In 1969 I was in my sixth year of school. At the time, primary education in Argentina ran for seven years. However, there was one school, the Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires, which admitted students after completing their sixth or the seventh elementary school year.

The CNBA was a very special secondary school: Argentina’s oldest, it had been founded by the Jesuits in 1660, when Buenos Aires had a population of only about 2000 people. A public school which offered free education since its inception, its alumni included four Presidents of Argentina and two Nobel laureates, as well as many members of government, politicians and several famous guerrilla leaders. Many foreign dignitaries had visited the school, including Albert Einstein, who at the height of his glory in 1925 had given a lecture there.

The Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires (which we just called ‘El Colegio’) was also part of the University of Buenos Aires, which meant that if you graduated from this high school, you were automatically admitted to the UBA. In 1969, the UBA was tough to get into, but so was getting admitted to El Colegio, which administered an entrance examination, with less than 10% admittance rate (no other public high school in Argentina had an entrance examination). The teachers at El Colegio were also professors at the UBA, a unique situation in Argentina.

I heard about El Colegio and set my heart on getting in. I saw it as a way to escape the elitist environment of St. Andrew’s, which increasingly made me feel uneasy. At the time, St. Andrew’s was a boys-only school and most of my friends lived in suburban houses with gardens and swimming pools. Most of my friends’ parents were immigrants like Paul and Lisl.

I wanted to integrate fully into Argentina and spend time in the centre of Buenos Aires. I also loved the adventure of going to school by a combination of bus, train and underground (a three-hour daily commute). Paul agreed for me to apply, because with his practical mind, he saw it as a great way to also secure entrance into the UBA. Had he known what kind of ‘education’ I would receive at El Colegio, and the people I would meet, he would have never given his consent, but in 1969 my desire to apply resonated with him and I received all the support I could, including evening classes with a private teacher.

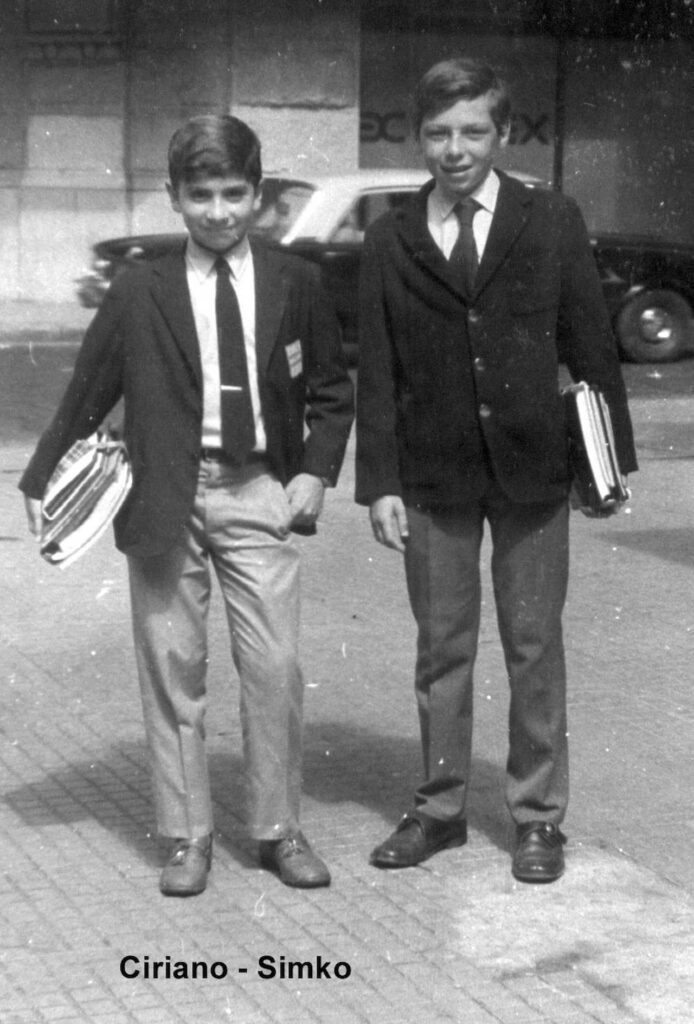

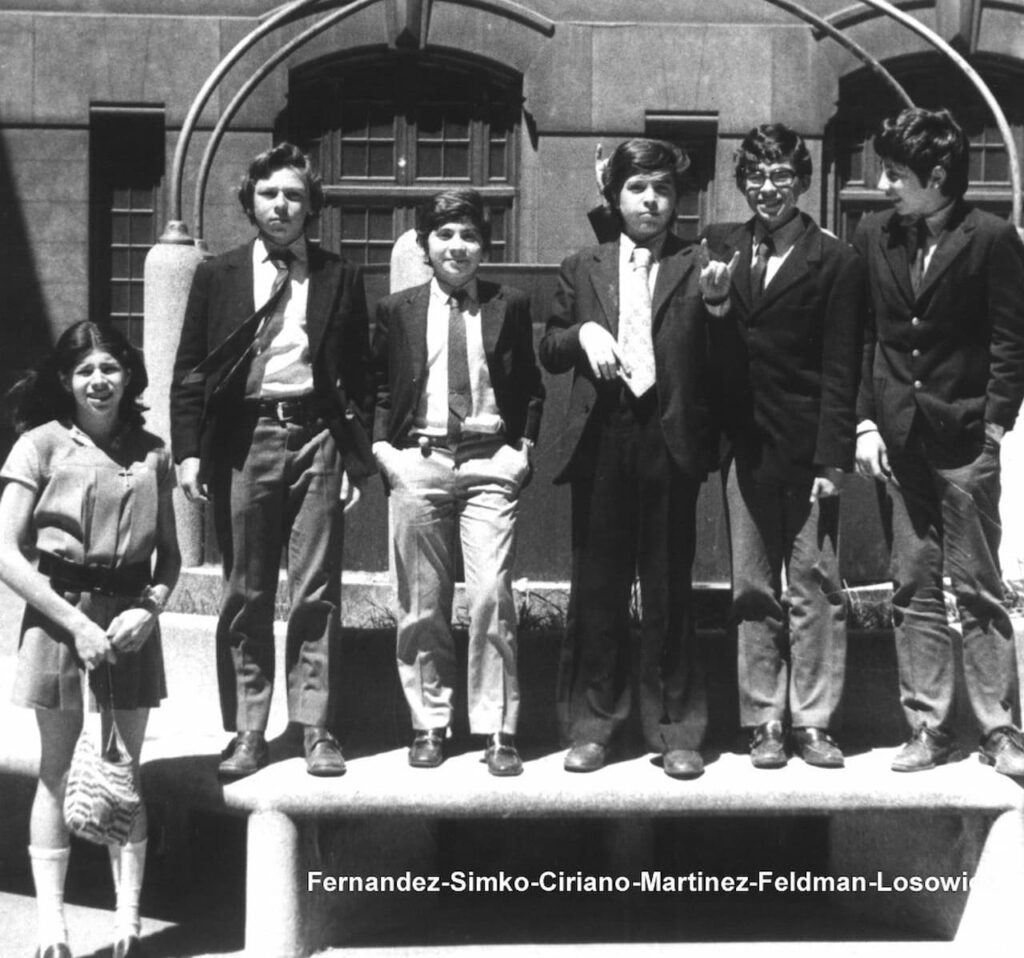

I was admitted to El Colegio, where I started in March 1970. At the time, the school’s schedule was organised around three ‘turnos’ (sessions): morning: from 8am till noon; afternoon: from 1pm till 5pm and evening: from 6pm until 10pm (this last schedule was reserved for students who had to work during the day, a not uncommon situation for adolescents at the time). I was enrolled in the afternoon (turno tarde), which allowed me sufficient time to arrive from San Isidro.

At the same time as I started my secondary education, and against the insistent advice of Annie, my parents decided to move me to a room in the back of the home, close to the swimming pool. Paul and Lisl presented the new room to me as a great way to have ‘my independence’, with a bedroom and a bathroom all to myself, ‘far away’ from my noisy younger siblings. In fact, however, Annie was right and it turned out to be a terrible decision. I felt lonely and isolated in this room, and was terrified to walk the short but very dark path from the main building to my room.

During my high school years, I suffered from recurrent insomnia, and often asked my parents if I could sleep on a mattress in the living room, in the main building. I also did everything I could to stay at friends’ homes during my adolescence. As on other occasions, my parents’ decision to move me to the back of the house, while well-meaning, did not take into account my specific needs. In hindsight, it would have been better to have kept me in a more cramped environment in the main building, than expose me to the solitude and anguish of an isolated room in the garden.

In 1970, when I entered El Colegio, uniforms were mandatory and the teaching was very conservative. It revolved around the classics (Latin, Mathematics and a bit of French and German—no English). History was taught every year, starting of course with Argentinian History, followed by Greek and Roman History in Year 2. In 1970, Argentina was run by a military junta. Accordingly, Argentinian History was primarily about the heroic feats of the Argentinian army. We had to learn the precise dates of every battle during the war of independence and know by heart the names of the victorious generals. We were taught what military manoeuvres had been particularly successful and how many soldiers the Spanish had lost in each confrontation with the victorious Argentinians.

Four years later, with the military no longer in power and with Argentina being ruled by a leftist government, we again had Argentinian History on the curriculum. But this time, it was mostly about the devastating psychological and sociological effects of colonialism, about the sneaky ways in which foreign powers had secured a footing in Argentina, and on how the indigenous populations had been wiped out. The former ‘great leaders’ of the Argentinian war of independence were now considered recalcitrant, backward, self-interested and bloody ‘mercenaries of international imperialism’, their military feats nothing but a carnage, and their administration of the nation, a cynical exploitation of the country’s vast resources, in order to strengthen the ‘bourgeois establishment’.

My early exposure to such different views of the same subject, alerted me to the importance of always looking at political and historical events from multiple angles. Today, I make sure that I read three or four different newspapers every day, with radically different orientations, in the hope of getting a balanced view of world events.

I finished my first year at El Colegio with very good marks, which meant that I didn’t have to take final examinations in December. It also meant that from the end of November till early March, I was on holidays. This was by far too long a time ‘to do nothing’, according to Paul. With his ever-practical mind, he decided that during December I should take a course to learn how to type. It was an incredibly embarrassing experience for me: I was the only boy in a class of about 40 young ladies. At the time, only future secretaries took a typing course, and no male in his right mind would have aspired to become a secretary. I would arrive at the last minute, sit in the back of the room and leave as soon as the bell rang. Of course, I never told my friends about my time at the Pittman Institute. But the typing course turned out to be hugely beneficial: I’m one of the very few in my generation who can type with 10 fingers and without looking at the keyboard. This would help me enormously during my university years and of course in the digital era.

The River

Pedro Simko

The River

Pedro Simko