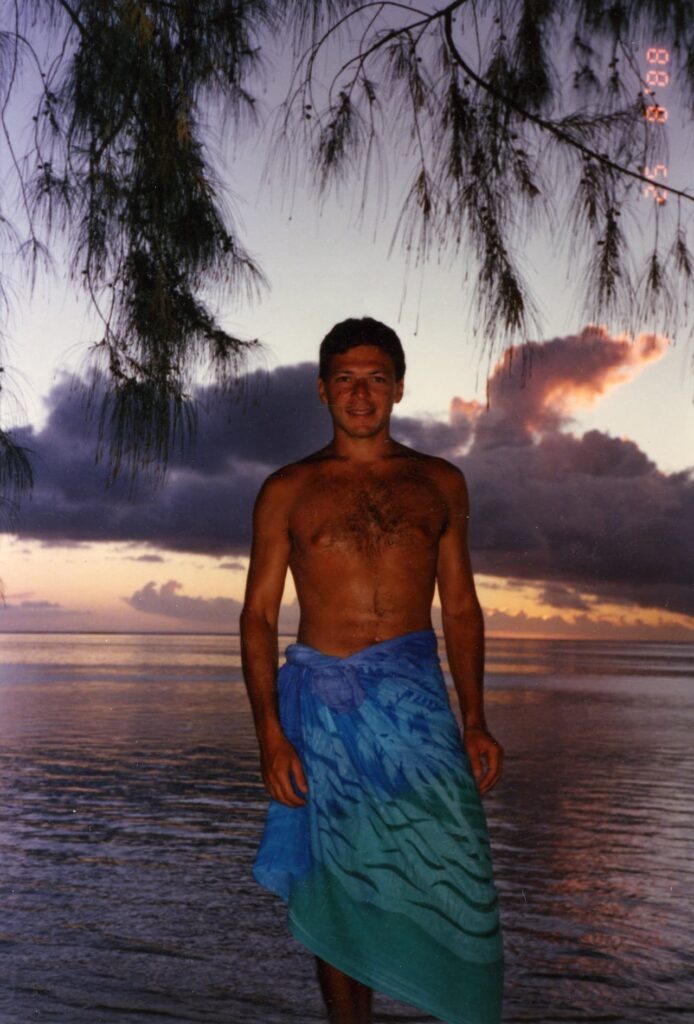

During the summer of 1988, Josée and I took a longer break. She had also obtained a job at Jacobs Suchard. We both moved our starting dates to September, and spent the summer in Chamonix, Canada and Tahiti. It was a beautiful time. Neither of us had any constraints, we had great jobs to look forward to, and we had saved enough money in the UK to allow us to enjoy our free time to the fullest.

We had originally intended to stay in Geneva and commute to Neuchâtel, where we both would have our offices. It was tempting to do so, since our apartment in Geneva was only a few minutes’ walk from the train station and a one-hour commute didn’t sound like much, but Nico Issenmann convinced us that it would be better for us to be based in Neuchâtel.

So, we packed our bags once again and after a short search, found a delightful lodging in Colombier, only a few minutes’ drive from the Jacobs Suchard offices in Serrières. Our large apartment was located in what had been the home of Madame de Charrière, an eminent XVIIIth century literary and enlightenment figure. It was a beautiful place, full of history and intriguing stories (we lived in what had been Madame de Charrière’s personal rooms; they included a secret staircase which, apparently, her lovers would use).

Jacobs Suchard was a cultural shock for me. P&G was a data-driven company, with very clear procedures for everything and long evaluations before action was taken. There were no systems at Jacobs Suchard, decisions were made ad hoc, on the spur of the moment! If Klaus Jacobs liked an idea you had, he would build three factories immediately, without any lengthy analyses. I had 15 people in my marketing team, which was enormous for the size of Switzerland. Nearly all were from the Neuchâtel region, and had been in the company for many years.

At lunchtime, for about two hours, the company was deserted—employees went home to have a leisurely meal and many had a nap before returning to work. In the winter, lunchtime breaks were a bit longer, with many on my staff leaving early for cross-country skiing, but they of course insisted on having a warm meal before returning to work. People arrived early, at about 8am, but the company was deserted by 5pm. Very few on my staff ever left the office to see what was happening in the stores, and none had a clue about what consumers thought and felt about the brands they were selling. My marketing team didn’t concentrate on consumers, they focused on the needs of the Jacobs Suchard factory, which in turn received its orders from the sales team, who got precise requirements from the key supermarket chains (mainly Coop and Denner).

Three days after my arrival, I received a letter from Nestlé, our key competitor, signed by the Swiss Marketing Director. In it, he warmly welcomed me to ‘the Swiss chocolate team’ and said that he looked forward to seeing me soon at the Chocosuisse meetings. There was one issue, however, that couldn’t wait. Nestlé wanted to launch a new chocolate bar and he wanted my approval before going ahead.

I read the letter three times, then went to see my boss. ‘This must be a joke,’ I said. At P&G, we had had zero contact with competitors and kept our marketing plans totally secret. In fact, we didn’t even know the names of those who worked at Unilever or Henkel, and had no idea where their offices were located.

‘It isn’t a joke,’ Nico Issenmann said, ‘it’s the way things are done in Switzerland.’ He then explained that since the 1940s, most Swiss industries (including chocolate) had been cartelised, with all major manufacturers getting together regularly and agreeing common commercial terms, including prices. This had originally been set up to ensure smooth production during the wartime period, but had been kept ever since, because it was very convenient for the manufacturers, especially the largest ones like Jacobs Suchard and Nestlé—it allowed them to keep prices high and limit competition from new entrants.

The chocolate manufacturers’ cartel was called Chocosuisse and its members got together regularly to agree common business terms, which, in good Swiss fashion, everyone strictly adhered to. ‘What about Nestlé’s chocolate bar launch?’ I asked. ‘Ah,’ said Issenmann, ‘as a matter of courtesy, we regularly exchange information on our major product launches. It’s a way to ensure that we don’t crowd the field with too many similar products, which would allow the supermarkets to pitch one manufacturer against the other.’ ‘So, what do you want me to do with the Nestlé guy’s letter?’ I asked. ‘Well, just tell him it’s OK to go ahead. We launched a new chocolate tablet last month and they said yes, so we should do the same,’ he said.

So that was how things were done in Switzerland. You got chummy, chummy with your competitors and arranged things in a way that kept everyone happy. As a large manufacturer, what you didn’t want were newcomers or fights with your competitors. Switzerland would slowly emerge from this medieval way of doing business, but that only happened later, in the 1990s. In 1988, the premise was: be friendly to your competitors and don’t rock the boat.

I was accustomed to P&G’s intensive and stressful environment. Jacobs Suchard felt like a holiday. After a while I realised that it made no sense to push for too much change too quickly, and I did what everyone else did: enjoy my time. Klaus Jacobs himself believed in a healthy work-life balance. Accordingly, all offices worldwide were closed early on Fridays, to ensure that employees could have a full and restful weekend. So Josée and I would leave the office punctually every Friday at 3pm and head to Chamonix, where we arrived no later than 5pm, returning on Sunday evening.

Jacobs Suchard considered that team building workshops were essential to stimulate morale, and that getting to know oneself and the others better was critical to business success. Accordingly, several times a year, off-site sessions were organised, many of which took place in Schloss Marbach on Lake Konstanz, a magnificent property that Klaus Jacobs had bought for the sole purpose of providing an appropriate setting for training sessions.

Business life at Jacobs Suchard ran in Helvetic tempo, with everyone having plenty of time for everything, and with lots of attention being placed on formalities and, especially, politeness. If you disagreed with someone, you wouldn’t say it upfront, like at P&G. That was considered bad manners. You would beat around the bush, then perhaps make a comment after the meeting and look for a way to find a solution where the person in question would not lose face. It was better to not make a decision, or even to make a bad decision, than to make one of your colleagues ‘look bad’ or feel uncomfortable. Collegiality was the name of the game. And democracy, of course—everyone needed to have their say and you wouldn’t have wanted a meeting to end without all voices being heard.

It didn’t take me long to realise that Jacobs Suchard would not be the place where I would end my career, but I took my time before thinking of my next move. I was happy with our weekends in Chamonix, happy with our home in Colombier and happy with the time Josée and I were spending together outside work. Neuchâtel was a sleepy town, but I was never one to stay up late or go out much. In the time before mobile phones and the internet, when you left the office, you were really gone, so I enjoyed the quiet evenings reading books, listening to music and cooking. Josée and I also made some friends locally, and we often organised dinner parties during the week.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko