In June of 1991, I invited Josée on a surprise trip to Rome. I had something important to tell her and wanted to do so outside of Geneva, in what I hoped would be a romantic setting. Over dinner, in a restaurant with a beautiful view of the Villa Borghese gardens, I asked her to have a child with me. I said that we were getting older (I was 34 at the time, she was 31), we had been married for over six years, were settled in Geneva, and I thought that the time had come to found a family.

She hesitated. Josée had never been convinced that having children was a good idea. And, she said, shouldn’t we be waiting for a while, we’ve only just started our business. I responded that there was never a perfect time to have children, that events could always get in the way, but that I felt the time was now. In the end, Josée agreed and fell pregnant in the following weeks.

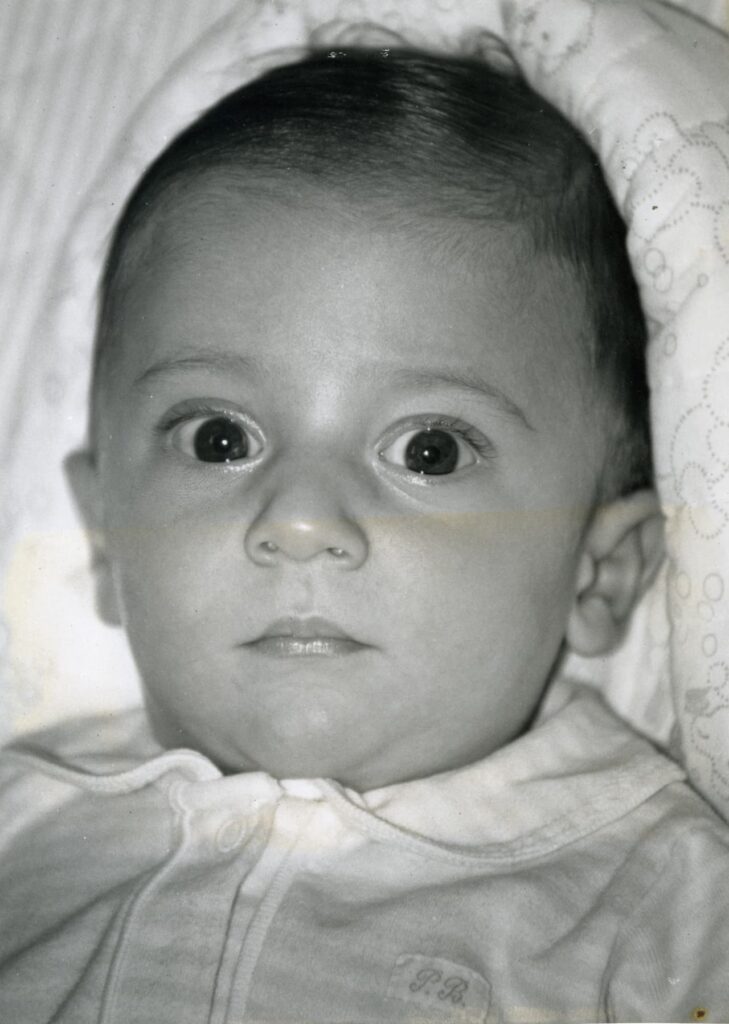

Pablo Alexandre Simko was born on March 16, 1992. Josée’s pregnancy was uneventful and she insisted on working till the very end. Pablito, as we’ve always called him, received his name from my father, who at the time was still using the Spanish version of his name (after settling in the US, he reverted to Paul, his childhood name).

We wanted to honour my father because it was his first grandchild and because he had always, unfailingly, been by our side. To me, he had been a guide and a best friend. And he had welcomed Josée into our family with open arms. My father was totally overcome with joy at the birth of Pablito, arrived in Geneva only a few days after he was born, and would become a stellar grandfather.

Pablito was born with a lot of hair on his head and wide-open eyes. Conveniently, he arrived in the middle of the day, allowing me to send the 200 cards we had addressed, but of course not yet finished printing, before the day was over. In the evening, I held him in my arms and we sat together for a long time. It’s a feeling I’ll never forget.

Nicolas Miguel Simko was born on April 26, 1994. He was named in honour of Nico Issenmann, our boss at Jacobs Suchard, who had remained a close friend, a board member of Simko. He also became one of our son’s godfathers.

From the start, Nico (as we’ve always called him) was an easy-going and luminous child. Pablito could sometimes be tense and have the occasional tantrum. Nico, on the other hand, was a relaxed and happy boy, who delighted us with his charming ways.

At the end of Year 1, Simko Communication & Marketing had achieved a turnover of CHF 350,000 and a profit of CHF 20,000. In truth, it was very little, but I had initially set an objective of CHF 300,000 and no profit, and so felt ecstatic. It was enough to sustain us financially. Josée was pregnant with Pablito and during Christmas of that year, which we spent at our chalet, I felt relaxed, happy and looked to the future with great optimism.

We started to hire personnel. In keeping with the rest of our unfocused approach, we hired either recently graduated university students, who were attracted to the glamour of advertising, but knew nothing of the business, or marketing experts, who also had no experience with creative advertising. The result was that no one in our office (including of course Josée and myself) had a clue about advertising. In hindsight, it was a bit of the deaf leading the blind.

But the business kept growing. In 1992, we started to work for the Geneva Stock Exchange. We initially did their annual report, then one brochure after another. Creatively, it was nothing noteworthy, but I knew how to send bills and the Stock Exchange had lots of money. The consequence was that financially we were very well off—there was a year when 20% of Simko’s turnover was made by billing the Geneva Stock Exchange for changes to the texts they had sent to us as ‘final’, but at the last minute had wanted to make corrections to. I had set up a whole team of graphists and publishers, and secured margins at every step of the process.

By 1994, we were billing over CHF 1 million per year and making a healthy profit, but what we produced was not noteworthy. My team was great at client handling—very responsive, very reliable and I developed excellent relationships with all clients, but the output was inconsequential material. We made good money with whatever we could sell to clients, and I was very good at stimulating demand. Whenever I sensed a revenue opportunity, I would schedule a ‘review meeting’ with a client, present an analysis of his business in whatever area I thought there might be an opportunity for us, and then sell something, whatever it was. For some clients it might have been a new brochure, for others it was an event to celebrate the launch of a new product, for others a new way to produce advertising material at a lower cost (but at a high margin for Simko); for still others it might have been an internal communication campaign. It worked. Clients were impressed by my entrepreneurial attitude, the often eye-opening analysis I gave them and rewarded me with new business.

In 1995, the Geneva Stock Exchange merged with the Basel and Zurich Stock Exchanges to form the Swiss Stock Exchange. At the time, the Geneva Stock Exchange represented 30% of our business and the threat of losing it was very real.

The Swiss Exchange decided to organise a pitch amongst the Geneva, Basel and Zurich agencies, plus two or three additional agencies they considered ‘hot’. We were the only non-Swiss German agency. The pitch instructions and all other documents, as well as the face-to-face briefings were in German. We were invited out of politeness and because of the Swiss Germans’ belief in democracy and federalist values, but it was obvious that we had close to a zero chance of winning.

One of the tasks required for the pitch was to find a way to better integrate the newly created Swiss Stock Exchange logo into the graphic material the client was starting to develop for the launch. This seemed like an easy task, but when my team and I started to take a closer look, it became obvious that there were serious problems—the logo had been conceived independently of its graphic applications, and it simply didn’t work.

One day, one of the graphists assisting us on the pitch showed me a new logo, a creation he had made. It was modern, beautiful and it worked on all applications. My initial thought was: It’s not what the client wants, it’s a waste of time. And the written instructions said in bold letters: do NOT make any changes to our new logo, it has been approved for launch! But then I thought again: It’s our only chance; the rest of the agencies, in good Swiss German fashion, will just follow the client’s instructions and find convoluted ways of applying a lousy logo. This is our chance to be bold and different and, anyway, with such slim chances of winning, it was a risk worth taking.

We were the third agency to present to Antoinette Hunziker, at the time the Swiss Exchange’s Marketing Director, later to become the CEO. I showed up to the meeting with no tie and a bright red handkerchief around my neck.

When we got to the item concerning the graphic application of the logo, I said: ‘The problem with the application of your logo is not the graphic environment, it’s the logo itself—it’s just a collection of words and it disappears once you apply it anywhere; it’s repetitive and gives the impression that you couldn’t make up your minds which language to use, so you just inserted into the logo all languages’. To make my point, I proceeded to show one application after the other of the logo that the Swiss Exchange had developed. It was clear that it was lost and not visible.

‘But there is a solution,’ I then said, and showed the new logo we had developed. Before anyone in the astonished marketing team could object that the logo had already been approved and therefore was not a subject for discussion, I presented the same material we had just seen, but with the new logo we had created. I then showed more material, reflecting how the new logo would look on new surfaces, including the building’s façade. Finally, I took off my red neck scarf and offered it to Antoinette—it included, beautifully embroidered, the new logo.

Antoinette looked at the scarf, asked me to show her again the new logo and its applications. She then went to the phone and called her Assistant: ‘Mrs. Müller,’ she said, ‘how many more agencies are scheduled to present? And when are they due to come in? Please call them and cancel. We have a winner.’

She then walked over to me, shook my hand and said: ‘Well done. Can you come in tomorrow to show the new logo to our CEO?’

Over the following five years, the Swiss Stock Exchange would represent up to 50% of our turnover and even more of our profit. The advertising trade press, and even the Swiss financial press, mentioned our win and talked about the new logo. Every time anybody entered the building, they would see it. I gave press interviews and explained how our ‘Swiss French’ approach to communication had made the difference.

The Swiss Exchange pitch taught me an important lesson: If you want to win in the advertising industry, don’t follow the rules, it’s the mavericks that make it big.

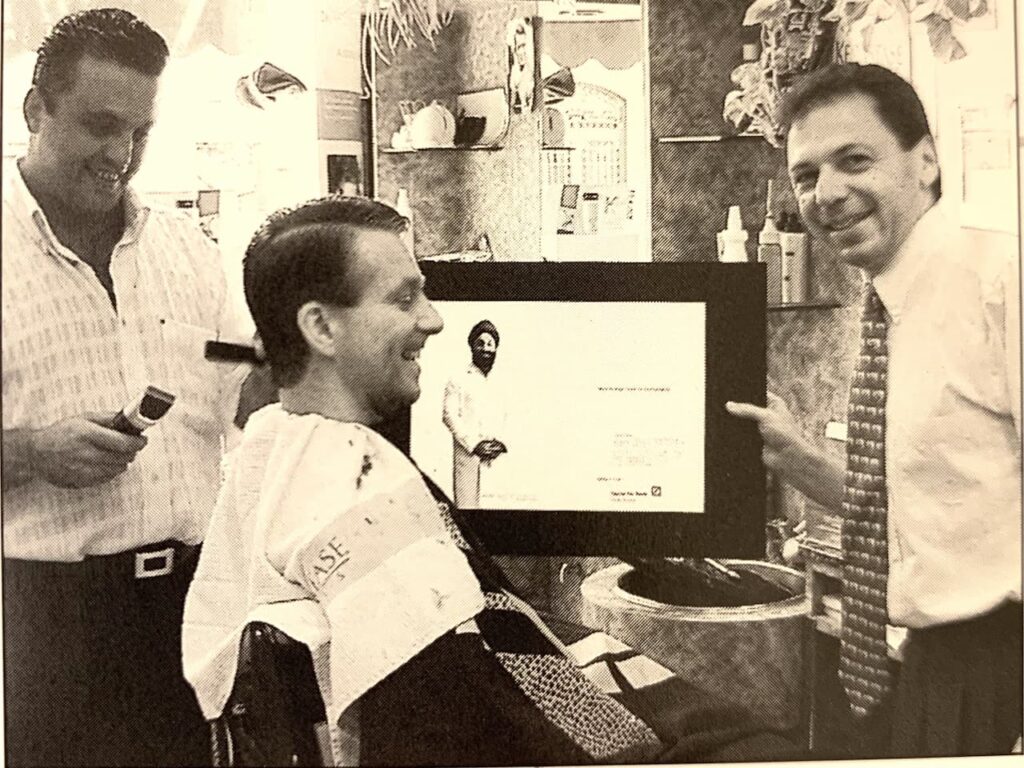

I began to behave in cheeky ways and made sure that the press heard about it. This included the hilarious sale of an ad campaign to Deutsche Bank at the coiffeur.

We had been working for Deutsche Bank Private Banking for a while, doing brochures, events and smaller printed material. Then we had the idea of creating an ad campaign, which would be shown worldwide. We presented our first sketches to the marketing team, who were enthusiastic. We were ready to produce it, and had a window of opportunity to do so over the coming two weeks, when I was told that the campaign needed the approval of the CEO. That was a major stumbling block, because the man in question had back-to-back meetings scheduled for the next three months. ‘It’s impossible to get into his diary, worse than that of a Head of State,’ I was told.

I called the CEO’s Assistant, pleaded with her, but got nowhere. In the end, I asked her if Herr Scheidt ever went to get his hair cut. ‘Of course,’ she said, ‘like everyone else.’ ‘When is his next appointment?’ I asked. ‘Funny you ask,’ she said, ‘he’ll be at the coiffeur this afternoon at 3pm.’ That’s all I needed to know. At 3.15pm, my team and I arrived. I presented the campaign to Herr Scheidt, who approved of it wholeheartedly (after the coiffeur himself had nodded in agreement) and the campaign was on air less than a week later. The press reported the story and our reputation grew as an agency that got things done, no matter the hurdles or the difficulty.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko