It was during our time in Neuchâtel that we went on a two-week visit of North Yemen (at the time, it was a still a country split in two, and you couldn’t visit the South, which was in the hands of a communist regime). Visiting Yemen was like going back to the Middle Ages. There were practically no roads and almost everyone wore traditional garments. I was fascinated by the diversity of this nation, which had once been very rich and was, together with Oman, the only country in the Arabian peninsula that had a sustainable agriculture. Getting to Sana’a, the capital, was not easy, and we joined a group of travellers in Paris.

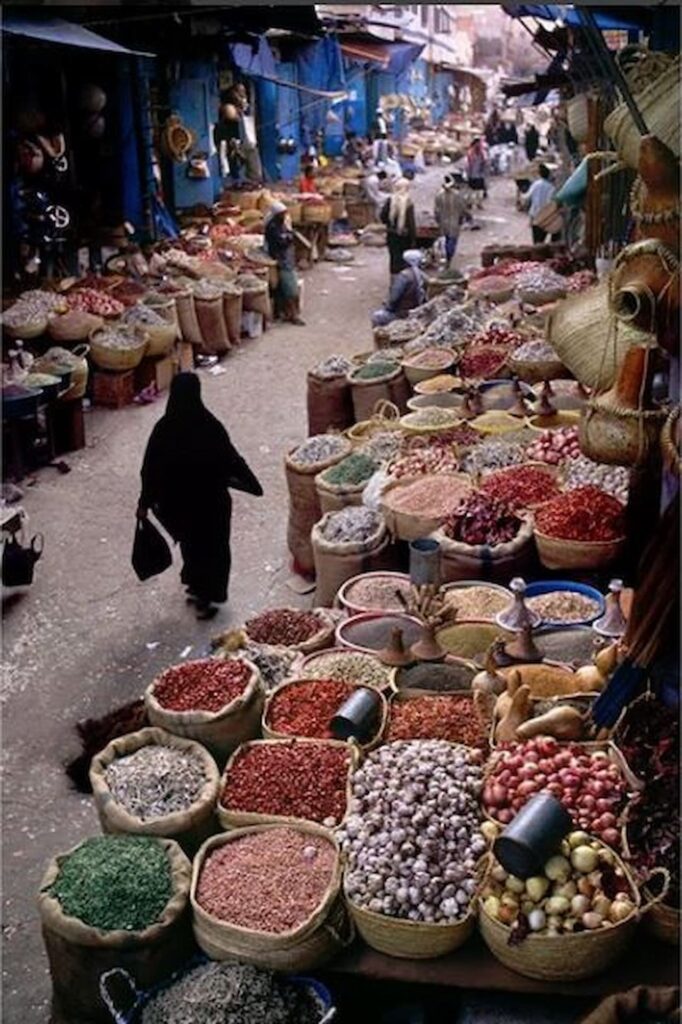

Once you got to Yemen, the experience was unforgettable: Sana’a was like a jewel, with hundreds and hundreds of beautifully preserved old buildings. The seaside town of Hodeida, where we slept in hammocks (since there was no hotel), gave you the feeling of what travel and trade must have been like in the Middle Ages, while Taez, nestled in the mountains, featured rich markets and a splendid selection of spices. The Yemenis were incredibly warm and friendly and the food was varied and delicious.

It was fortunate that we visited the country in the middle of Ramadan. I was struck by the discipline of the people. At about 5pm the Yemenis would start to congregate in plazas and cafés, would order something to eat or drink, then patiently wait. The second that the muezzins announced the end of the fast from loudspeakers installed all over the major cities, thousands and thousands of Yemenites started eating and drinking in perfect unison. Then the towns would come to life, there was singing and dancing on the streets. It seemed to me that everyone knew each other in Yemen. They did, but the nation operated in clans, which would later lead to an unending civil war and enormous suffering. But in 1989, Yemen was still at peace, and provided for indelible souvenirs.

During my second year at Jacobs Suchard, a number of headhunters started to call me. Mostly I declined invitations for interviews, but one day I was asked whether I would meet the European President of Pizza Hut. The fast-food chain was looking for a Head of Marketing for Europe. I hesitated, but eventually agreed to see them in London. The interviews went very well and a few days later I was asked to fly to New York to meet Wayne Calloway, at the time global CEO of Pepsico, the parent company of Pizza Hut.

Calloway was one of America’s most emblematic and influential managers of the 1980s. Apart from being Pepsico’s CEO, he was also a board member of Exxon, General Electric and Citicorp. A tall man, with a strong southern accent, he received me smoking a cigar. We spoke about Pizza Hut for a while, and he highlighted the many opportunities for the chain of restaurants in Europe. Before I left, he put his arm around my shoulder and, while we were both looking at the amazing New York skyline from his office, he said: ‘You know, if you do your marketing job well at Pizza Hut in Europe, in three years you’ll be here with me in New York, running one of our global businesses. And then, who knows, maybe one day you’ll replace me at the head of Pepsico.’

I flew back to Switzerland that evening, thinking: I don’t want to do this. I don’t want to move to London. I don’t want to sell frozen pizzas to people in Finland. I don’t want to find ways reduce the cheese content of Jalapeño Poppers in order to increase their margin. I don’t want to invent combo promotions to induce adolescents to consume more Pepsi, and I just cannot imagine sitting in meetings over the next three years tasting onion rings and Southern Fried Nuggets.

And, I thought, imagine if you go through all of this and you do your job really well, then the prize you win is to have this loud-voiced American as your boss. You can then have the privilege of living in this huge, noisy American city, overseeing some other type of hyper-processed snack business. After three years in London, I said to myself, you’ll be selling Doritos or Frito Lay or Matador Meat Snacks or Munchies Cheese Fix around the globe. And then, after that, only maybe and if I was a true star, then I would get to sit in Mr. Calloway’s big chair, overlooking the New York skyline and commandeering even larger groups of people, and being rewarded with millions of dollars by the Board if I succeeded in selling even more sugar and processed snacks around the world.

No, I didn’t want that. I enjoyed the mountains in Chamonix, barbecues with friends and hiking in the mountains. I thought that going for a run in the morning was one of life’s greatest pleasures and that reading Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain was what made life worth living. And I thought that being in bed at 10pm was worth a lot more than a big salary.

When I arrived in Colombier, I hardly had time to tell Josée about my experience in New York, when the phone rang. It was Klaus Jacobs. He was calling to personally give me ‘great news’. The board of Jacobs Suchard had just decided to appoint me CEO of Jacobs Suchard, Mexico. ‘A huge opportunity,’ Klaus said. ‘Our Mexico business is poised for enormous growth over the coming years,’ he confided. And yes, he added, in a few years, it was the Americas that I would be in charge of, including the Brach’s candy business which he had just been acquired in the US, and which required rapid regional expansion. And then, he said, after that ‘the world is open for you’, and I could definitely see you here with me in Zurich. I was dumbfounded, but managed to say ‘Thank you Klaus for the heads up’, and hung up.

Another one, I thought. That’s two of these guys in just 24 hours. And all I want to do is to drive to Chamonix and go for a hike to the Lac Blanc.

It was clear by now that if I let the headhunters or the Klaus Jacobs of the world manage my future, then I would be shoved from one country to the next, from one ‘exciting business opportunity’ to an even more ‘amazing’ one and that my career would be considered a smash hit if I sat in a big office overlooking the New York skyline (or perhaps a slightly smaller one overlooking the Limmat).

It was by now obvious: I was not made for a ‘corporate career’. I explained this to the Pizza Hut headhunter, who had begun to call me at all hours of the day and night, sharing with me ‘in confidence’ the magnificent impression that I had left on Mr. Calloway, a man who, you know, doesn’t see just anyone and who is one of those people that once they take you under their wing, will propel you to the very top. ‘Just think of Mr. Calloway’s contacts, Pedro. I mean, how old are you now? Aha, yes, just 31. Well, you just do this job for a while and you’ll see, the world will be talking about you. What an opportunity, dear Pedro, a very, very rare one, don’t throw it away.’

But I did unceremoniously ‘throw away’ the Pizza Hut opportunity, and two subsequent job offers that came on the heels of it. I also politely explained to Klaus Jacobs that it was too early for me to move to Mexico. And I got seriously thinking about how to exit the ‘corporate world’, and start doing something where I, and only I, would decide where, what and when things would happen in my professional life.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko