returned to Argentina, Annie confided in me that Alfred had wanted to marry her after her sister had died. I understood why Annie had said no.

Upon my return to Buenos Aires in early March, Paul said that sitting around until September would not be a viable option for me, and that I should spend my time before leaving for the US by working at his office.

At the time, Simko SA was located in the Calle Corrientes, in very centre of town, not far from El Colegio. My father’s intention to get some work experience into me was a good one, and I was eager to learn, but he made the same mistake as his uncle Paul Wachsmann had made with him: he had me work on menial tasks only—making photocopies, addressing envelopes, copying information from one sheet to the next, verifying texts to ensure that there were no mistakes, etc. It was mindless work that bored me to no end. Neither did I like the ambiance in the office. Simko SA was full of people who sat around chatting, happy to do whatever was asked of them during office hours, but eager to go home as soon as they could. The employees were very friendly to ‘the owner’s son’, but I was turned off by the experience and began to behave like everyone else, focusing not on work, but on my after-work evening programs and my weekends with Grapy.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

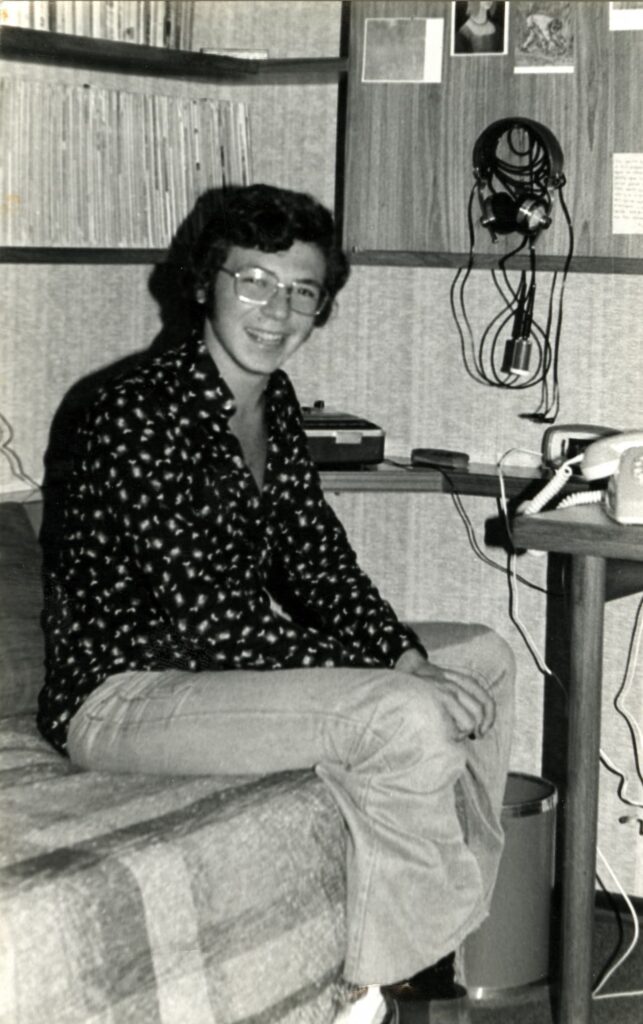

Pedro Simko