During my second year at El Colegio, one of our literature readings included ‘El Informe de Brodie’, a book that had only recently been released by the great Argentinian writer, Jorge Luis Borges. I had known Borges since I was a child, because Annie had been good friends with him. She had met him through her friend Paulino Keins, who appears in one of Borges’s short stories.

Borges would occasionally come for tea to Annie’s home. She would always invite me, prepare elaborate warm and cold drinks, as well as bake Borges’s favourite Viennese desserts. He was already blind at the time.

There are visually impaired people who, despite their handicap, are quite aware of their surroundings. Borges was not one of them. He would sit at the table and after a short exchange with my grandmother, pick up on a subject of his interest (it was nearly always related to literature), retreat into his world and start a monologue, which could continue for several hours. One thought would lead to the next, and he would cite whole paragraphs or complete poems in at least six languages, from authors I had never heard of. I was completely mesmerized by this always elegantly and well-mannered old man, who spoke in an unusual, high-pitched voice, but who had an interior life and a capacity for imagination that was spellbinding. My afternoons with Borges would leave a lasting impression on me and my love for literature, as well as my passion for ideas, comes from this time.

During one of the afternoons with Borges, I told him that I was very proud that our birthdays were on the same day—I was born on the day that he turned 58. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘it’s also the day when the Vesuvius buried Pompei in 79 AD, so I’m not sure how happy you should feel to have been born on August 24.’ He then spoke for hours about the human propensity to get fixated on dates, Einstein’s discoveries about time, how Nils Bohr had completely changed our perception of space and time through his analysis of subatomic particles, and how certain African tribes establish birthdates based on the moment of conception, not birth. He also spoke of the fact that in the universe, time did not exist, that it was a uniquely human invention. He finalised his talk by reciting in full ‘Los Conjurados’, the poem he had composed for Switzerland’s birthday in 1291, and which includes the famous line: ‘han tomado la extraña resolución de ser razonables’ (they have taken the strange decision to be reasonable). It was my first exposure to Switzerland and to its unique culture.

When we started reading ‘El Informe de Brodie’ at school, Annie suggested that I contact Borges and invite him to speak to us about his book. I called him, and he accepted on the spot. So on a sunny day, I picked him up at his home (he lived in San Telmo at the time) and we walked to El Colegio together. It was an unforgettable afternoon, which even today most of those present will remember.

Also during my second year at El Colegio, a major event took place in Buenos Aires: the semi-final of the World Chess Championship, a competition between Tigran Petrosian and Bobby Fischer. The matches took place at the Teatro San Martín. A giant chessboard was placed outside the building, where hundreds of chess fans gathered to analyse every move by the great masters. My friend Alfredo López (who we called El Negro) and I would regularly skip classes to join the crowd and discuss the games. We would then go to the Salón Capablanca in the city centre, and play a few games ourselves (if we could get a table—chess fever had reached such a state in Buenos Aires that you had to stand in line and sometimes wait for hours before getting to play). On the way home, El Negro and I would play a few games on the train, on a small magnetic board that my father had given me.

I wonder how many teenagers today are skipping classes to play chess? It’s a game that is great for the mind, where luck plays no role, but it requires time and patience to play it well. Our digital age is all about speed, and I often wonder how good that really is. Chess taught me patience and foresight, virtues I think we might not have enough of in today’s world.

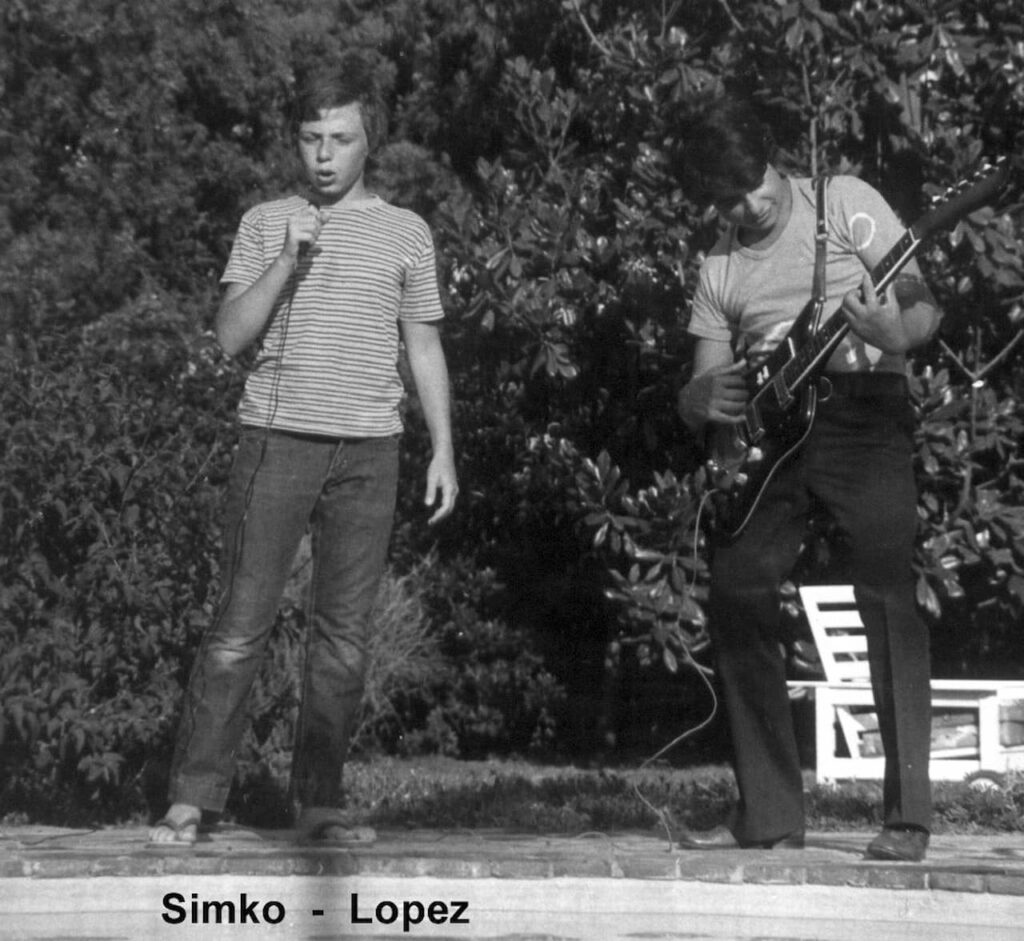

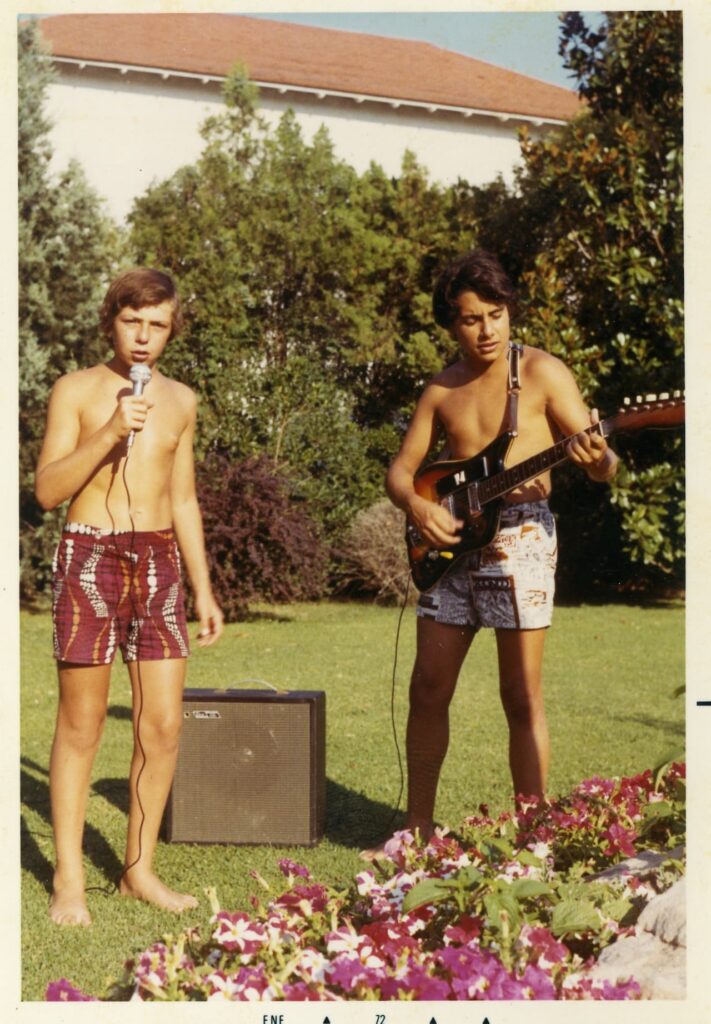

El Negro and I saw each other frequently. We lived not far away from each other and we shared a passion for ping pong and music, in addition to chess. I had not yet mutated and had a good voice, while El Negro played the guitar very well. On more than one afternoon, we would put the amplifier by the pool and imagine ourselves playing in front of large crowds of adoring fans.

In the spring of 1972, my friend Cecilia suggested that we go to see Maurice Béjart’s ballet. I quite fancied her, and didn’t want to miss an opportunity to have an evening out with her. But watching ballet, I thought, would be a high price to pay. I had seen classical ballet in the Teatro Colón with my parents and thought it was the most boring thing I had ever come across. But the evening watching Béjart left me spellbound. The show finished with Jorge Donn dancing to Maurice Ravel’s ‘Bolero’. I didn’t want the music or the dancing to end. It was an evening that transformed me. My appreciation for modern dance never ceased from that moment on. I told this story to Maurice when I met him more than 25 years later in Lausanne. He remembered the performance in Buenos Aires very clearly, even commenting on small details that I had long forgotten.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko