One of the things I really loved about my job in advertising was the insights my clients gave me into consumers and their behaviour. I was fascinated by what brands and brand consumption indicated about people in the real world. One of the most revealing insights came from the lottery.

For a while, we had small assignments from the Swiss Lottery, enough for me to see their marketing manager from time to time. On one of these occasions, I casually asked him about the winners of big lottery tickets. ‘Tell me about them,’ I said.

‘Well,’ the man said, ‘we have a special unit that takes care of them. ‘What do you mean?’ I said. ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘we have a team of psychologists that chaperones the big winners.’ I looked puzzled, so he said: ‘The people who play the lottery are dreaming of changing their lives. If they win a small sum, then that’s OK, but if they win a lot of money, then what typically happens is that they quit their jobs, buy a large house (often in a new neighbourhood) and then leave for extended periods of time on luxury trips to “see the world”.’

‘When they come home from their travels, they are often aimless. They have lots of free time, but don’t really know how to make the best use of it. They can’t see their old friends because they are at work. And anyway, their old friends feel estranged from them. New friends often appear, who all too often are not really interested in them as people, but who value their money.’

‘Over time, many of the people who win big tickets in the lottery get depressed and it’s not at all rare that they commit suicide. That’s very bad for our business, so our psychologists coach them to prevent the worst.’ ‘Do you usually succeed?’ I wanted know. ‘Not very often,’ he said. ‘Most people who win large amounts in the lottery are very unhappy afterwards. The lucky ones,’ he added, ‘lose most of the money they won and return to a healthier lifestyle afterwards. The others are like King Midas—wealthy but miserable.’

The insight from the lottery winners was not a surprise to me, but it did give me to think: How often do we ask for things that wind up being useless to us, especially material things? It’s so critical, I thought, to focus on what’s essential in life. We don’t always realise that change, any change, brings with it consequences, and these may not be what we want.

During the years when I was growing Simko’s business, I was working very hard during the week, often getting up at 5.30am and leaving for Zurich with the 6.32am train. The evening before, I would load a large attaché case with dozens of magazines and newspapers, which I diligently read in the train, in the hope of identifying new business leads.

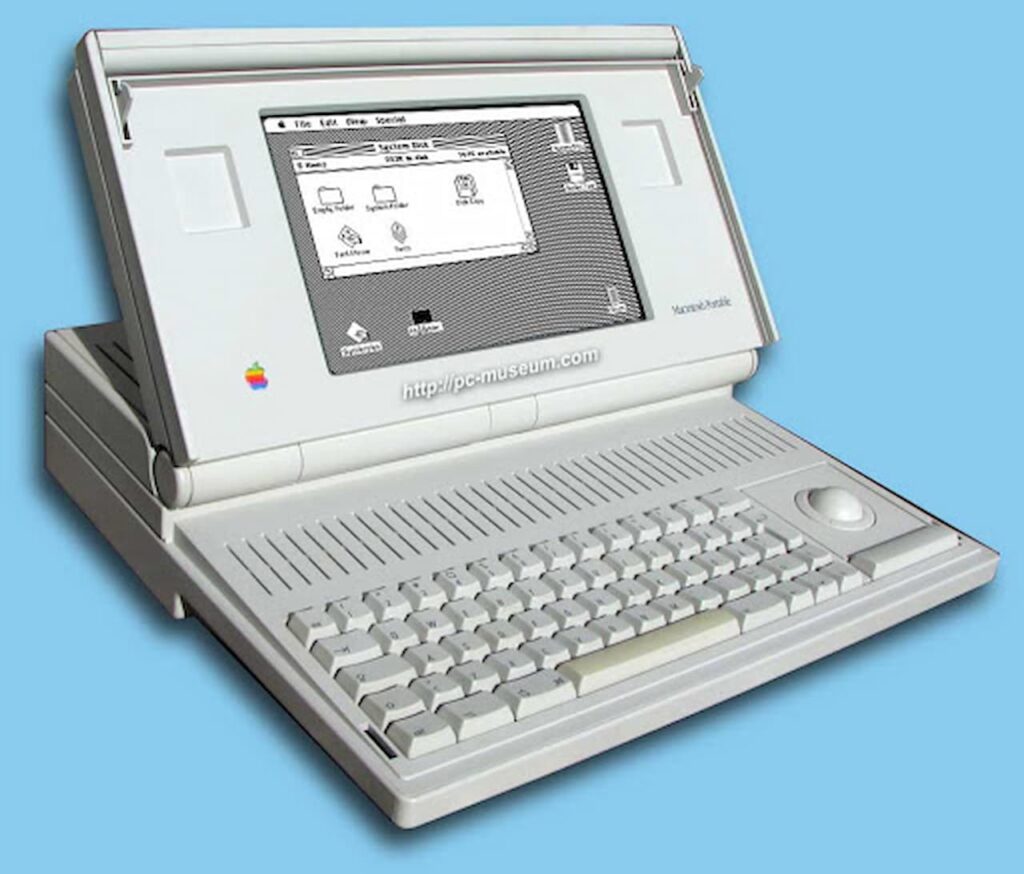

From 1992 onwards, I always carried with me a portable computer. The first one we acquired, for about $ 3,000, was a Macintosh that weighed 8kg, had a maximum autonomy of 2 hours and a tiny black & white screen, which was not backlit.

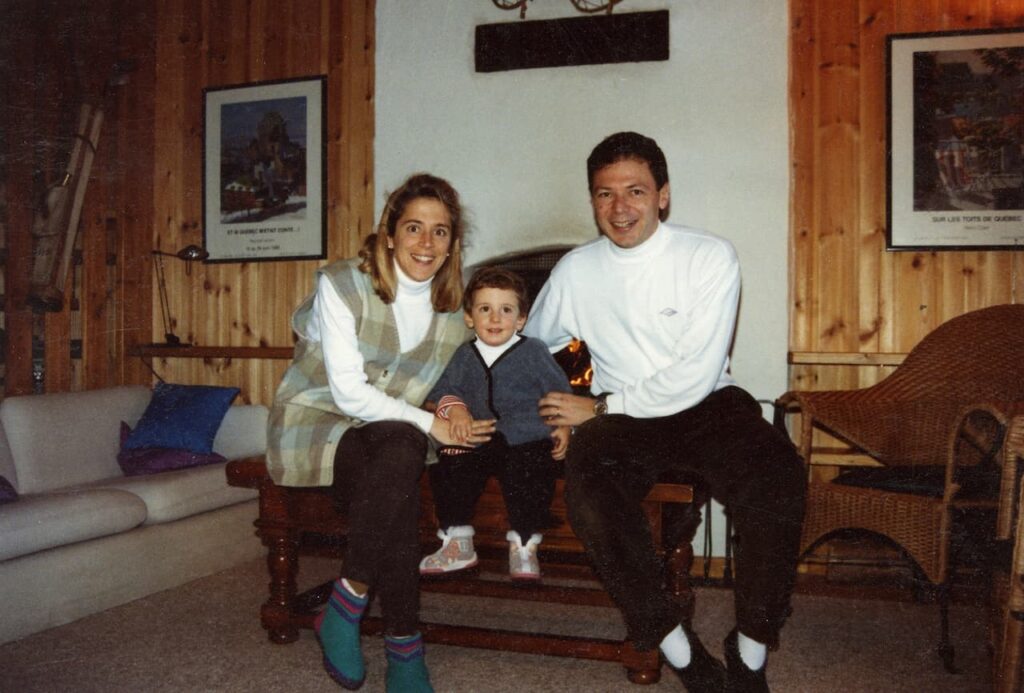

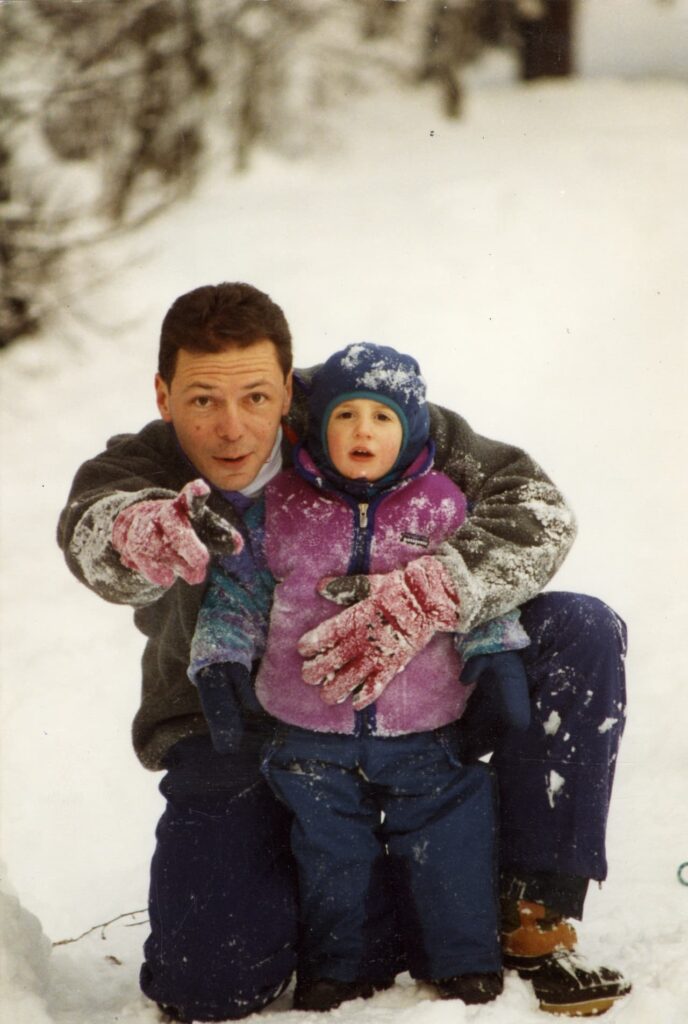

During the week, I rarely returned home from work before 7.30pm. But all my weekends were devoted to the family. In the time before smartphones, it was uncommon to work on weekends and I certainly didn’t. I was devoted the kids and loved to spend time with them.

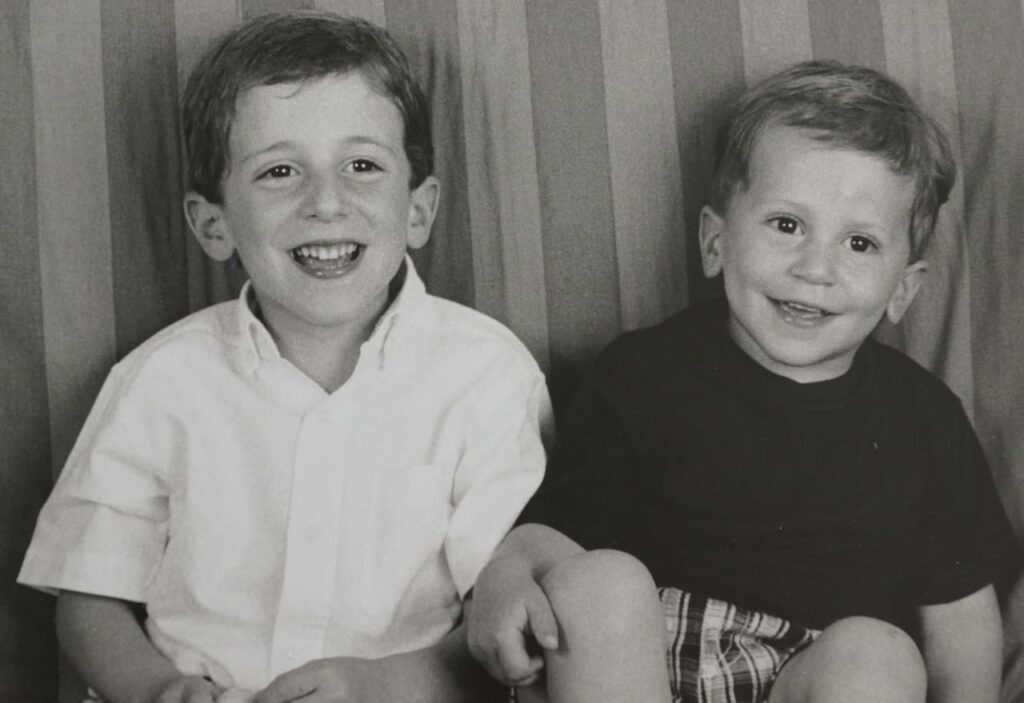

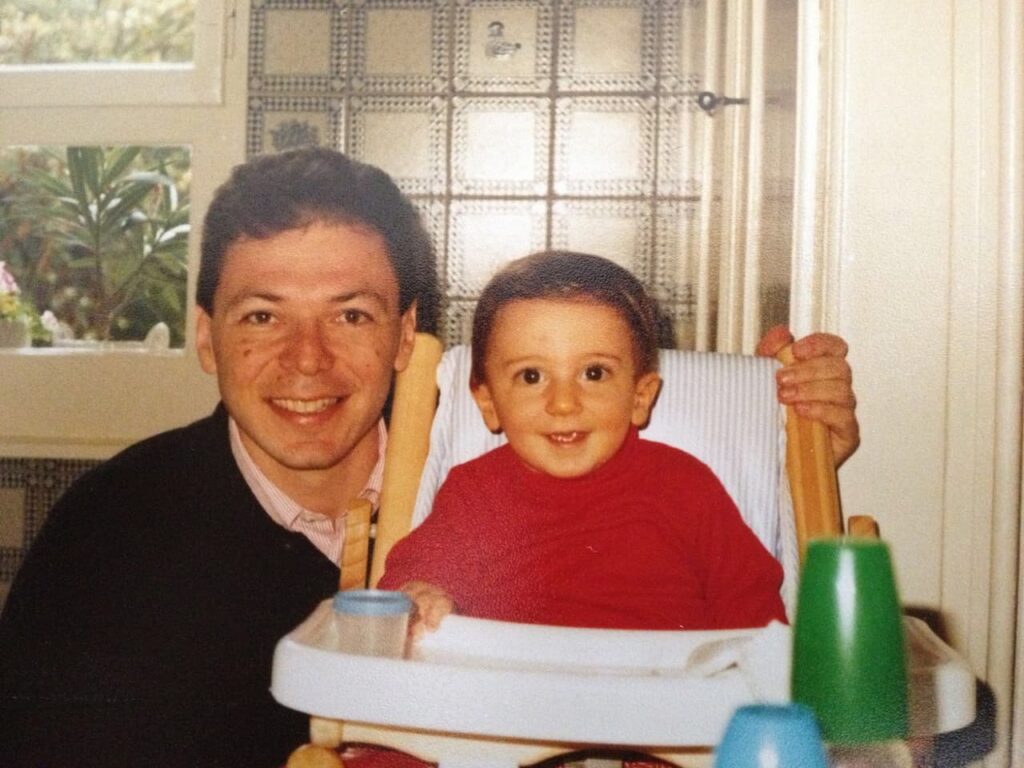

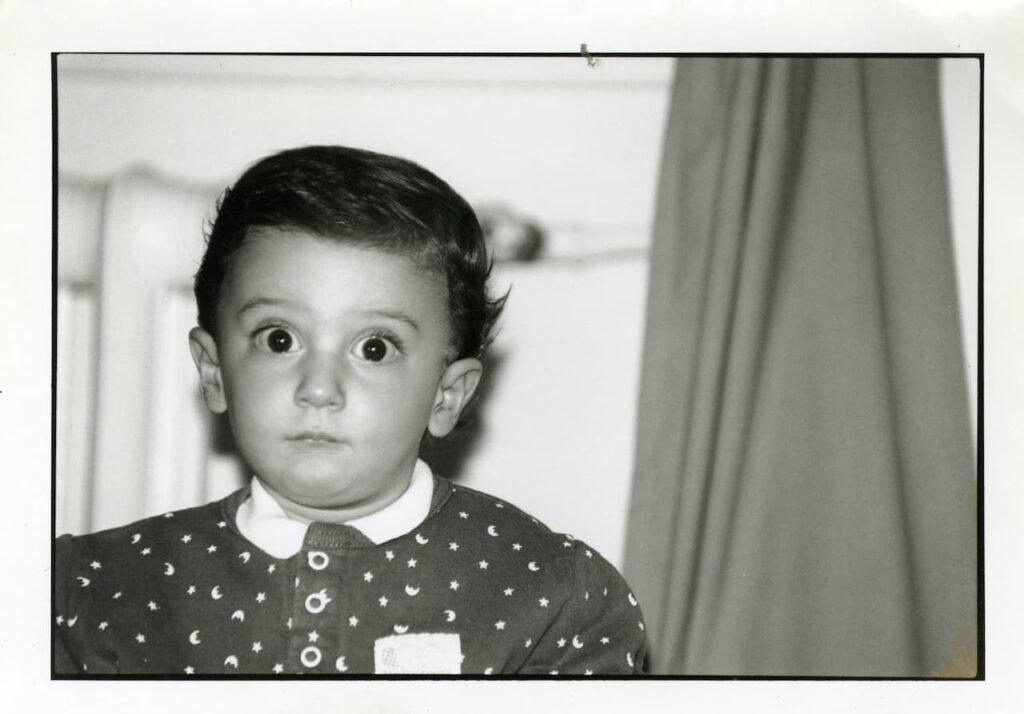

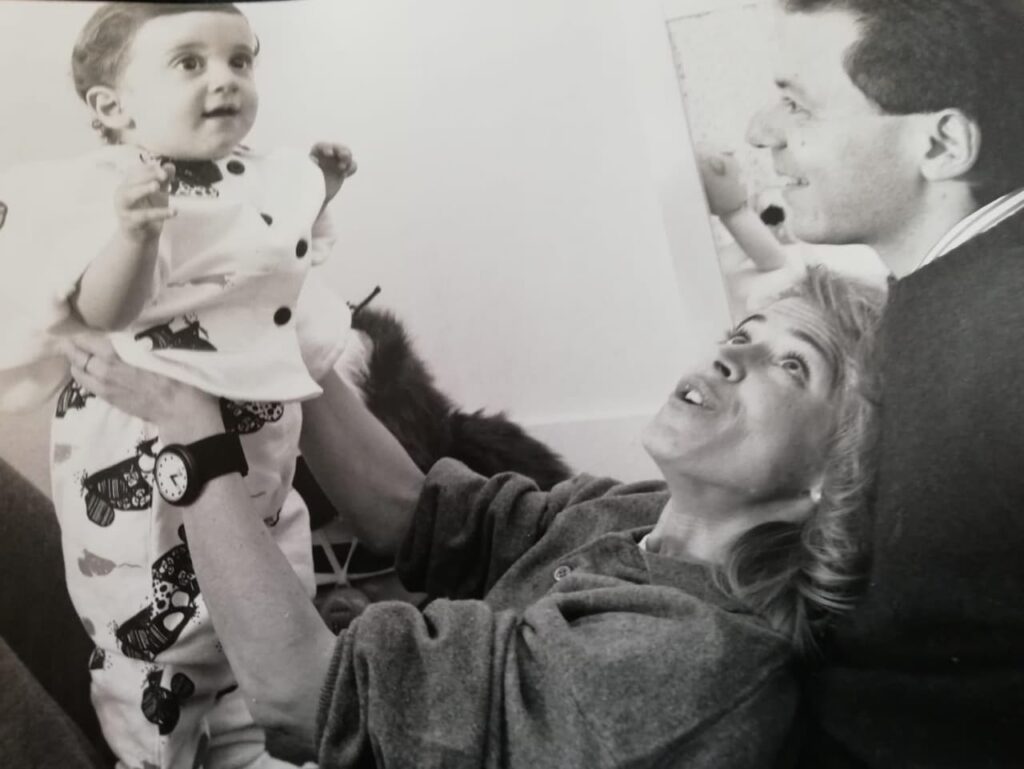

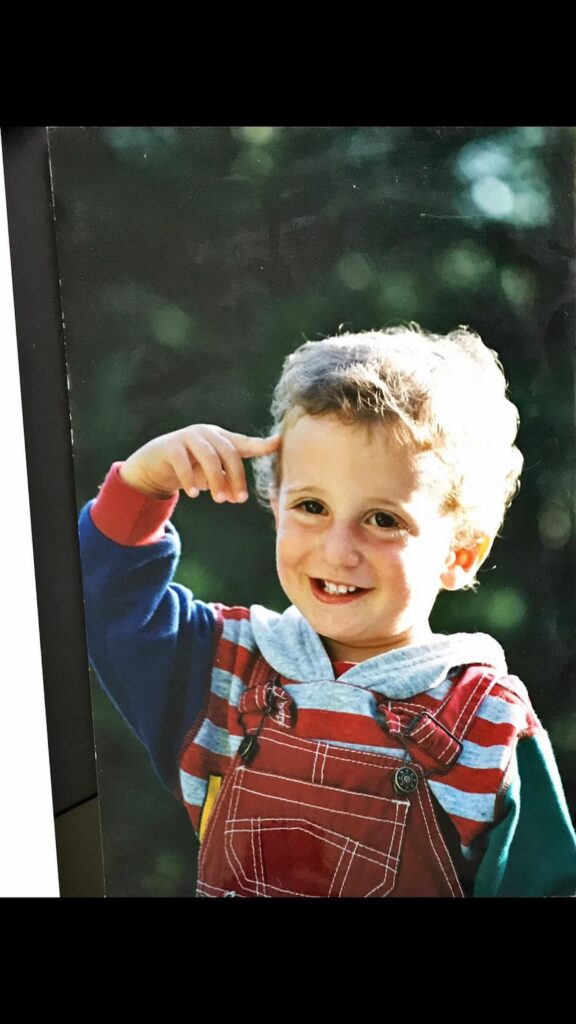

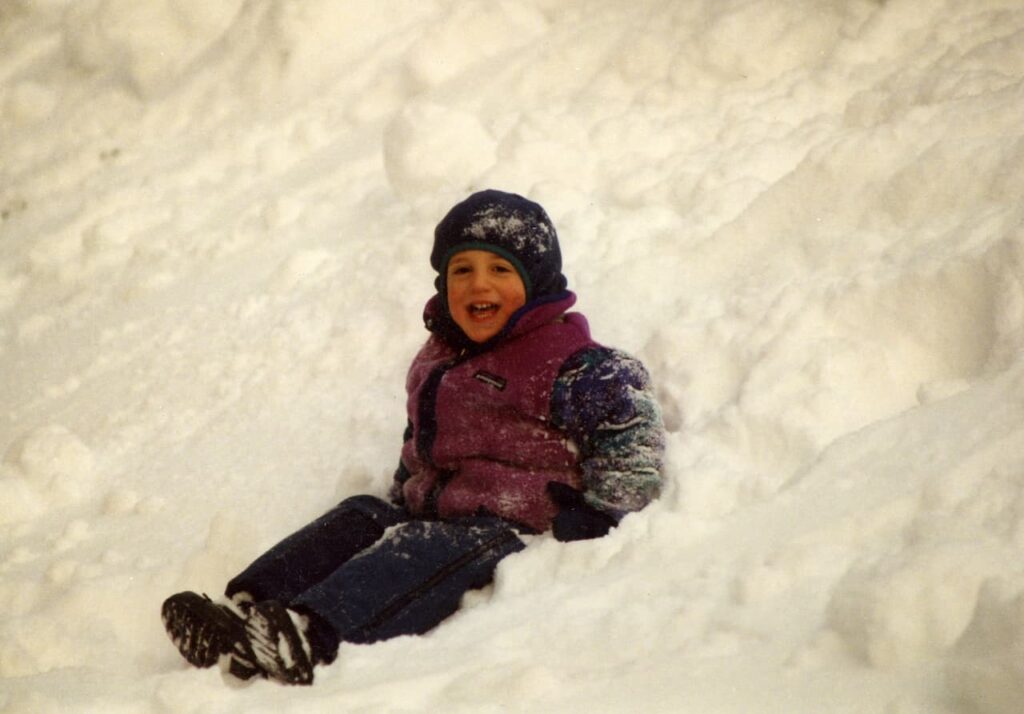

Pablito was an inventive child, who spoke a lot and was very active. His intellectual prowess, which would later result in him attending Oxford and London School of Economics, was already evident when he was a very small child. He had many questions for us and was incredibly alert. You would be exhausted after a day with Pablito, and I absolutely loved it.

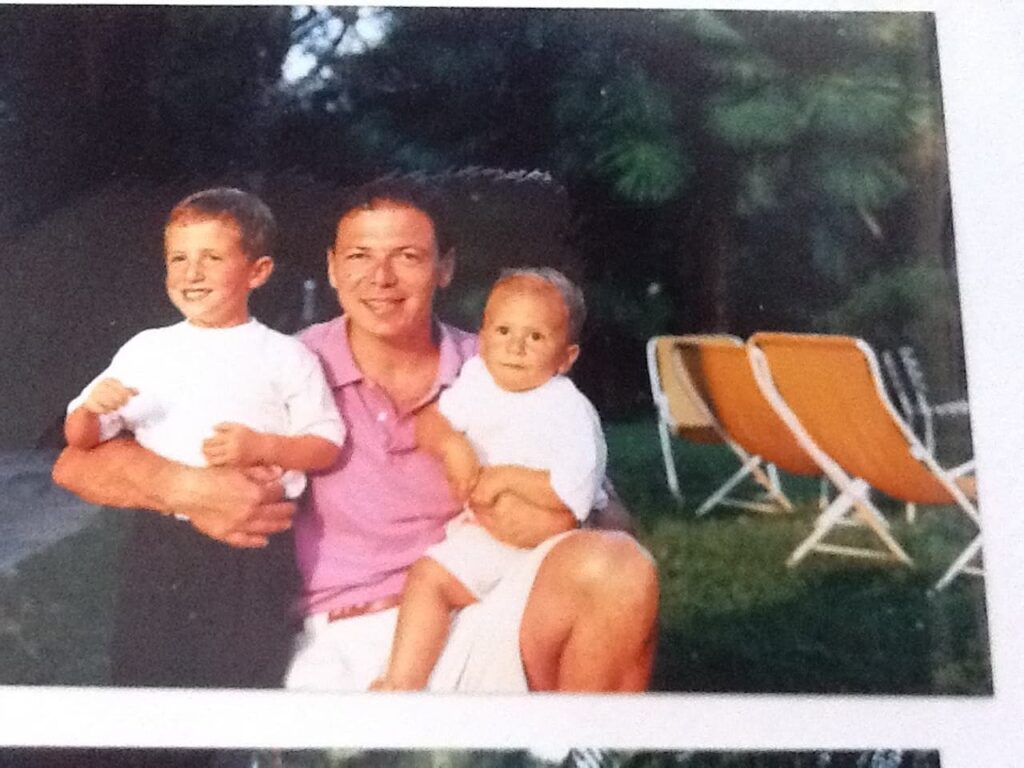

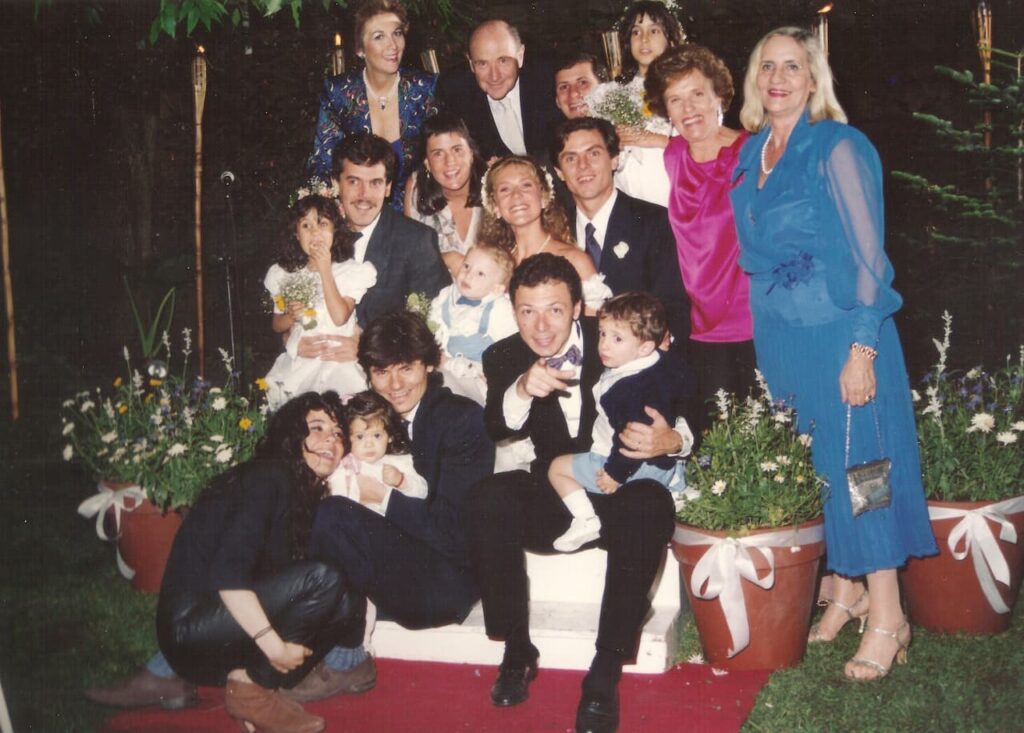

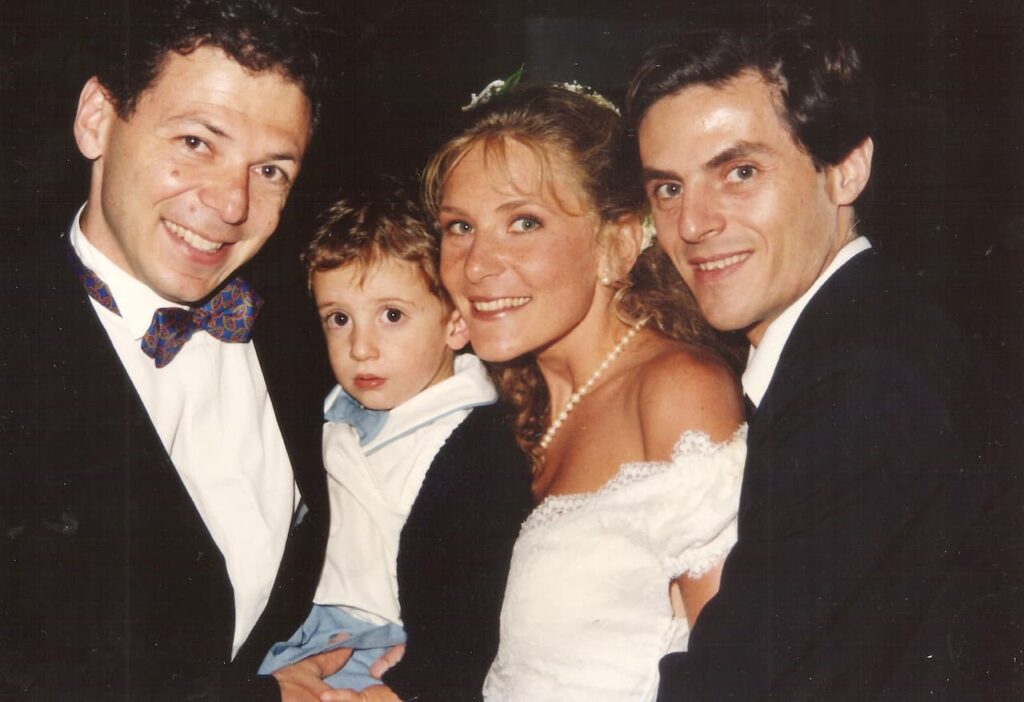

In 1993, my sister Sonia got married. I seized the occasion to travel with Pablito to Buenos Aires. Pregnant with Nico, Josée wasn’t able to join us.

Before leaving for Buenos Aires, Pablito had been an unusual child—he ate mostly vegetables and fruit, and practically no sweets. All of that changed during his first trip to Argentina. He and his cousin Axel were only two months apart, and hit it off immediately. They would climb their way to the top of Pato and Edi’s counter, and from there reach out to the container holding Sugus candies, which they would devour for hours. The rest of the day, they ate pastries and drank Coca Cola. Pablito had quite a cheeky personality and behaved in ways that made everyone laugh.

On the way back from Argentina, the flight was delayed and I thought it would be wise to hydrate Pablito. I filled his baby bottle with Coca Cola, something I knew he would not have access to in Geneva. He had one Coke, then another and by the time I picked him up to carry him on to the plane, I sensed a bit of wet. I checked and he was soaked, from head to toes. Despite Josée’s admonition, I had taken no extra clothes with me.

As a Daddy in charge of a small child, I boarded the plane first, and when I arrived at my seat, the smell of urine was all-pervasive. The friendly steward initially looked concerned, but then had an idea: ‘Quick,’ he said, before the other passengers enter the aircraft, ‘give me your child’s clothes.’ We undressed Pablito and he spent the flight from Buenos Aires to Rio wrapped in a large blanket. The steward put the wet clothes at the bottom of the first-class wardrobe and returned them to me just before we landed—the low humidity of the flight had dried them. On the way out, I heard several first-class passengers comment on how poorly the toilets were cleaned, and how you could smell piss everywhere on the flight. Back in Geneva, Josée also commented something about piss, but I quickly changed the subject, and it was only much later that she found out what had happened. As for Pablito, he had a lovely flight!

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko