In the autumn of 1986, P&G announced to me that they wished to transfer me to the UK. Ron Pearce, one of the Geneva General Managers had moved there a year before, and suggested that I take over Ariel Liquid, a brand that was about to be launched in the UK. Josée, who had recently joined P&G in Geneva, was offered a position in the Promotions Department. We accepted and were the first dual-career couple ever to be jointly transferred within P&G.

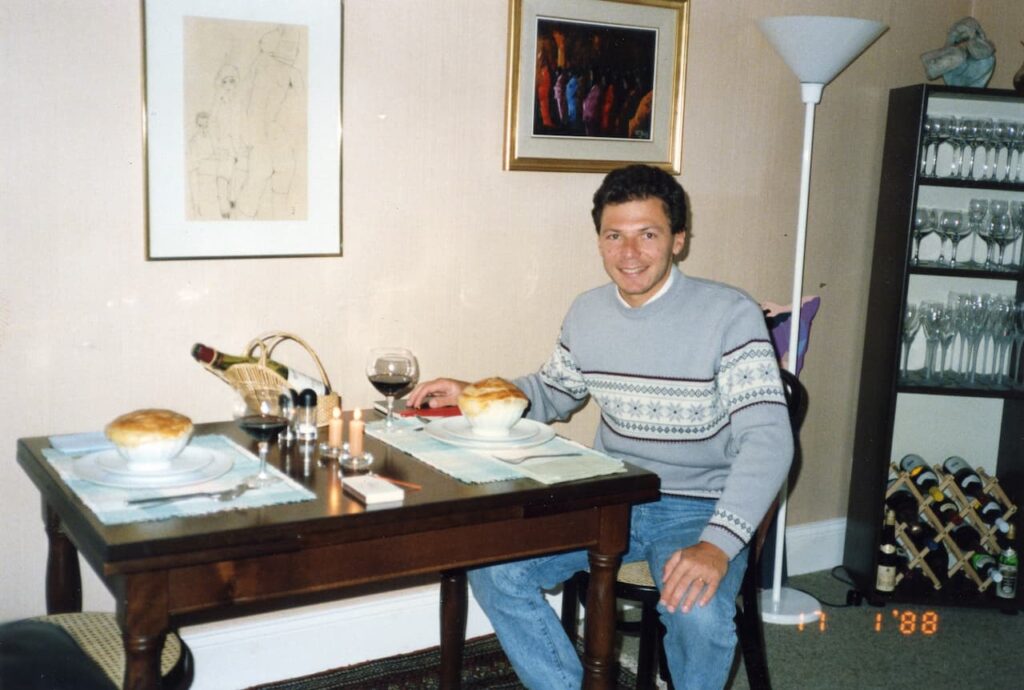

It was difficult to find a suitable place to stay in the area of Newcastle, where P&G’s UK office was located. Almost everyone in the area bought property, something we did not wish to do, since our intention was, after a stay of one or two years, to return to Geneva. After months of fruitless searching, we finally found what we thought might be a suitable place—the wing of a castle, which had been refurbished into a one-bedroom apartment. I went to see the place and found it stunningly beautiful. At £ 35 per week, it was also more than reasonable. It only had one problem: there was no shower, only a bathtub. I asked Josée what she thought, and we agreed that if the British survived without showers, so would we!

So, we moved into ‘The Brewhouse’, at Halton Castle, located in the middle of England’s beautiful countryside, between Corbridge and Hexham, about a 30-minute drive from P&G’s office in Gosforth, Newcastle.

Our time in Halton was to become one of the most memorable of our lives. The main building was inhabited by Sir Hugh and Lady Anna Blackett. The Blacketts were baronets, who had obtained their title in the XVIIth century and lived at Halton Castle ever since. The castle itself had been built in the XIIIth century with the stones from the wall that the Roman Emperor Hadrian had built at the beginning of the second century AD. The original castle had had four towers, but only one survived the many architectural changes over the following centuries.

Hugh and Anna were only a few years older than us and gradually opened up to these strange people from Switzerland who were staying in what had been intended as a lodging for Hugh’s father, who had unexpectedly decided to remarry and had instead moved into his wife’s home nearby.

On one of the first days after our arrival, I knocked on the door of the castle. Anna opened and I asked: ‘I’d like to know how to take a bath.’ ‘A bath?’ she said. ‘Yes, a bath. We’re not accustomed to taking baths.’ ‘You mean that you’ve never washed yourselves?’ asked the horrified Anna who, as a precaution against possible emanation of undesirable odours from the foreigner in front of her, had moved back a few steps.

‘Oh no,’ I reassured her, ‘we wash ourselves every day. We take showers, but we’ve never taken a bath before.’ Visibly reassured, she said: ‘All you have to do is to is pour hot water into the bathtub and sit in it.’ ‘Yes, but what about the soap?’ I asked. ‘What about it?’ she said, ‘don’t you have soap in your country?’ ‘Yes we do,’ I said, ‘but what do we do after we’ve soaped ourselves up?’ ‘What do you mean?’ she said. ‘What do we do after we’ve put the soap on?’ I wanted to know. ‘Well,’ the puzzled Anna said, ‘you just submerge yourself under the water.’ ‘And then what?’ I asked. ‘Then you get out and dry yourself.’ ‘But then we’ll still be full of soap and so will our towels,’ I said. Anna thought about this for a moment and then said: ‘Well then, I guess that we’ve been soapy in Britain for at least the last 500 years.’ And so it happened that Josée and I learned to be soapy for the years we lived in Britain.

A few days later, Hugh knocked on our door. He wanted to introduce himself. Josée opened and in her strong French accent said: ‘Ellô, I’m Josée, what is your neim?’ ‘Hugh,’ said the man at the door, which Josée decoded as ‘You’. ‘I’m Josée,’ she repeated with a big smile and stretching out her hand, ‘please tell me what your name is.’ ‘Hugh!’ said the very polite and soft-mannered Hugh, this time slightly more forcefully. At this point Josée got impatient and said: ‘I already told you what my name was, please now you tell me what yours is!’ ‘Hiou,’ the man at the door said. ‘Ah,’ said a greatly relieved Josée, ‘Hugues, what a nice name, please come in!’ So Hugh, after having been renamed ‘You’ for a few moments, finally became ‘Hughes’, a posh and convenient name, which fitted Josée’s perception of who she had in front of her.

The following Sunday, Josée bumped into Hugh, who was walking his dogs. ‘Hello Josée,’ Hugh said. ‘Êllo Hughes, ôw are iou?’ she responded. ‘Very well,’ Hugh said. ‘How are you settling in?’ he wanted to know, ‘is your Aga working well?’ ‘Oh yes,’ Josée said, ‘we had a great dinner last night!’ ‘What did you have?’ Hugh wanted to know. Joseé tried to say that we had had duck, but out of her mouth came the word ‘douck’. Hugh, who thought he had heard ‘dog’, said: ‘Aha, and what…kind…of…dog meat would this have been?’ ‘Oh,’ Josée said with a smile, ‘it was a local douck, we got a very nice piece from a big animal.’

Hugh started to count his labradors to make sure they were all there. He then asked: ‘And where did you get this dog meat from?’ ‘It wasn’t easy,’ Josée confided, ‘they don’t sell douck meat everywhere, we were told by a Chinese friend where to go. It was delicious,’ she said. ‘We still have some, would you and Anna like to try it?’ By this time, Hugh had completely freaked out, said goodbye and we didn’t see the Blacketts for a while. It was only months later that I solved the mystery about our ‘douck’ dinner, to the great relief of Anna and Hugh.

We only gradually became acclimatised to the British way of life, but not without committing a whole series of gaffes. On one occasion, it must have been two or three months after moving in, Anna invited us ‘for drinks’. ‘Thank you,’ I said, ‘at what time should we come?’ ‘Come at 6pm,’ she said. Josée and I wondered what an invitation to ‘drinks’ meant. We had only ever seen the Blacketts wandering around their property, dressed in dilapidated green Barbours and Wellington boots. They looked like beggars (I had once asked Anna how you cleaned a Barbour. She had laughed and said: ‘Pedro, you don’t clean Barbours!’).

To play it safe, and in order not to embarrass our landlords, we decided to dress in very clean jeans, white shirts and V-neck pullovers. In order not to appear as over-eager, we also decided to arrive half an hour later than Anna had indicated.

When we entered the Blackett’s home, we were flabbergasted. There were dozens of couples there, who had visibly all arrived on time; we were by far the latest. Everyone was exquisitely dressed, the men in wonderfully tailored suits of the finest quality and the ladies wearing gorgeous jewellery. ‘Would you like a drink?’ I heard someone say. It was Hugh, who I could barely recognise, dressed in a perfectly tailored suit. Anna was unrecognisable too. She was wearing a beautiful pink dress, diamond earrings and an exquisite collar of pearls. It was we who felt like beggars!

The Blacketts introduced us as ‘our friends from Switzerland’. People were friendly, but we felt completely out of place. I had one drink, then another and by the time the third drink arrived, I wondered where the food was. I was getting a bit tipsy and was looking for something to eat, but there was absolutely nothing, not even a few peanuts.

At about 7.30pm, suddenly all the guests got up and left. It all happened within a few seconds. Now it was just Hugh, Anna and us in the large living room. We continued to talk with them for a while, until it became obvious that they were feeling uncomfortable and, to my dismay, it was now very clear that no food would be forthcoming. So Josée and I left. We had no food at home, thinking that we would be eating at the Blacketts, so our evening ended at the local pub, eating fish and chips, served on newspapers. The evening had taught us a few important things: when the Brits say ‘drinks’, they mean drinks, that’s it. You better show up on time. And: don’t get deluded by what people look like during the day, the Brits can look very different in the evening or when the occasion asks for it!

On another occasion, we were invited to tea by Derek and Maureen, our next-door neighbours. Apart from the castle, the Blackett estate included about five or six stone ‘cottages’, where people who worked on the estate were lodged. Maureen and Derek occupied the cottage closest to us—he worked as a handyman and Maureen was hired as a cleaning lady.

We had been a few times at the Blackett’s for tea. For us, it had been a familiar event—a small meal served at about 4pm, which included scones, cakes and marmalades of various types, accompanied by Earl Grey tea, served with a bit of milk.

On the agreed day, when we showed up at Derek and Maureen’s at 4pm, there was no one there, and the door was locked. We waited for a few minutes, then returned home. At about 6pm, a worried Maureen rang our doorbell. She wanted to know if we’d forgotten about tea at her place. ‘Oh no,’ we said, ‘we haven’t, we came to see you, but the door was locked!’ Puzzled, Maureen asked us at what time we had showed up. When we told her, she said: ‘That was much too early, we have tea at 5.30pm!’

So off we trotted to Maureen and Derek’s place, where a full buffet was laid out on the table. There were salads of various types, steaming hot potatoes, smoked fish and a selection of hot and cold sausages. There was also beer served. After a copious meal, at about 7.30pm, Derek said: ‘Let’s go to the pub!’ So off we went to The Golden Lion, where we drank an additional pint and played darts until about 10pm.

So now we knew: ‘tea’ in England means different things to different people—you better ascertain which social class is inviting you before you show up!

Over time, and after it became clear that we were to be trusted, we began to see more and more of the Blacketts. They and their friends gave us a unique insight into the lifestyle of the British landed aristocracy. During the winter months, we frequently accompanied them on shooting trips, some of which took place on their own grounds. Other activities included horse races, called ‘point to point’. By then we had bought Barbours and Wellington boots and began to look like everyone else in Northumberland. The Blackett’s friends, who all lived on similar properties as they did, had exactly the same English accent, even though their homes were in completely different parts of Britain. This, we were told, had to do with the schools they attended.

Not all our weekends during our time in England were spent in the countryside. We often went to London. I tried to organise meetings with the agency on Fridays, Josée would join me at the end of the day, and we would spend the weekend watching plays, visiting London’s many interesting sites and eating dumplings in Chinatown.

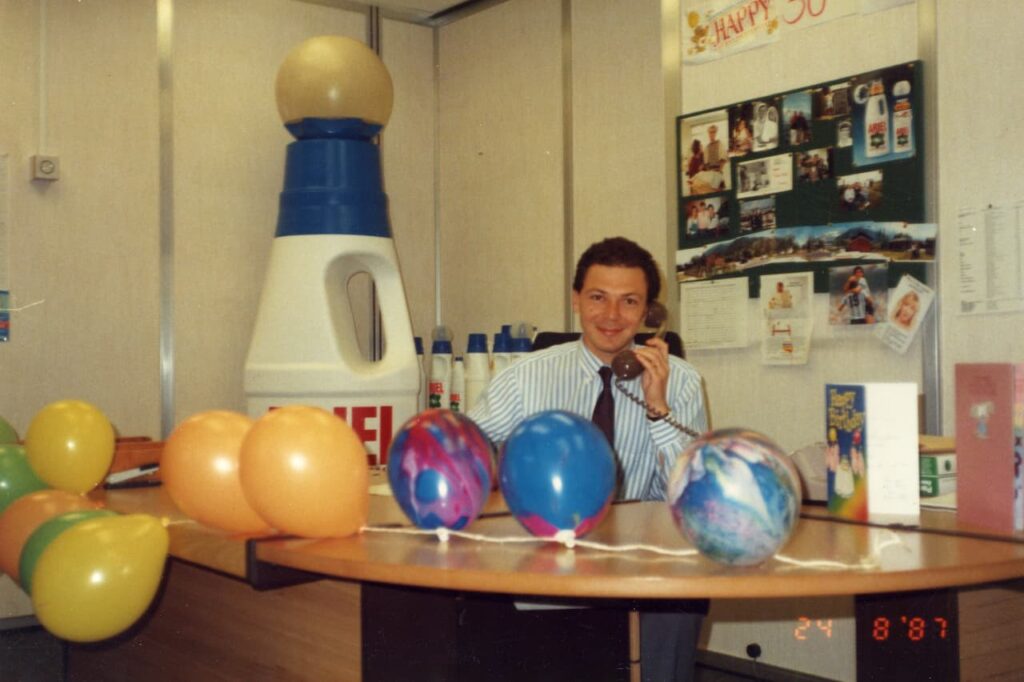

At work, I was put in charge of Ariel Liquid, the biggest laundry detergent launch that P&G UK had had in decades. Ariel Powder was the best known brand in the UK, but habits were changing and more and more Brits were preferring liquid detergents. P&G had introduced Ariel Liquid a few years before, but it hadn’t been a big success. Consumers poured the liquid into the same compartment as the powder, with the consequence that by the time they turned on the machine a few seconds later, most of the liquid had gone down the drain and the machine washed with only a little liquid detergent, with very poor results. Consumers logically concluded that Ariel Liquid was no good.

P&G had solved the problem by putting on the market a new bottle, which included a plastic ball, called ‘Arielette’. You now poured the liquid into the little ball and placed it into the laundry directly. It was a revolution in consumer habits and it required a totally new advertising campaign. Saatchi & Saatchi, in charge of Ariel’s account, came up with a memorable TV ad, the ‘Mother in Law’ campaign. I arrived just in time to choose the winning storyboard, which was produced during the first weeks after my arrival.

We supplemented the launch by setting up an unusual in-the-field product sampling campaign with washing machine manufacturers. At the time, P&G paid quite large sums of money to several washing machine manufacturers, such as Zanussi, Bosch, Hoover, Indesit, etc. In return, the manufacturers would ‘endorse’ Ariel and, crucially, include a small box of Ariel Powder with every new machine delivered. This had worked extremely well. I tried to have Ariel Powder replaced by Ariel Liquid, but of course my colleagues who ran Ariel Powder would not agree.

By looking at the detailed reports that we received from manufacturers, I realised that, at the time, washing machines broke down quite frequently, requiring literally thousands of repairs each month across the UK. Machines that didn’t work, even for a few days, created havoc for consumers, particularly in large working-class families, where a lot of clothes were washed almost daily. Desperate mothers, who needed to get their family’s clothes washed, needed to resort to handwashing until the repairman showed up. When he did, invariably later than when the machine owners desired, he faced very upset people, desperate to get their machine fixed. While the man worked on the machine, the anxious mother would stand around and often get in the way of the man’s work. So, I had the idea of offering each repairman little boxes with filled Arielettes. Each box included a detailed description, not only on how to properly dose the Arielette, but also how to prewash with liquid detergents, thereby helping to remove particularly difficult stains. It would have been impossible to communicate to consumers such detailed information, and in the time before the internet, there was no other efficient way to reach them.

Repairmen began to distribute our sample kit and soon we were inundated with requests for more. The repairmen would send us pleading notes, asking us how many boxes we could send to them and by when. Some even showed up at our offices, so as to get their assignment of boxes quicker. The Arielette box had solved two problems for the repairmen: they kept the clients busy while they worked, and they allowed them to give the mothers ‘a present’ as soon as they arrived. This completely changed the atmosphere of the repairman’s daily rounds. For us, it meant that we had found a rapid way to sample consumers. Ariel Liquid entered consumers’ homes when they had the time to read about detergents. Importantly, the fact that the repairman brought along the sample personally, gave the brand an extraordinary implicit endorsement, something that no ad on TV could achieve.

Ariel Liquid took off like a rocket. It rapidly became the most successful laundry detergent launch that Europe had had in decades. At the time, P&G did not manage their brands centrally in Europe; every country did its own marketing, but a system of ‘European Brand Manager’ had been set up. The EBM had no formal power over his fellow brand managers, but he was looked up to, and was frequently solicited by his colleagues.

I was appointed Ariel Liquid EBM and had to organise European meetings. At the beginning, I enjoyed the travel and the responsibility, but soon I became disenchanted with what I experienced. The meetings were procedural, not business-focused. My colleagues, and especially their managers, were primarily interested in reproducing what we had done in the UK, without thinking through whether the same programs could work in their home countries. I often had to argue with other countries, to convince them not to use our ‘Mother-in-Law’ ad, a campaign that had extensive dialogues with British undertones, and included actors that were impossible to use in other countries.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko