I arrived in Geneva on August 25, 1982, a day after my 25th birthday. Waiting for me at the airport were John Langdell, my first boss at P&G and John Burke, who I had met during my interviews earlier in the year, and who would become a lifetime friend. John Burke and I are the only two from the initial group of P&Gers who would stay in Geneva for the rest of their lives, but I was unaware of this at the time.

John & John wished me a warm welcome to Geneva and to my job. I was over the moon to be settling in the city I had fallen in love with.

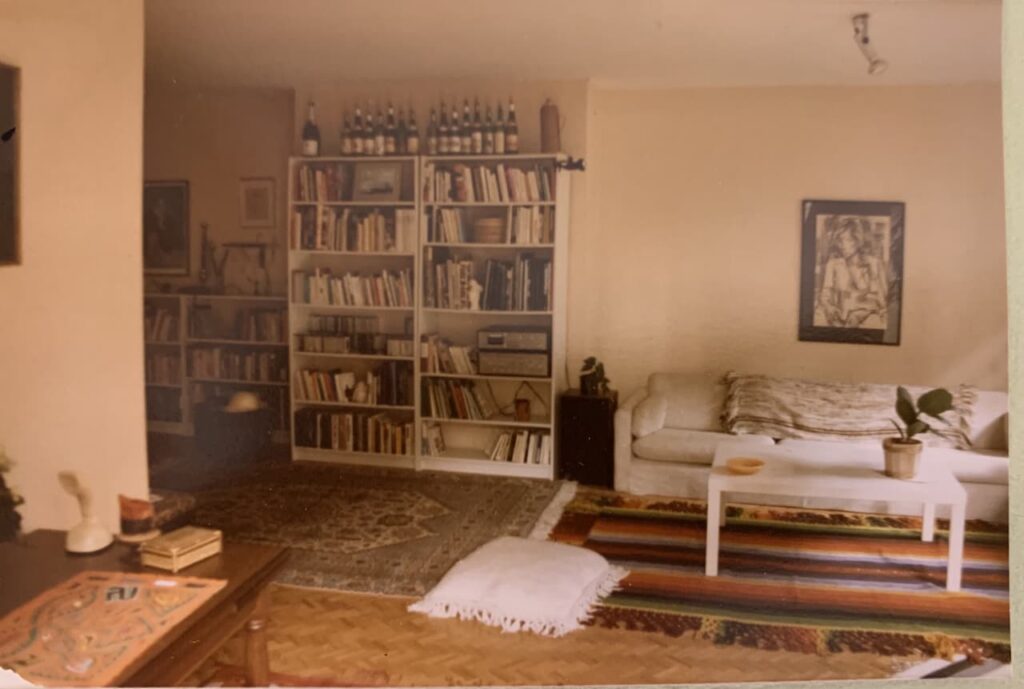

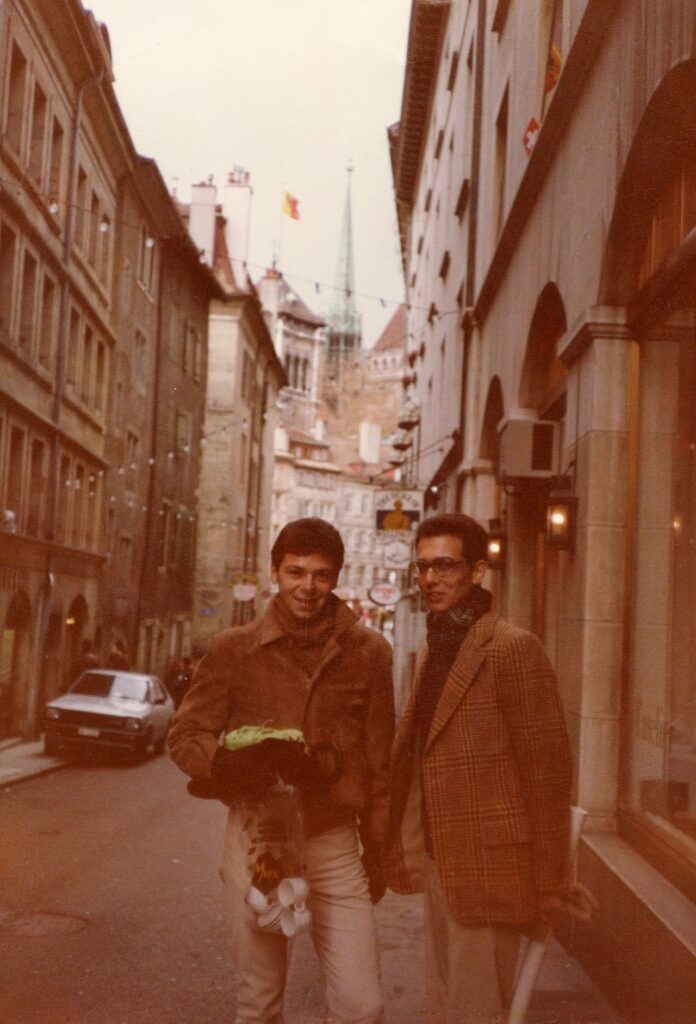

Through an extraordinary coincidence, my friend Fer, who had graduated from Harvard College the year before, was also starting a job at the University of Geneva, at exactly the same time as I arrived, so we decided to live together. We found a two-bed apartment at 2, rue de Neuchâtel, within walking distance of both our jobs.

My first salary at P&G was CHF 5,000 per month. After deductions for taxes, medical expenses and rent (for which Fer and I contributed in proportion of our salaries), car lease, as well as a loan I received from P&G allowing me to purchase furniture and other essentials, I was left with about CHF 700 per month to live on (the equivalent at the time of USD 350). It wasn’t much, but I was happy and eager to start my new life.

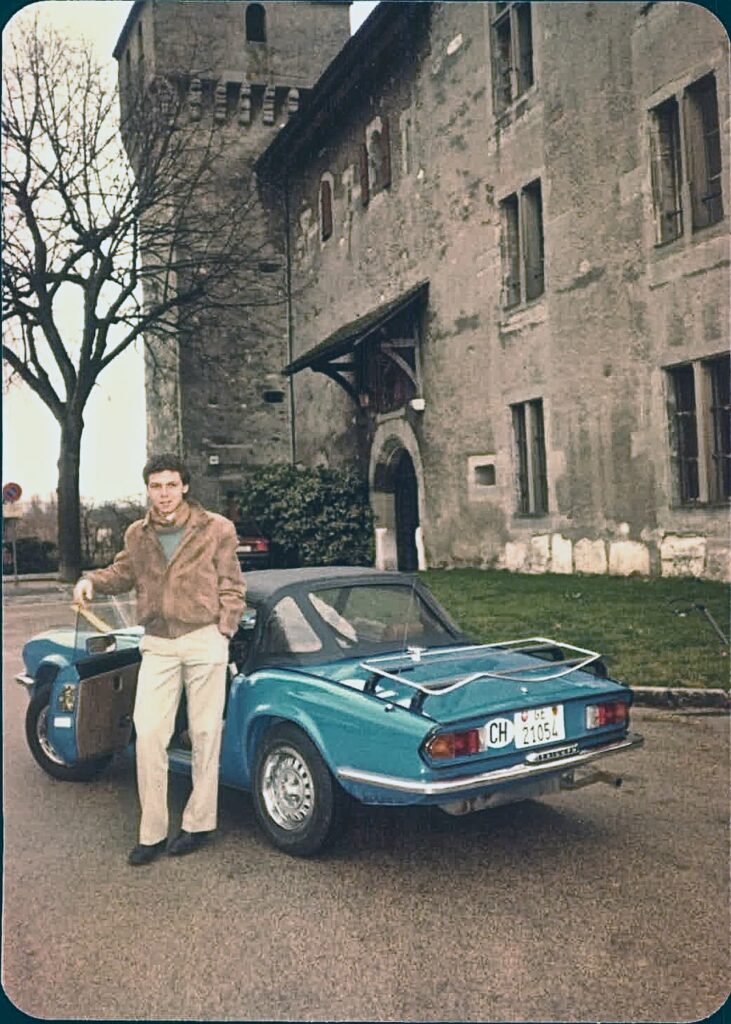

I purchased a second-hand blue 1978 Triumph Spitfire. It was a two-seater and often broke down, but on the days when it was sunny (and there were many), it was just heaven to drive it.

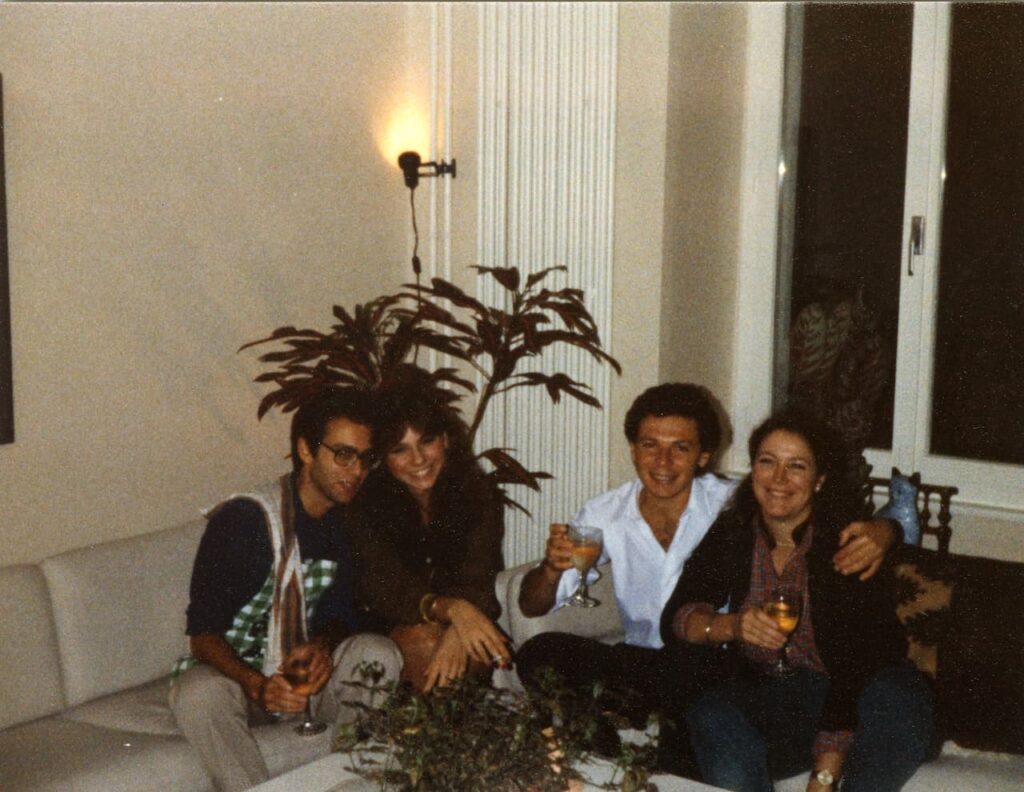

Our apartment, located only a few meters from the train station and less than five minutes’ walk from the lake, was perfectly located. Fer and I cooked with great passion and had people over for dinner very often. The weekends were filled with excursions to the mountains and with social events. We were rapidly surrounded by a large group of friends.

Most of the people working at P&G knew only expats, but thanks to Fer’s job at the university, our group of friends was very diverse, including many locals or people who had lived in Geneva for a long time. I spoke only rudimentary French, but set my heart on improving it rapidly. With no time or patience for courses, I made sure to read as often as I could in French, starting with the Tribune de Genève every morning. At work, all communication was normally in English, but my assistant was from France, so I tried to speak with her only in French. And of course, with Fer’s university friends, I had no option but to speak in French. It only took a few months before I was quite fluent in French.

My first assignment as a Brand Assistant in the Marketing Department of P&G’s Export and Special Operations Division (E&SO) was on Jordan. At the time, E&SO was in charge of P&G’s international expansion. Ed Artzt, who had recently been appointed Head of International by P&G’s board, who would later become the global CEO, and who I had met during my interviews, instigated a very ambitious international growth program. P&G’s Geneva office spearheaded the plan, and from 1982 onwards started to recruit a large group of recent university graduates like myself.

John Langdell was a good boss. He took his time to explain to me the rudiments of the business and how to handle the P&G culture. At the time, P&G behaved very much like a sect, with initiation rites including learning how to talk, how to write and how to behave in front of Management.

In the initial weeks following my arrival, I was asked to join a number of courses, including a two-day seminar called “How to write”. I told John that I preferred to stay in the office and work on our marketing plans for Jordan. I already know how to write in English, I said, ‘I wrote a 300-page thesis at Princeton!’ ‘I know you know how to write,’ John responded, ‘but you don’t know how to Procter-write.’

What John meant was that P&G used a particular vocabulary and a rigid structure for its internal communication, most of which revolved around ‘recommendations’. A P&G ‘reco’, as they were called, always began with ‘This is to recommend…’, which in one sentence summarised what you asked the company to approve. Memos were always addressed to your immediate boss. The next sentence indicated who was concurring with your decision (it wasn’t your boss, since you were writing to him; it referred to members of other departments, who had not only to say yes, but actually sign in the place where their names appeared, leading to sometimes extraordinarily long discussions about minor or irrelevant points concerning your proposal). This was followed by a background section and three (never two or four or five) reasons why you believed that your recommendation should be approved. All recos had to fit into one page, and finished with the same line: ‘May we have your agreement to proceed?’ ‘But it’s only me writing to you, why should I use “we”?’ I asked John. ‘We use the “royal we” at P&G, like the Queen,’ John (who was an Englishman) responded. Attachments were allowed, but the text of the reco had to fit into one page, and one page only.

It was a struggle to get sometimes very complex thoughts into one page and find three (and only three) reasons why your proposal made sense. In the time before PCs, recos were written by hand and then given to your secretary, whose main daily task was to type documents. It was difficult to know in advance how your handwritten text would translate into a typed document, so you would hope and pray that what you had written would somehow fit into a page. The secretaries would use hours and sometimes days to play with margins or change typefaces, to make your text fit. Or you just had to take out text, a major drama if you thought a certain point was essential to your reco.

Once you finished your reco, it went to your boss who would, of course, want to make changes before he sent it ‘up the line’. This would involve further drama with the secretaries, who were asked to take this paragraph out and replace it with this other one, etc. Sometimes secretaries who had been good in kindergarten, and had learned how to cut and paste creatively, would manufacture marvels by using scissors, a correction fluid with a little brush called Tipp-Ex, a paper glue stick and a photocopier. At times, so many secretaries were using the two available photocopier machines, that long lines formed, and you had to wait for hours before the changes that your boss wanted in your memo would revert to him.

Once your memo was OK’d by your boss, he would send it to his boss accompanied by a handwritten note, on which he added not just his approval, but an additional word of wisdom. It was therefore not uncommon for your boss to tell you to eliminate a certain message in your reco, because he wanted to make the point in his own cover note. Depending on the level of approvals required, your boss’s boss would then add another cover note to his boss, also accompanied by a relevant remark (otherwise, what was he there for?) and so on. For big decisions, like building a new factory or launching a new brand, it was not uncommon for your memo to return accompanied by 15 or more cover notes.

As you can imagine, reco writing was hardly a fast process and it could take weeks, if not months, between an agreement ‘in principle’ by Management and the actual ‘go ahead’, which could only happen when the signature of the appropriate hierarchical level had been obtained.

As a Brand Assistant, your days were filled with the management of recos which were at various stages of development. You were either running around gathering signatures from people who had to ‘concur’ (and who usually had to sign several times, as the same text kept being amended), or pleading with your secretary to make yet another change to the text which your boss suddenly thought of, or updating information, or answering a question from your boss’s boss about some issue you hadn’t covered in your text, but might be important to ‘get the reco through’ his own boss, etc.

You were measured on how many of your recos had ‘made it’ and how long the process had taken. On your desk there were no computers or other electronic artifacts, just two wooden boxes, both in A-4 size: on one was written in big letters ‘In’, on the other ‘Out’. Every now and again your secretary would show up with the ‘In’-tray and take out whatever was in the ‘Out’-tray. There were indeed magical moments in your day, when into the In-tray arrived some long-awaited reco, usually accompanied by six or seven cover notes, including all relevant signatures and the message ‘Proceed’.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko