In early 2003 we were invited to pitch for the global business of Tag Heuer. At the time, it was one of the world’s best-known watch brands. It had been supported for years with the iconic ‘Don’t crack under pressure’ campaign, and it was a very big honour to be invited to such a competition. Five agencies were asked to present, all of them from large, international groups plus Simko. We were the only independent and the only Swiss agency in the pitch.

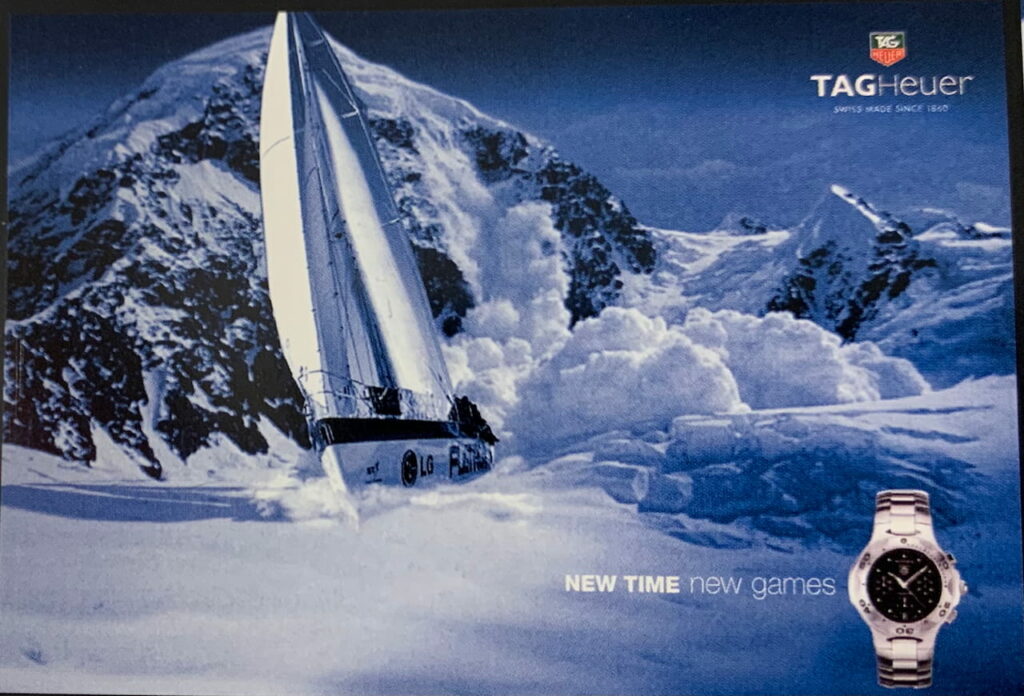

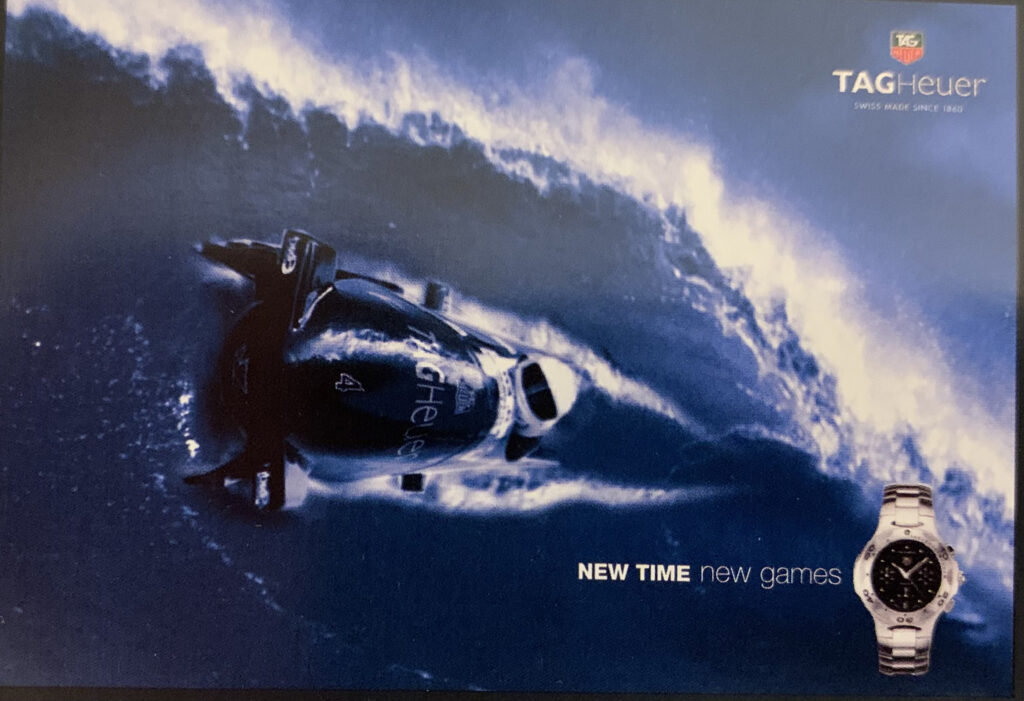

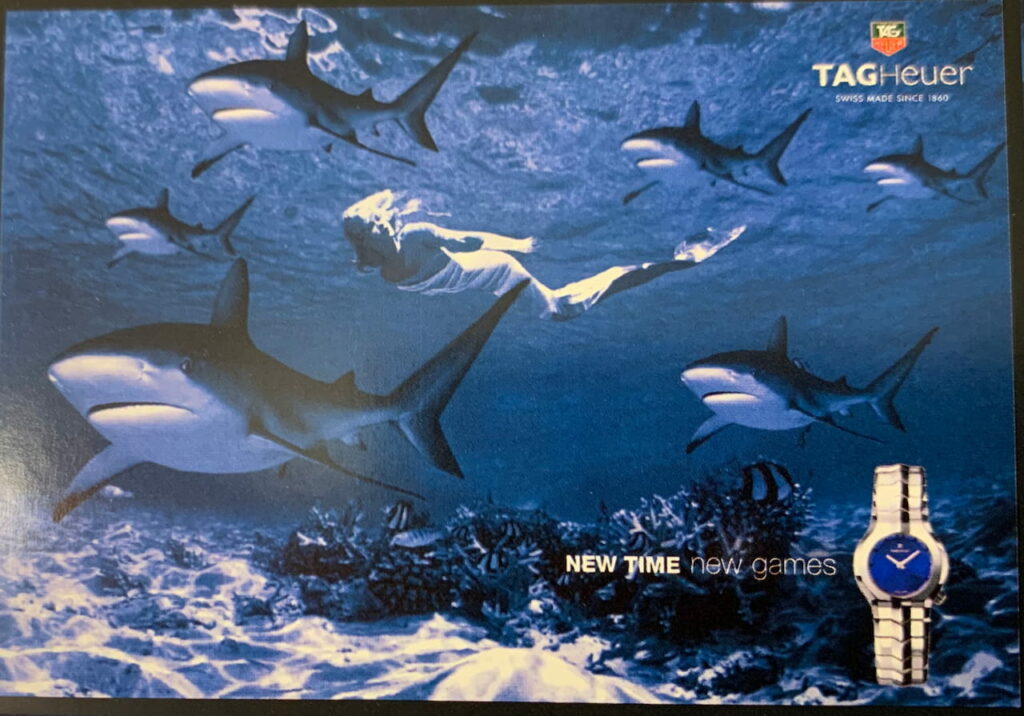

Olivier and his team came up with an absolutely stunning campaign, positioning Tag Heuer as the ultimate sports brand. What you saw, were images of future, imaginary sports, including sailboat races on glaciers and bobsleigh-competitions in the sea. We contacted the world-famous film director Ridley Scott, who had recently released ‘Gladiator’ and he agreed to produce the film we had in mind.

Our presentations, into which we invested considerable sums of money, looked extraordinary and the client was totally impressed. We were asked to produce enough material for a worldwide consumer test. Our work was presented in competition to an idea created by TBWA in Paris, one of the world’s best-known creative agencies, the people who had been running the Tag Heuer account for the prior 15 years and had created the ‘Don’t crack under pressure’ campaign.

Our campaign won in every country it was tested, including Japan, the US and the UK. The CEO called, congratulated us and said that we had won the business. A few minutes later, he called again, saying that we should keep our win quiet, since it was a big deal and that he would tell us how and when to communicate after he had met with the CEO of LVMH, one of the world’s largest luxury conglomerates, who had recently acquired Tag Heuer.

A week went by, then another. I tried to reach the CEO, but my calls were not returned. Finally, after three weeks, he called me. He said that he preferred not to beat around the bush or tell me an inaccurate story: the LVMH CEO had said that he would never allow Tag Heuer, the crown jewel of his watch brands, to be managed by ‘a no-name agency based in a no-name country’. The Tag Heuer CEO was ordered to continue to work with TBWA, a global agency he was familiar with, and which had offices all over the world.

After a few days of depression, it suddenly dawned on me that the LVMH CEO had actually done us a favour by taking what appeared initially as a totally unjust decision. Looked at positively, the Tag Heuer message was: Simko has enormous potential, but we wouldn’t be able to do work for great global clients, if we didn’t belong to a large group with a well-known name and offices around the world.

In the following months, I was contacted by three leading global agencies: McCann Erickson, TBWA and Saatchi & Saatchi. The story of Tag Heuer, as well as our win of Switzerland’s Campaign of the Year Award, had made the rounds in the creative industry and all three groups were keen to acquire us!

McCann were best organised, TBWA put the most money on the table, but we sold our business to Saatchi & Saatchi because I felt best with them. Kevin Roberts, Saatchi & Saatchi’s global CEO (who coincidentally had also started his career at E&SO in Geneva) came to visit us and we immediately hit it off. He wandered around the agency and played fussball with the creative team. I took Olivier with me to meet the leadership team of Saatchi & Saatchi in London, and it became instantly clear that we all spoke the same language. I felt that the Saatchi culture best matched us and that our team (and I) would have the best chances of developing ourselves in the Saatchi environment.

Little did I know at the time that the decision to join Saatchi would ultimately also be by far the most lucrative. After a short negotiation with Publicis Group (who owned Saatchi & Saatchi), we agreed on an earnout mechanism, which made payments strongly dependent on how well the new entity, called Saatchi & Saatchi Simko, would perform over the following three years. Our business did so well that the final price paid was more than twice as much as McCann and TBWA had originally offered us.

I was very busy running the agency, but my weekends continued to be totally dedicated to Pablito and Nico. They were both developing very well. More and more, their lives began to revolve around fencing, a sport in which they both excelled.

The Club d’Escrime de Genève, conveniently located within walking distance of our home, absorbed a lot of their time and on weekends they would often participate in national contests. I was so happy taking them to these competitions, which often involved overnight stays in different parts of Switzerland. I loved these trips, which allowed me time alone with the kids, and also time to myself (the competitions took many hours, giving me time to read or just doze off).

During one of the weekend trips to participate in national competitions, and after Pablo and Nico had once again won gold medals, the trainer came to see me. He said: ‘I don’t think that I can continue training your boys.’ ‘What do you mean?’ I asked. ‘They have great potential,’ he said, ‘but they are not Swiss. Their next step is to participate in international competitions, but I cannot have them on the team if they don’t have the Swiss nationality.’

At the time, Pablito and Nico were Austrian, Canadian and Argentine citizens, but not Swiss. Switzerland accepted double nationalities, but Austria didn’t, and I thought it would be unwise for the boys to lose their European Union passport. There was a way for Austria to accept a double nationality, but it was a difficult process and involved the approval of the Austrian Parliament. But I was determined to help the boys continue with their fencing career, without putting at risk the opportunities that the EU represented for their futures.

After several months of complicated procedures and paperwork, I finally was invited to present my case in Vienna. I was told that if the double nationality was awarded to me, my children would obtain it automatically too.

On a Monday morning, I appeared in Vienna, in front of a commission of four parliamentarians. To be allowed double nationality, you had to prove that not obtaining the nationality of your new country would produce severe prejudice to you and that, likewise, to lose the Austrian nationality, would create drastic issues for you.

I produced a letter from the President of the Swiss Association of Advertising Agencies, in which he explained that the Association would like to have me join their board, but that I couldn’t do so if I wasn’t a Swiss national. This clearly proved that my business prospects were at risk if I didn’t become Swiss.

‘I understand why you need to become Swiss,’ said one of the parliamentarians, ‘but why do you need to keep the Austrian nationality? You have never lived in our country.’ I responded in German: ‘Isn’t it surprising to you that I’m completely fluent in German, despite the fact that the last Simko who lived in Austria left almost 70 years ago? My children also speak German fluently, even though they, like me, never lived in Austria.’

I then produced a photo of my library, which includes dozens of volumes of Fritz’s books. ‘This,’ I said, ‘is my grandfather’s library, part of which he took with him to the trenches to defend the Austrian nation during World War I, and which then accompanied him to Argentina. May I remind you,’ I said, ‘that my parents and grandparents didn’t leave Austria in 1938 for tourism—they fled for their lives, and I wouldn’t be standing here in front of you, if they had not succeeded in escaping the persecution that your ancestors instigated. If you don’t allow me and my children to keep the Austrian nationality, you will cut us from our roots and you will continue perpetuating the injustice that my parents suffered.’

There was a short silence, then the president of the commission said: ‘Your request is approved.’ In the following days, I received a very rare and official document, which has allowed us to remain Austrian, while also being Swiss. It’s such a rare document, and there are so few exceptions, that when Pablito, Nico or I have to renew our passports, it always takes a long time, while the consular authorities in Geneva and Bern double and triple-check the veracity of this document.

The boys were jubilant to become Swiss, but at the time didn’t care much about the fact that I had been able to retain for them the Austrian citizenship. Over time, however, the Austrian nationality came in very handy, especially to Pablito, who in 2015 would have been unable to obtain a job at the European Commission without it.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko